Original Article - Year 2019 - Volume 34 -

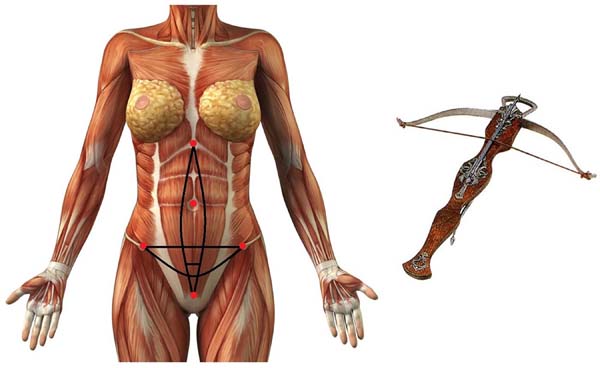

Abdominal wall treatment with plication using the crossbow technique

Tratamento da parede abdominal com plicatura em Crossbow

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Owing to the need to deliver results with greater definition in abdominoplasties, techniques must evolve. The objective of this study was to introduce the crossbow technique for plication along with its three variants that reinforces the concept of vertical and horizontal alignments of the aponeurosis of the rectus and oblique abdominis muscles at the same time, promotes 2 different traction vectors, and culminates in a greater definition of the abdominal wall, mainly in the hypogastrium and iliac fossa regions.

