Original Article - Year 2019 - Volume 34 -

Quality of life and aesthetic results after mastectomy and mammary reconstruction

Qualidade de vida e resultado estético após mastectomia e reconstrução mamária

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Due to the increased incidence of breast cancer, the demand for breast reconstruction has been increasing, along with concerns regarding the satisfaction and quality of life of the patients. Mastectomy can be a traumatic experience, especially when it is perceived as a mutilation, which can impact self-esteem and emotional stability. The BREAST-Q® questionnaire was internationally validated and formulated for the pre- and postoperative assessment of quality of life related to breast reconstruction. This study aimed to evaluate quality of life and aesthetic result satisfaction in patients who underwent breast reconstruction with implants by comparing the period after breast reconstruction with the period before.

Method: A retrospective longitudinal observational study was carried out by reviewing the charts of patients who underwent breast reconstruction using silicone or tissue expander implants from January 2014 to December 2016, in association with a cross-sectional study of the Breast-Q® questionnaire and an evaluation of aesthetic results based on photographic analysis before and after surgery.

Results: We selected 74 patients who underwent breast reconstruction with implants (79.7% with silicone prostheses and 20.3% with expanders); 95.94% of the reconstructions were immediate, and no particular laterality predominated. We obtained statistical significance in the domains of both breast satisfaction and physical well-being. Most cases were considered satisfactory by the external evaluator.

Conclusion: The patients' quality of life in the period after breast reconstruction with breast implants was superior to that in the period prior to the procedure.

Keywords: Breast neoplasms; Prostheses and implants; Quality of life; Surgery, Plastic; Mastectomy

RESUMO

Introdução: Em decorrência do aumento na incidência de câncer de mama, a procura pela reconstrução mamária vem crescendo, juntamente com a preocupação em relação à satisfação e à qualidade de vida das pacientes. Mastectomia pode ser vivenciada de modo traumático, sendo considerada mutilação, afetando autoestima e estabilidade emocional. O questionário BREAST-Q® foi validado internacionalmente e formulado para avaliação pré e pós-operatória da qualidade de vida relacionada à reconstrução mamária. O objetivo do estudo é avaliar a qualidade de vida e satisfação com o resultado estético das pacientes submetidas à reconstrução mamária com implantes, comparando o período anterior com o período posterior à reconstrução mamária.

Métodos: Realizado estudo observacional longitudinal retrospectivo por meio da revisão de prontuários de pacientes submetidas à reconstrução mamária com uso de implantes de silicone ou de expansor de tecido no período de janeiro de 2014 a dezembro de 2016, associado a estudo transversal por meio da aplicação do questionário Breast-Q® e avaliação do resultado estético após análise fotográfica pré e pós-operatória.

Resultados: Foram selecionadas 74 pacientes que foram submetidas à reconstrução mamária com implantes (79,7% com prótese de silicone e 20,3% com expansor); 95,94% das reconstruções foram imediatas e não houve predomínio quanto à lateralidade. Obtivemos significância estatística tanto no domínio satisfação com a mama quanto no domínio bem-estar físico. A maioria dos casos foram considerados satisfatórios pelo avaliador externo.

Conclusão: A qualidade de vida das pacientes no período posterior à reconstrução mamária com implantes mamários é superior em relação ao período anterior ao procedimento cirúrgico.

Palavras-chave: Neoplasias da mama; Implante de prótese; Qualidade de vida; Procedimentos cirúrgicos reconstrutivos; Mastectomia

INTRODUCTION

According to the National Cancer Institute, breast cancer is the second most common type of cancer among women in Brazil and worldwide, after non-melanoma skin cancer. Approximately 25% of all new cancer cases registered every year are breast cancers, and around 57,960 new cases of breast cancer registered in Brazil were expected in 2016. In 2013, 14,388 Brazilians, including 14,206 women, died from the disease1.

Owing to the increased incidence of breast cancer, the demand for breast reconstruction is also growing, along with concerns regarding the satisfaction and quality of life of patients.

Mastectomy, even when accompanied by immediate breast reconstruction, can be a traumatic experience for women and may be perceived as a mutilation, significantly impacting their self-esteem and emotional stability. In addition, after the surgery, patients may present with symptoms such as pain or discomfort in the breast area, changes in tactile sensation, and impaired upper limb functionality after dissection of the axillary lymph nodes, among others, all of which affect their quality of life2.

Given this scenario, breast reconstruction can be an important means of regaining a positive body image, re-establishing social engagement, and improving quality of life3.

The techniques used in breast reconstruction include the use of silicone prosthesis and tissue expanders and may be carried out immediately after mastectomy or may be delayed.

The silicone gel breast prosthesis was developed in 1961 by Cronin, Gerow, and Dow Corning Corp. and introduced in 1963, significantly advancing the field of breast reconstruction. In France, Arion introduced the first tissue expander in 1965, but it was not until 1982 that Radovan described its use in breast reconstruction. In 1984, Becker developed a definitive tissue expander. Techniques that have developed in tandem with the use of these alloplastic materials have improved patients’ quality of life, reducing the impact of perceived mutilation and surgical time, with the advantages of a shorter hospital stay, absence of donor area, and reduced risk of complications4,5.

The most effective way to evaluate quality of life is by means of validated questionnaires that focus on the treatment in question6,7. The BREAST-Q® questionnaire has been validated and specifically developed to assess pre- and postoperative quality of life related to breast reconstruction7,8.

OBJECTIVE

The main objective of this study was to evaluate patients’ quality of life and satisfaction with the aesthetic result following breast reconstruction with implants via comparison between the pre-reconstruction and post-reconstruction periods.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This was a retrospective longitudinal observational study conducted by reviewing the medical records of patients who underwent breast reconstruction using silicone implants or tissue expanders from January 2014 to December 2016, in association with a cross-sectional study of the application of the BREAST-Q® questionnaire and evaluation of aesthetic results based on an analysis of pre-and postoperative photographs.

The research project followed the legal procedures determined by resolution 196/96 of the National Health Council regarding research involving human beings and was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

All surgeries were performed by the same plastic surgeon in 5 hospitals located in the city of Brasilia (DF).

The variables evaluated were age, body mass index (BMI), comorbidities, type of breast reconstruction performed, the result of the histopathological study of lesion biopsy, laterality, time of breast reconstruction (immediate or delayed), symmetrization, preservation of the nipple-areola complex (NAC) upon mastectomy, postoperative complications, chemotherapy (CT), and radiotherapy (RT), as well as whether all stages of breast reconstruction were completed.

The inclusion criteria set for the study were:

Patients undergoing total mastectomy due to breast cancer or for

prophylactic reasons;

Patients undergoing breast reconstruction by techniques involving a

breast prosthesis or tissue expander;

Patients who agreed to the free and informed consent terms,

authorizing the use of their records and their photographs for

scientific purposes.

The exclusion criteria were:

Questionnaire for assessing quality of life – BREAST-Q®

Quality of life of patients was evaluated by the BREAST-Q®, a questionnaire validated internationally for the development of scales to assess quality of life related to breast reconstruction from the patient’s perspective6,7. It was developed based on the guidelines of the FDA (U.S. Food and Drug Administration/Guidance and Compliance Regulatory Information). The questionnaire is composed of 4 independent modules (reductive mammoplasty, breast augmentation, breast reconstruction, and mastectomy). Each of the modules includes a core of independent scales that assess 6 domains (satisfaction with breasts, satisfaction with outcome, psychosocial well-being, sexual well-being, physical well-being, and satisfaction with care).

The patients’ responses to the items in each domain are transformed by the Q-Score® scoring software to yield a total score (for each scale) ranging from 0 to 100. For all BREAST- Q® scales, a higher score indicates greater satisfaction or a better quality of life7,8.

The questionnaire was translated into Portuguese without any change in the meaning of any sentence. Two versions of the questionnaire were used, one specific to the preoperative period and one for the postoperative period. For the preoperative questionnaire, 4 domains were used (satisfaction with breasts, psychosocial well-being, physical well-being, and sexual well-being). For the postoperative questionnaire, 5 domains were used (satisfaction with breasts, satisfaction with outcome, psychosocial well-being, sexual well-being, and physical well-being), plus one subdomain (satisfaction with nipple).

Satisfaction and aesthetic result

A medical assessment of the aesthetic result was performed after analyzing pre- and postoperative photographs obtained from the medical records. The surgeon’s satisfaction with the results achieved was classified as unsatisfactory in cases rated as poor or regular or satisfactory in cases rated as good or very good. Patient satisfaction was assessed by the BREAST-Q® questionnaire.

Surgical technique

The same surgical technique was applied to both procedures: reconstruction using either a prosthesis or an extender. The choice between the two techniques was always made at the time of surgery when the pliancy of the muscle was tested through the placement of molds. In cases where it was not possible to achieve a proper size with direct implantation of the prosthesis, a tissue expander was used.

Initially, the patient was subjected to mastectomy under general anesthesia by a mastology team and the weight of the part removed was assessed. Thereafter, the plastic surgery team took charge, preparing a submuscular pocket after infiltration with 0.9% saline solution and epinephrine (1:300,000), using the greater pectoral muscle, rectus abdominis, and the fascia of the anterior serratus (when possible) or the muscle itself. Rigorous hemostasis was performed followed by testing with molds and implant placement, either a prosthesis or expander. Finally, the surgical pocket was closed, a Portovac drain was placed, and the skin flaps were adjusted followed by sutures.

RESULTS

A total of 74 patients who underwent breast reconstruction with implants were selected: 59 (79.72%) with a silicone prosthesis and 15 (20.27%) with an expander (Table 1). The age of the patients ranged from 24 to 81 years, with an average of 55 years and a median of 54 years. The BMI ranged from 17.95 to 36.98, with an average of 24.50.

| Demographic data - breast reconstruction | ||

|---|---|---|

| Silicone prosthesis | 59 (79.72%) | |

| Expander | 15 (20.27%) | |

| Immediate | 71 (95.94%) | |

| Late | 03 (4.05%) | |

| Unilateral | 37 (50%) | |

| Bilateral | 37 (50%) | |

| Nac preservation | 30 (40.54%) | |

| Symmetrization | 48 (64.86%) | |

| CT | 45 (60.81%) | |

| ADJ | 24 (53.33%) | |

| NEO | 21 (46.67%) | |

| RT | 24 (32.43%) | |

| Total = 74 (100%) | ||

Among the 74 breast reconstructions, 71 (95.94%) were performed at the same time as mastectomy and classified as immediate breast reconstruction. Only 3 (4.05%) reconstructions were late reconstructions. In terms of laterality, 50% were unilateral and 50% were bilateral (Table 1).

In 30 (40.54%) of the breast reconstructions performed, the NAC was spared. In addition, 48 (64.86%) patients underwent a second operation for breast symmetrization (Table 1).