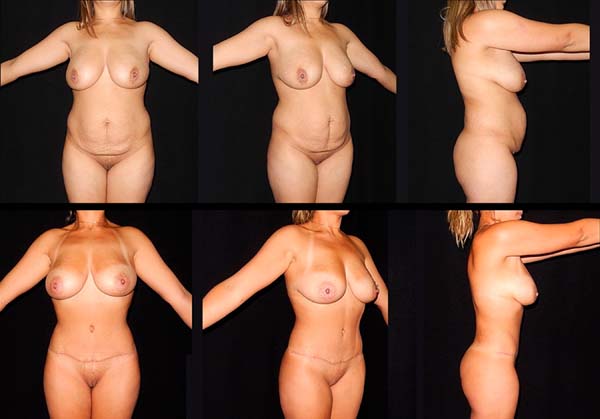

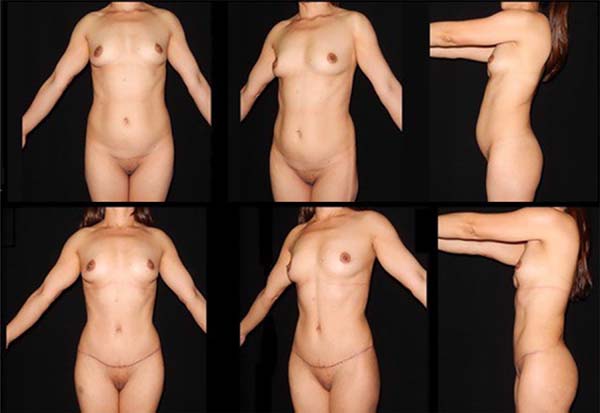

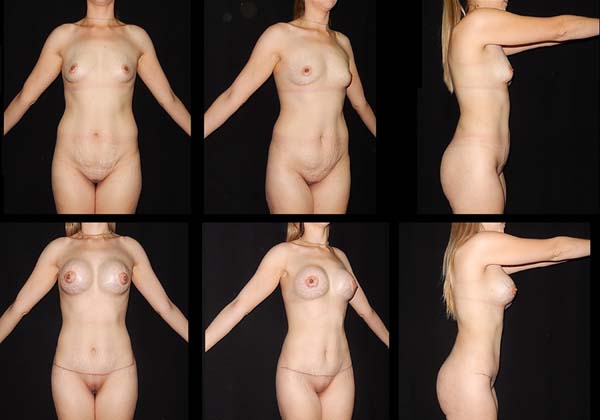

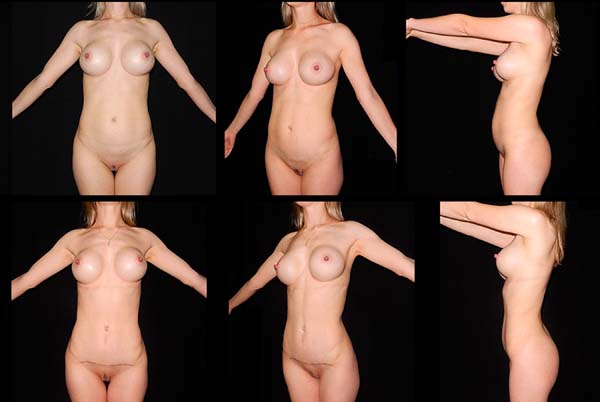

Methods: From January 2016 to February 2018, 22 surgeries were performed exclusively with the types l, ll, or lll crossbow technique, both in esthetic surgery cases and post-bariatric patients.

Results: The results were favorable both from the esthetic point of view, with greater definition of the hypogastrium, and from a clinical point of view, as none of the patients showed signs or symptoms different from those of the conventional techniques.

Conclusion: The crossbow technique is a simple and reproducible tool in the medical armamentarium to improve abdominal esthetics. Although it promotes the strengthening of the hypogastric region, both for primary and secondary treatments of this region, only a sample size increase can demonstrate the possible advantages of the method.

Keywords: Abdominoplasty; Abdominal muscles; Abdominal wall; Reconstructive surgical procedures; Aponeurosis

RESUMO

Introdução: A necessidade de oferecer resultados com maior definição nas abdominoplastias nos compele a evoluir tecnicamente. O objetivo deste trabalho é apresentar a técnica de plicatura em Crossbow com suas três variantes, reforçando o conceito de aproximação vertical e horizontal da aponeurose dos músculos retos e oblíquos abdominais ao mesmo tempo, promovendo dois vetores diferentes de tração, culminando em uma maior definição da parede abdominal, principalmente na região do hipogastro e fossas ilíacas.

Métodos: No período entre janeiro de 2016 e fevereiro de 2018, foram realizadas 22 cirurgias exclusivamente com a técnica Crossbow em seus tipos l, ll e lll, tanto em pacientes estéticos como pós-bariátricos.

Resultados: Os resultados foram favoráveis tanto do ponto de vista estético, com maior definição do hipogastro, como do ponto de vista clínico, uma vez que nenhum paciente apresentou sinais ou sintomas diferentes de técnicas convencionais.

Conclusão: A técnica Crossbow é simples e reprodutível, sendo mais um agregante na armamentária para melhorar a estética abdominal. Apesar de promover o reforço da região hipogástrica, tanto para tratamento primário como secundário desta região, só o aumento da casuística poderá demonstrar as possíveis vantagens do método.

Palavras-chave: Abdominoplastia; Músculos abdominais; Parede abdominal; Procedimentos cirúrgicos reconstrutivos; Aponeurose

INTRODUCTION

The aesthetic demand for a perfect abdomen compels the plastic surgeon to constantly develop innovative surgical techniques. By contrast, it is imperative that the patient understand that not all variables that involve abdominal protrusion are susceptible to surgical correction. Bad posture, sedentary lifestyle, and obesity should, preferably, be corrected prior to surgery. Excess visceral fat, variation in collagen type with stronger or more fragile aponeuroses1,2, and the associated bone structure in the abdominal polygon3 can also change the outcome.

The crossbow technique was conceived by the present author from his experience in abdominal wall plication. Before developing this technique, the author used horizontal shortening of the rectus abdominis muscles3-6 and sometimes the rectus and oblique abdominis muscles4,5. The results showed large variations in the lower abdominal region, from excellent rectifications to residual bulging that required a second intervention to correct the bulging.

In an attempt to fix the residual bulging of the lower abdomen, from observations over time, the author moved the vectors of these plicatures until a vertical position was attained, which provided better retrusion of the region between the iliac fossa and the hypogastrium.