Of the 74 patients undergoing breast reconstruction, 45 (60.81%) received complementary CT after mastectomy, 24 (53.33%) underwent adjuvant CT (ADJ), and 21 (46.67%) underwent neoadjuvant CT (NEO). Twenty-nine (39.18%) patients did not undergo any type of CT. RT was required in 24 (32.43%) patients (Table 1).

In terms of comorbidities, 17 (22.97%) of the patients who underwent breast reconstruction had none. In contrast, 16 (21.62%) patients were hypertensive, 15 (20.27%) presented with dyslipidemia, 13 (17.57%) had hypothyroidism, 8 (10.81%) reported being treated for depression, 6 (8.11%) had diabetes type II, 3 (4.05%) had arrhythmia and/or other cardiac disorders, 1 (1.35%) had multiple myeloma, 1 (1.35%) had thrombophilia, and 1 (1.35%) was a carrier of a genetic mutation for thrombosis. In addition, 5 (6.76%) patients were smokers and 15 (20.27%) reported being ex-smokers. Many patients had more than one comorbidity.

With regard to surgical complications after breast reconstruction surgery, 33 (44.59%) patients did not experience any type of complication. However, there were 14 (18.92%) cases of seroma, 7 (9.46%) cases of slight necrosis in the NAC region, 6 (8.11%) cases of slight dehiscence in the T region, 5 (6.76%) cases of hematoma, 3 (4.05%) cases of breast asymmetry, and 3 (4.05%) cases of capsular contracture. Three other complications were observed, including infection (2 cases) and late venous thrombosis. Some patients had more than one complication (Table 2).

| Post-operative complications | |

|---|---|

| Seroma | 14 (18.92%) |

| Slight nac necrosis | 07 (9.46%) |

| Dehiscence | 06 (8.11%) |

| Hematomas | 05 (6.76%) |

| Asymmetry | 03 (4.05%) |

| Capsular contracture | 03 (4.05%) |

| Others | 03 (4.05%) |

| Total = 74 (100%) | |

Of the 74 patients selected, 52 (70.27%) answered the pre-reconstruction questionnaire, while 48 (64.86%) answered the post-reconstruction questionnaire. The responses of 4 patients who did not answer the post-reconstruction questionnaire were excluded from the study. In addition, the responses of 3 more patients were excluded because they were incomplete, yielding a total of 45 (60.81%) patients with responses. Statistical analysis of the pre- and post-reconstruction responses was performed.

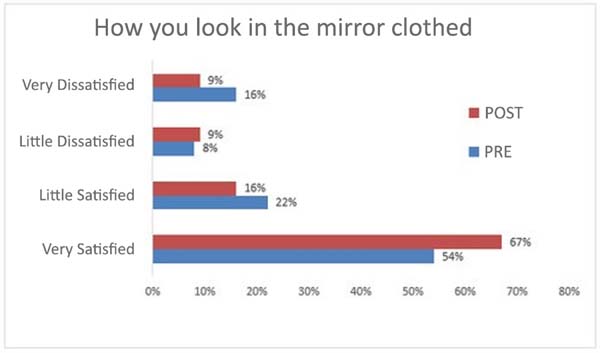

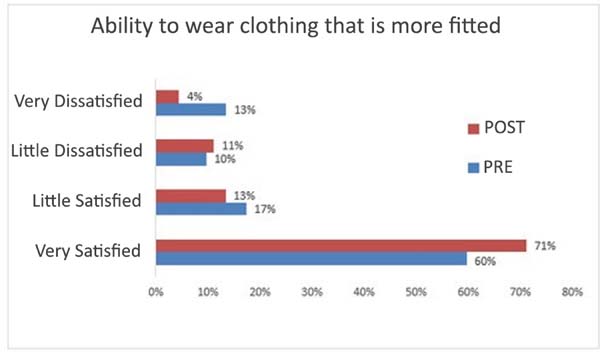

In terms of the breast satisfaction domain, statistical significance in the comparison of the pre- and post-reconstruction responses was found for the following two questions: “How you look in the mirror clothed?” and “Being able to wear clothing that is more fitted?”, with p = 0.00121 and p = 0.0249, respectively (Figures 1 and 2).

Tables 3, 4, and 5 show the number of answers, in percentages, for each question in the pre- and post-reconstruction questionnaires. In addition, they display the p values obtained by statistical analysis. Table 3 refers to the psychosocial well-being domain, Table 4 refers to the physical well-being domain, and Table 5 refers to the sexual well-being domain. Statistical significance was shown for 4 questions in the physical well-being domain, as shown in Table 4, but not for the psychosocial well-being and sexual well-being domains.

| Confident in social settings | ||||

| All of the time | 56 | 54.55 | 0.9286 | |

| Most of the time | 30 | 29.55 | ||

| Some of the time | 6 | 9.09 | ||

| A little of the time | 6 | 4.55 | ||

| None of the time | 2 | 2.27 | ||

| Able to do things that you want to do | ||||

| All of the time | 41.18 | 44.44 | 0.6620 | |

| Most of the time | 39.22 | 42.22 | ||

| Some of the time | 9.80 | 8.89 | ||

| A little of the time | 5.88 | 2.22 | ||

| None of the time | 3.92 | 2.22 | ||

| Emotionally healthy | ||||

| All of the time | 31.37 | 46.67 | 0.1755 | |

| Most of the time | 50.98 | 35.56 | ||

| Some of the time | 7.84 | 8.89 | ||

| A little of the time | 5.88 | 6.67 | ||

| None of the time | 3.92 | 2.22 | ||

| Of equal worth to other women | ||||

| All of the time | 49.02 | 50 | 0.1442 | |

| Most of the time | 29.41 | 31.82 | ||

| Some of the time | 15.69 | 11.36 | ||

| A little of the time | 0 | 4.45 | ||

| None of the time | 5.88 | 2.27 | ||

| Self-assured | ||||

| All of the time | 37.25 | 38.64 | 0.4324 | |

| Most of the time | 41.18 | 45.45 | ||

| Some of the time | 13.73 | 9.09 | ||

| A little of the time | 1.96 | 4.55 | ||

| None of the time | 5.88 | 2.27 | ||

| Feminine in clothing | ||||

| All of the time | 49.02 | 47.73 | 0.1178 | |

| Most of the time | 29.41 | 36.36 | ||

| Some of the time | 13.73 | 6.82 | ||

| A little of the time | 1.96 | 6.82 | ||

| None of the time | 5.88 | 2.27 | ||

| Accepting own body | ||||

| All of the time | 37.25 | 40.91 | 0.6593 | |

| Most of the time | 41.18 | 40.91 | ||

| Some of the time | 11.76 | 9.09 | ||

| A little of the time | 1.96 | 4.55 | ||

| None of the time | 7.84 | 4.55 | ||

| Normal | ||||

| All of the time | 39.22 | 46.67 | 0.5750 | |

| Most of the time | 43.14 | 35.56 | ||

| Some of the time | 7.84 | 11.11 | ||

| A little of the time | 1.96 | 2.22 | ||

| None of the time | 7.84 | 4.44 | ||

| Equal to other women | ||||

| All of the time | 39.22 | 47.73 | 0.3179 | |

| Most of the time | 39.22 | 29.55 | ||

| Some of the time | 11.76 | 13.64 | ||

| A little of the time | 3.92 | 6.82 | ||

| None of the time | 5.88 | 2.27 | ||

| Attractive | ||||

| All of the time | 25.49 | 38.64 | 0.0662 | |

| Most of the time | 37.25 | 27.27 | ||

| Some of the time | 15.69 | 22.73 | ||

| A little of the time | 13.73 | 6.82 | ||

| None of the time | 7.84 | 4.55 | ||

| Physical well-being | Pre (%) | Post (%) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neck pain | ||||