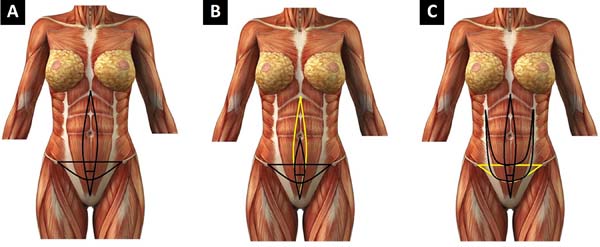

When migrating from secondary correction to primary indication, the conventional plicature (correction of the diastasis of the rectus abdominis and oblique abdominis muscles in the semilunar line) must be incorporated to the transverse arc plicature in the lower floor of the abdomen. This fusion gave rise to the crossbow technique with its variations, which appeared in all the samples. The types were defined as follows: type I, xiphopubic plication of the rectus abdominis (Figure 1, 2A); type II, mini-abdominoplasties and restriction of the detachment to the umbilical scar (Figure 2B); and type III, plication of the semilunar line concomitant with plication of the diastasis of the rectus abdominis muscles (Figure 2C).

The crossbow technique is indicated for patients who exhibit diastase of the linea alba, a semilunar line, and multidirectional enlargement, mainly in the lower floor of the abdomen, where we observed bulging containing only by the inguinal ligament and upper edge of the pubis, demonstrating esthetic failure in the containment of abdominal volume.

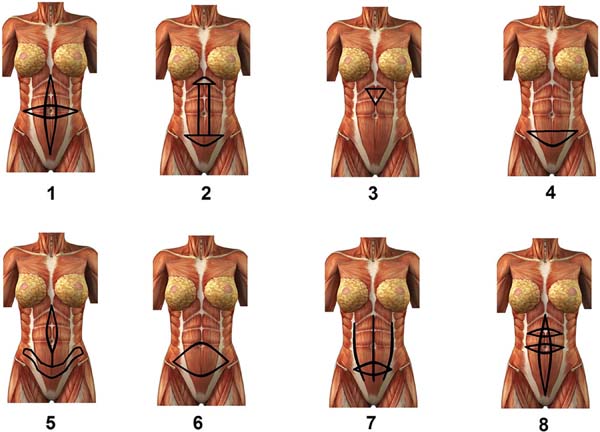

Studies using vertical or mixed abdominal wall traction vectors (Figure 3) were initially conducted by Jackson and Downie7 in 1978. Their cruciform plication technique foresaw plication of the diastasis of the rectus abdominis muscles and, at the same time, another plication with a transverse spindle, with the umbilical scar as the center of the intersection.

In 1999, Abramo et al.8 proposed a plication in the form of a horizontal “H” involving a small arciforme plication in the epigastrium, another arciforme plication in the lower region of the abdomen, and plication of the rectus abdominis muscles. In 2001, Ferreira et al. used a triangular suture in the aponeurosis of the rectus abdominis, in the epigastric region, promoting vertical and horizontal shortening that prevented residual epigastric bulging1. For mini abdominoplasties, Cárdenas Restrepo and Munoz Ahmed, in 20029, indicated a detachment limited to the umbilicus and preparation of a horizontal semilunar plication in the aponeurosis of the lower abdomen.

Cárdenas Restrepo and García Gutiérrez, in 200410, published a new technique with plicature in the anchor with the closing spindle of the diastasis of the rectus abdominis muscles and plication in a recurved horizontal arc in the lower floor of the abdomen, without the intersection of the 2 drawings. Villegas, in 201111, demonstrated his TULUA technique at the Vancouver Ipras World Congress, where he more broadly defended the systematic amputation of the umbilical stump and the confection of a large horizontal spindle in the aponeurosis throughout the lower abdomen, this being the only plication, promoting remarkable vertical shortening of the abdominal wall.

In 2013, Dr. Pamella Verissimo, at the Federal University of São Paulo, guided by Dr. Fabio Nahas, presented the study entitled, “Plication of the anterior lamina of the rectus abdominis sheath with the triangular suture technique”12. This work proved the maintenance of vertical shortening by imaging tests accompanied by metallic clips inserted in the abdominal wall. In 2013, Antônio Roberto Bozola, in his publication entitled, “27 years of observation by the author”4, exposed the need for a complementary horizontal spindle plication between the iliac fossae in cases of bulging in the hypogastrium.

More recently, in 2016, Gonzalez published his technique called smile plication13, which provides for the plication of the diastasis of the rectus abdominis muscles, concomitant to horizontal plication in the tendinous intersections of the rectus abdominis, aiming at an abdomen with more muscular appearance.