| All of the time | 2.08 | 0.00 | 0.1347 | |

| Most of the time | 6.25 | 4.55 | ||

| Some of the time | 14.58 | 27.27 | ||

| A little of the time | 10.42 | 11.36 | ||

| None of the time | 66.67 | 56.82 | ||

| Back pain | ||||

| All of the time | 2.08 | 2.27 | 0.3240 | |

| Most of the time | 12.50 | 9.09 | ||

| Some of the time | 20.83 | 27.27 | ||

| A little of the time | 16.67 | 25 | ||

| None of the time | 47.92 | 36.36 | ||

| Shoulder pain | ||||

| All of the time | 2.08 | 0.00 | 0.2905 | |

| Most of the time | 10.42 | 6.82 | ||

| Some of the time | 14.68 | 22.73 | ||

| A little of the time | 14.58 | 11.36 | ||

| None of the time | 58.33 | 59.09 | ||

| Pain in arms | ||||

| All of the time | 4.17 | 0.00 | 0.0396* | |

| Most of the time | 4.17 | 2.27 | ||

| Some of the time | 16.67 | 20.45 | ||

| A little of the time | 37.50 | 25 | ||

| None of the time | 37.50 | 52.27* | ||

| Pain in ribs | ||||

| All of the time | 2.08 | 0.00 | 0.0007* | |

| Most of the time | 14.58* | 2.27 | ||

| Some of the time | 20.83* | 11.36 | ||

| A little of the time | 18.75 | 18.18 | ||

| None of the time | 43.75 | 68.18* | ||

| Muscle pain | ||||

| All of the time | 6.38 | 2.27 | 0.5263 | |

| Most of the time | 4.26 | 6.82 | ||

| Some of the time | 19.15 | 15.91 | ||

| A little of the time | 17.02 | 15.91 | ||

| None of the time | 53.19 | 59.09 | ||

| Difficulty lifting or moving your arms | ||||

| All of the time | 6.38 | 2.27 | 0.1253 | |

| Most of the time | 4.26 | 6.82 | ||

| Some of the time | 8.51 | 4.55 | ||

| A little of the time | 31.91 | 22.73 | ||

| None of the time | 48.94 | 63.64 | ||

| Difficulty sleeping due to discomfort in the breast area | ||||

| All of the time | 10.64* | 2.27 | 0.0257* | |

| Most of the time | 6.38 | 15.91* | ||

| Some of the time | 21.28 | 22.73 | ||

| A little of the time | 25.53 | 18.18 | ||

| None of the time | 36.17 | 40.91 | ||

| Chest pain | ||||

| All of the time | 6.38 | 6.82 | 0.9500 | |

| Most of the time | 6.38 | 4.55 | ||

| Some of the time | 12.77 | 11.36 | ||

| A little of the time | 23.40 | 27.27 | ||

| None of the time | 51.06 | 50 | ||

| Tightness in breast area | ||||

| All of the time | 6.38 | 7.32 | 0.7006 | |

| Most of the time | 6.38 | 7.32 | ||

| Some of the time | 17.02 | 14.63 | ||

| A little of the time | 21.28 | 29.27 | ||

| None of the time | 48.94 | 41.46 | ||

| Pulling in breast area | ||||

| All of the time | 6.38 | 6.82 | 0.2634 | |

| Most of the time | 4.26 | 4.55 | ||

| Some of the time | 4.26 | 11.36 | ||

| A little of the time | 19.15 | 11.36 | ||

| None of the time | 65.96 | 65.91 | ||

| Pain when breast are touched | ||||

| All of the time | 8.70 | 4.55 | 0.1271 | |

| Most of the time | 13.04 | 13.64 | ||

| Some of the time | 19.57 | 27.27 | ||

| A little of the time | 39.96 | 25 | ||

| None of the time | 21.74 | 29.55 | ||

| Sensitivity in breast area | ||||

| All of the time | 4.26* | 0.00 | 0.0121* | |

| Most of the time | 0.00 | 6.82* | ||

| Some of the time | 23.40 | 22.73 | ||

| A little of the time | 23.40 | 15.91 | ||

| None of the time | 48.94 | 54.55 | ||

| Sharp pain in breast area | ||||

| All of the time | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.3886 | |

| Most of the time | 2.13 | 2.27 | ||

| Some of the time | 4.26 | 6.82 | ||

| A little of the time | 2.13 | 4.55 | ||

| None of the time | 91.49 | 86.36 | ||

| Unbearable pain in breast area | ||||

| All of the time | 2.13 | 2.27 | 0.1931 | |

| Most of the time | 0.00 | 4.55 | ||

| Some of the time | 10.64 | 11.36 | ||

| A little of the time | 34.04 | 25 | ||

| None of the time | 53.19 | 56.82 | ||

| Throbbing in breast area | ||||

| Tempo todo | 2.13 | 0.00 | 0.1274 | |

| Maioria das vezes | 4.26 | 0.00 | ||

| Algumas vezes | 6.38 | 9.09 | ||

| Poucas vezes | 21.28 | 25 | ||

| Nunca | 65.96 | 65.91 | ||

| Sexual well-being | Pre (%) | Post (%) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sexually attractive in your clothes | ||||

| All of the time | 21.28 | 24.44 | 0.1683 | |

| Most of the time | 40.43 | 35.56 | ||

| Some of the time | 10.64 | 15.56 | ||

| A little of the time | 17.02 | 6.67 | ||

| None of the time | 4.26 | 6.67 | ||

| Not applicable | 6.38 | 11.11 | ||

| Comfortable/at ease during sexual activity | ||||

| All of the time | 25.73 | 20 | 0.9291 | |

| Most of the time | 25.73 | 28.89 | ||

| Some of the time | 12.77 | 15.56 | ||

| A little of the time | 10.64 | 8.89 | ||

| None of the time | 4.26 | 4.44 | ||

| Not applicable | 21.28 | 22.22 | ||

| Confident sexually | ||||

| All of the time | 23.40 | 20 | 0.9907 | |

| Most of the time | 29.79 | 28.89 | ||

| Some of the time | 14.89 | 15.56 | ||

| A little of the time | 8.51 | 8.89 | ||

| None of the time | 4.26 | 4.44 | ||

| Not applicable | 19.15 | 22.22 | ||

| Satisfied with your sex life | ||||

| All of the time | 23.40 | 20.45 | 0.1864 | |

| Most of the time | 25.53 | 31.82 | ||

| Some of the time | 21.28 | 13.64 | ||

| A little of the time | 2.13 | 9.09 | ||

| None of the time | 4.26 | 2.27 | ||

| Not applicable | 23.40 | 22.73 | ||

| Confident sexually when unclothed | ||||

| All of the time | 23.40 | 20.45 | 0.7145 | |

| Most of the time | 23.40 | 31.82 | ||

| Some of the time | 10.64 | 9.09 | ||

| A little of the time | 14.89 | 13.64 | ||

| None of the time | 4.26 | 6.82 | ||

| Not applicable | 23.40 | 18.18 | ||

| Attractive sexually when unclothed | ||||

| All of the time | 17.02 | 20 | 0.9097 | |

| Most of the time | 29.79 | 31.11 | ||

| Some of the time | 14.89 | 11.11 | ||

| A little of the time | 17.02 | 13.33 | ||

| None of the time | 6.38 | 6.67 | ||

| Not applicable | 14.89 | 17.78 | ||

Table 6 presents the descriptive statistics of the results obtained from the Q-Score®, as well as the statistical analysis comparing the responses of patients for the pre-reconstruction period with those for the post-reconstruction period.

| Groups | Variation | Average | Standard Deviation | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Satisfaction with breasts | Pre | 0-100 | 73.946 | 27.0606 | 0.932 |

| Post | 0-100 | 74.432 | 24.0865 | ||

| Psychosocial well-being | Pre | 0-100 | 69.4 | 22.4794 | 0.005 |

| Post | 0-100 | 82.568 | 19.531 | ||

| Physical well-being | Pre | 0-100 | 67.325 | 16.7491 | 0.215 |

| Post | 0-100 | 71.659 | 15.0255 | ||

| Sexual well-being | Pre | 0-100 | 61.056 | 22.0233 | 0.482 |

| Post | 0-100 | 64.795 | 23.7023 |

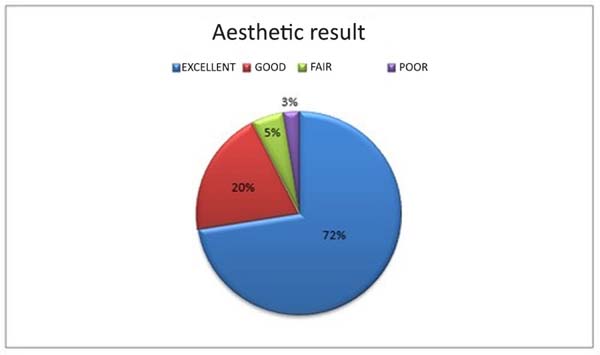

Among 74 patients, breast reconstruction with symmetrization and reconstruction of the NAC was achieved in 40 (54.05%) patients, whose cases were analyzed by an experienced plastic surgeon without correlation with the proposed work. The majority of cases were rated as excellent by the external evaluator, and only 1 case was rated as poor. In total, 37 (92.5%) cases were considered satisfactory and 3 (7.5%) unsatisfactory. (Figure 3)

DISCUSSION

Breast cancer is the most prevalent cancer in women and often leads to a significant decrease in the ability to have a normal life1. The beneficial effects of breast reconstruction on quality of life and psychosocial well-being are well documented. In a variety of studies, women who underwent reconstruction after mastectomy showed improvements in self-image, sexuality, and decreased rates of depression9-12.

Plastic surgery is a specialty in which results are evaluated mainly by patient satisfaction13. Therefore, studies with the main objective of evaluating quality of life and aesthetic outcome satisfaction in patients undergoing breast reconstruction are critical.

Innumerable breast reconstruction techniques are available, and the selection of which technique will be used in each patient is influenced by several factors, including BMI, comorbidities, presence of donor areas for autologous reconstruction, patient preference, expectation as to the results, lifestyle factors, staging, need for radiotherapy, type of mastectomy, laterality (unilateral or bilateral), and others14.

Breast reconstructions with prostheses and/or tissue expanders are widely performed throughout the world and continue to be an excellent alternative for patients with contraindications for autologous reconstruction, those who cannot be subjected to extensive surgery, and those not wanting a prolonged postoperative recovery or a scar in the donor area15.

A total of 74 women between 24 and 81 years of age were selected for the present study. According to the National Cancer Institute (INCA), breast tumors in women aged less than 35 years are relatively rare, and the incidence rises progressively from that age onward, especially after 50 years of age16. In our study, with the exception of one 24-year-old patient, all the patients were aged over 35 years.

The mean BMI presented in this study was 24.5 kg/m2, which is higher than that in previously published data that indicated an average BMI of 22.0 kg/m2 in breast reconstruction patients17.

In our study, the complication rate was 55.4%, with the majority being slight seroma formation (18.92%) and slight necrosis in the NAC region (9.46%). The overall incidence of any type of complication in this study was comparable with published studies that reported a complication rate ranging from 4% to 58%18-22.

Although the use of implants facilitates faster and simpler breast reconstructions, it tends to be associated with specific complications, such as capsular contracture. The percentage of verified capsular contracture in this study was 4.05%, which is lower than the 10% to 56% rate reported in other studies18-22.

Bilateral reconstructions have been gaining ground in recent years, either for therapeutic reasons due to the characteristics of the tumor, for indications of prophylactic mastectomy due to genetic alterations that lead to a significant increase in the risk of cancer, or even by the decision of the patient to undergo prophylactic contralateral mastectomy.

According to some studies, there is a positive influence of bilateral breast reconstruction on breast satisfaction owing to the symmetry that is more easily achieved and the fact that concern about the risk of cancer in the contralateral breast can be reduced10. In our study, half of the cases underwent bilateral reconstruction and the other half underwent unilateral. Most of the cases considered optimal included bilateral reconstructions. However, in the 3 cases with asymmetry as a complication in our study, the breast reconstruction was bilateral.

The majority of patients underwent immediate reconstruction (95.94%). According to previous reports, the majority of women opt for this form of breast reconstruction in an attempt to lessen the negative feelings triggered by the disease and its treatment, as well as to improve self-esteem, resolve the lack of a breast, and facilitate greater freedom in clothing options. After mastectomy, the absence of the breast alters a woman’s body image, potentially generating a sensation of mutilation and the loss of femininity and sensuality23. There are published reports demonstrating better social interaction, higher levels of professional satisfaction and fulfillment, and a lower frequency of depression at one year after surgery among women who underwent mastectomy associated with immediate reconstruction24,25.

The treatment of breast cancer is guided by the characteristics of the tumor, and radiotherapy and chemotherapy are complementary to mastectomy. While radiotherapy decreases the incidence of local recurrence and improves the survival of patients, it can affect breast symmetry, impair aesthetics, and decrease quality of life. In previous studies on patients who underwent breast reconstruction with implants and radiotherapy, radiotherapy was found to negatively impact their quality of life and breast satisfaction26,27. Of the 74 patients undergoing breast reconstruction in our study, 45 (60.81%) underwent chemotherapy (CT) and 24 (32.43%) underwent radiotherapy. Of the 29 cases considered optimal by the external evaluator, 9 (31.033%) underwent radiotherapy. Of the 8 cases considered good, 3 (37.5%) received radiotherapy. Moreover, of the 3 cases considered fair and poor, 2 (66.67%) received radiotherapy.

Factors related to quality of life and aesthetic outcomes of breast reconstructions performed with implants were evaluated by means of the BREAST-Q® questionnaire, which was developed and validated as a specific measure of quality of life.

In 2016, Kuroda et al28. used the BREAST-Q® to evaluate aesthetic results and quality of life outcomes in Brazilian patients who underwent immediate breast reconstruction using implants and demonstrated that breast reconstruction leads to satisfactory quality of life outcomes.

In the present study, we observed that breast reconstruction, despite the complications inherent to the procedure, facilitates enhanced quality of life and patient satisfaction. In the domains of satisfaction with breasts, psychosocial well-being, physical well-being, and sexual well-being, the scores were higher scores in the postoperative questionnaire than in the preoperative questionnaire quantified by Q-Score®. In particular, a significant result in the domain of “psychosocial well-being” was found (p = 0.005).

In a 2014 retrospective study, Ng et al29. evaluated 143 mastectomized patients (79 with reconstruction and 64 without) using the BREAST-Q® questionnaire. The reconstruction group showed higher BREAST-Q® scores in the domains of “satisfaction with breasts”, “psychosocial well-being”, and “sexual well-being” and also showed improved self-esteem, increased clothing options, and a greater sense of overcoming the cancer.

In 2013, Zhong et al. evaluated 29 mastectomized patients before and after breast reconstruction with the BREAST-Q® questionnaire and observed improvements in satisfaction with breasts and psychosocial and sexual well-being.

In terms of the statistical analysis comparing the responses of the two groups for each question, statistical significance was found for the following 6 questions: “How you look in the mirror clothed?” (p = 0.00121); “Being able to wear clothing that is more fitted?” (p = 0.0249); “How often do you feel pain in the arms?” (p = 0.0396); “How often do you feel pain in the ribs?” (p = 0.0007); “How often do you have difficulty sleeping due to discomfort in the breast area?” (p = 0.0257); and “How often do you feel sharp pain in the breasts?” (p = 0.0121).

It is interesting to highlight the positive responses to the questions in the physical well-being domain, as more physical symptom complaints were expected after the surgical procedure. In 2013, Eltahir et al30. assessed the quality of life of women following breast reconstruction in comparison with those of patients who underwent mastectomy, using the BREAST-Q® questionnaire, and observed that women showed less pain and fewer limitations after reconstruction (p = 0.007).

CONCLUSION

The quality of life of patients in the period after breast reconstruction with silicone prostheses or tissue expanders was higher than that in the pre-reconstruction period.

Despite the feeling of mutilation and trauma incurred by the mastectomy procedure, breast reconstruction, when carefully executed by a well-trained and specialized team, can yield excellent aesthetic results.

COLLABORATIONS

|

MCC |

Analysis and/or data interpretation, final manuscript approval, realization of operations and/or trials. |

|

ACC |

Conception and design study, writing - review & editing. |

|

CADCF |

Analysis and/or data interpretation, final manuscript approval, realization of operations and/or trials. |

|

GCS |

Conception and design study, writing - review & editing. |

|

LDPB |

Conception and design study, writing - review & editing. |

|

RCSD |

Conception and design study, writing - review & editing. |

|

FTV |

Formal analysis. |

|

JCD |

Final manuscript approval. |

REFERENCES

1. Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Instituto Nacional de Câncer José Alencar Gomes da Silva. Estimativa 2016: Incidência de Câncer no Brasil. Rio de Janeiro: INCA; 2015.

2. Santos DB, Vieira EM. Imagem corporal de mulheres com câncer de mama: uma revisão sistemática da literatura. Ciênc Saúde Coletiva. 2011;16(5):2511-22. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/S1413-81232011000500021

3. Serletti JM, Fosnot J, Nelson JA, Disa JJ, Bucky LP. Breast reconstruction after breast cancer. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;127(6):124e-35e. PMID: 21617423

4. Rietjens M, Urban CA. Cirurgia da mama estética e reconstrutiva. Rio de Janeiro: Revinter; 2007.

5. Saldanha OR, Urdaneta FV, Llaverias F, Saldanha Filho OR, Saldanha CB. Reconstrução de mama com retalho excedente de abdominoplastia reversa. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2014;29(2):297-302.

6. Cano SJ, Klassen A, Pusic AL. The science behind quality-of-life measurement: a primer for plastic surgeons. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;123(3):98e-106e. PMID: 19319025

7. Pusic AL, Klassen AF, Scott AM, Klok JA, Cordeiro PG, Cano SJ. Development of a new patient-reported outcome measure for breast surgery: the BREAST-Q. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124(2):345-53. PMID: 19644246 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181aee807

8. Pusic A, Cordeiro PG. An accelerated approach to tissue expansion for breast reconstruction: experience with intraoperative and rapid postoperative expansion in 370 reconstructions. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;111(6):1871-5. PMID: 12711946 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/01.PRS.0000056871.83116.19

9. Al-Ghazal SK, Fallowfield L, Blamey RW. Comparison of psychological aspects and patient satisfaction following breast conserving surgery, simple mastectomy and breast reconstruction. Eur J Cancer. 2000;36(15):1938-43. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0959-8049(00)00197-0

10. Andrade WN, Baxter N, Semple JL. Clinical determinants of patient satisfaction with breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;107(1):46-54. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/00006534-200101000-00008

11. Eltahir Y, Werners LL, Dreise MM, van Emmichoven IA, Jansen L, Werker PM, et al. Quality-of-life outcomes between mastectomy alone and breast reconstruction: comparison of patient-reported BREAST-Q and other health-related quality-of-life measures. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;132(2):201e-209e. PMID: 23897347

12. Veiga DF, Veiga-Filho J, Ribeiro LM, Archangelo I Jr, Balbino PF, Caetano LV, et al. Quality-of-life and self-esteem outcomes after oncoplastic breast-conserving surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;125(3):811-7. PMID: 20195109 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181ccdac5

13. Chen CM, Cano SJ, Klassen AF, King T, McCarthy C, Cordeiro PG, et al. Measuring quality of life in oncologic breast surgery: a systematic review of patient-reported outcome measures. Breast J. 2010;16(6):587-97. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1524-4741.2010.00983.x

14. Nahabedian MY. Factors to consider in breast reconstruction. Womens Health (Lond). 2015;11(3):325-42. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2217/WHE.14.85

15. Aguiar IC, Veiga DF, Marques TF, Novo NF, Sabino Neto M, Ferreira LM. Patient-reported outcomes measured by BREAST-Q after implant-based breast reconstruction: A cross-sectional controlled study in Brazilian patients. Breast. 2017;31:22-5. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.breast.2016.10.008

16. Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Instituto Nacional de Câncer. Câncer de mama. INCA. [acesso 2017 Jun 28]. Disponível em: http://www2.inca.gov.br/wps/wcm/connect/tiposdecancer/site/home/mama

17. Weichman KE, Broer PN, Thanik VD, Wilson SC, Tanna N, Levine JP, et al. Patient-Reported Satisfaction and Quality of Life following Breast Reconstruction in Thin Patients: A Comparison between Microsurgical and Prosthetic Implant Recipients. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;136(2):213-20. PMID: 25909301 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0000000000001418

18. Hudson DA, Skoll PJ. Complete one-stage, immediate breast reconstruction with prosthetic material in patients with large or ptotic breasts. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;110(2):487-93. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/00006534-200208000-00018

19. Baroudi R, Ferreira CA. Seroma: how to avoid it and how to treat it. Aesthet Surg J. 1998;18(6):439-41. PMID: 19328174 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S1090-820X(98)70073-1

20. Sigurdson L, Lalonde DH. MOC-PSSM CME article: Breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;121(1 Suppl):1-12. PMID: 18182962

21. Christensen BO, Overgaard J, Kettner LO, Damsgaard TE. Long-term evaluation of postmastectomy breast reconstruction. Acta Oncol. 2011;50(7):1053-61. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3109/0284186X.2011.584554

22. Lejour M, Jabri M, Deraemaecker R. Analysis of long-term results of 326 breast reconstructions. Clin Plast Surg. 1988;15(4):689-701.

23. Oliveira RR, Morais SS, Sarian LO. Efeitos da reconstrução mamária imediata sobre a qualidade de vida de mulheres mastectomizadas. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet. 2010;32(12):602-8. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/S0100-72032010001200007

24. Tkachenko GA, Arslanov KhS, Iakovlev VA, Blokhin SN, Shestopalova IM, Portnoi SM, et al. Long-term impact of breast reconstruction on quality of life among breast cancer patients. Vopr Onkol. 2008;54(6):724-8. PMID: 19241847

25. Roth RS, Lowery JC, Davis J, Wilkins EG. Quality of life and affective distress in women seeking immediate versus delayed breast reconstruction after mastectomy for breast cancer. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;116(4):993-1002. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/01.prs.0000178395.19992.ca

26. Albornoz CR, Matros E, McCarthy CM, Klassen A, Cano SJ, Alderman AK, et al. Implant breast reconstruction and radiation: a multicenter analysis of long-term health-related quality of life and satisfaction. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21(7):2159-64. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-014-3483-2

27. Chen SA, Hiley C, Nickleach D, Petsuksiri J, Andic F, Riesterer O, et al. Breast reconstruction and post-mastectomy radiation practice. Radiat Oncol. 2013;8:45. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-717X-8-45

28. Kuroda F, Urban C, Zucca-Matthes G, de Oliveira VM, Arana GH, Iera M, et al. Evaluation of Aesthetic and Quality-of-Life Results after Immediate Breast Reconstruction with Definitive Form-Stable Anatomical Implants. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016;137(2):278e-86e.

29. Ng SK, Hare RM, Kuang RJ, Smith KM, Brown BJ, Hunter-Smith DJ. Breast Reconstruction Post Mastectomy: Patient Satisfaction and Decision Making. Ann Plast Surg. 2016;76(6):640-4. PMID: 25003439 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/SAP.0000000000000242

30. Zhong T, Temple-Oberle C, Hofer S, Beber B, Semple J, Brown M, et al.; MCCAT Study Group. The Multi Centre Canadian Acellular Dermal Matrix Trial (MCCAT): study protocol for a randomized controlled trial in implant-based breast reconstruction. Trials. 2013;14:356. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1745-6215-14-356

1. Hospital Daher Lago Sul, Brasília, DF,

Brazil

2. Hospital de Base do Distrito Federal, Brasília,

DF, Brazil.

Corresponding author: Marcela Caetano Cammarota SMHN, Quadra 2, Bloco C, Ed Crispim, sala 1315 - Brasília, DF, Brazil Zip Code 70710-149 E-mail: marcelacammarota@yahoo.com.br

Article received: April 2, 2018.

Article accepted: February 10, 2019.

Conflicts of interest: none.

Read in Portuguese

Read in Portuguese

Read in English

Read in English

PDF PT

PDF PT

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to Cite

How to Cite

Mendeley

Mendeley

Pocket

Pocket

Twitter

Twitter