OBJECTIVE

The objective of this study was to demonstrate the plication using the crossbow technique and its variations, identify complications and conduct a double-blind comparative assessment, and observe the lower abdomen of these patients and other patients who received only plication of the rectus abdominis muscles.

METHODS

From January 2016 to February 2018, the author performed surgery with type I, II, or III crossbowplication in 22 patients (Table 1). In the preoperative period, the patients were evaluated with clinical and laboratory examinations, and an assessment of their cardiac surgical risk was performed by the anesthetic team. The patients’ ages ranged from 29 to 59 years; of the 22 patients, 21 were female and 1 was male.

| Plication type | Type I | Type II | Type III | Total no of Patients | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surgery type | |||||

| Abdominoplasty | 3 | 1 | 4 | ||

| Mini lipoabdominoplasty | 2 | 2 | |||

| Lipoabdominoplasty | 11 | 1 | 12 | ||

| Anchor dermolipectomy | 4 | 4 | |||

| Total | 18 | 2 | 2 | 22 | |

The patients were chosen according to the following criteria: underwent bariatric surgery with a body mass index (BMI) of <30 kg/m2, had an indication for anchor dermolipectomy, esthetic cases with a BMI of <28 kg/m2, had a history of multiparity, had no desire to conceive again, and had bulging of the lower abdomen. The exclusion criteria were relative and cover primiparous patients, patients who still had doubts about conceiving, and patients with clinical contraindication. In these cases, the plication were restricted conventionally to the rectus abdominis diastasis.

The study followed the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

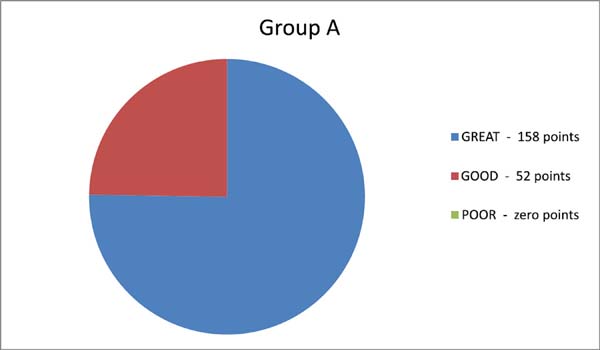

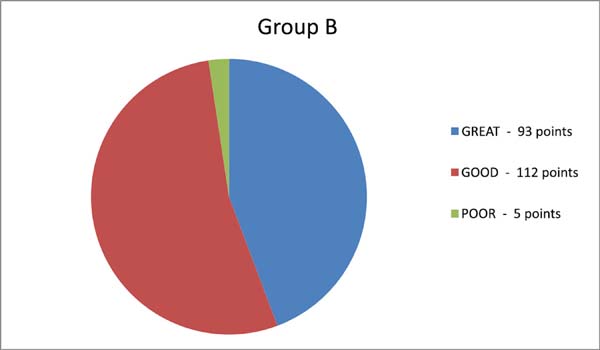

As rigid anthropometric measurements would be complex in relation to the abdomen owing to the number of variables, the author opted for an empirical evaluation and a double-blind study to compare 10 lipoabdominoplasty patients who underwent plication using the crossbow technique (group A) and 10 lipoabdominoplasties patients by the author, with an isolated plication of the diastase of the rectus abdominis muscles (group B).

The assessment took into account the observation of the horizontal distance of the anterosuperior iliac spine from the edge of the abdominal silhouette in the lateral view of the patient in the orthostatic position, with arms outstretched to the front at a 90° angle. Results were considered excellent when this distance was almost tangential, good when this distance did not exceed a harmonic silhouette (abdominal lyre), and poor when there was greater and inadequate distance and residual bulging of the hypogastrium.

By assigning 1 point for each vote of the 21 observers, we arrived at 210 points, and the following graphs were constructed (Graphics 1, 2 and Table 1):

Surgical procedure

At the surgical center, the patients received antibiotic prophylaxis and care to prevent venous thrombosis according to the modified Sandri protocol. All the patients underwent operation under routine epidural anesthesia with a catheter.

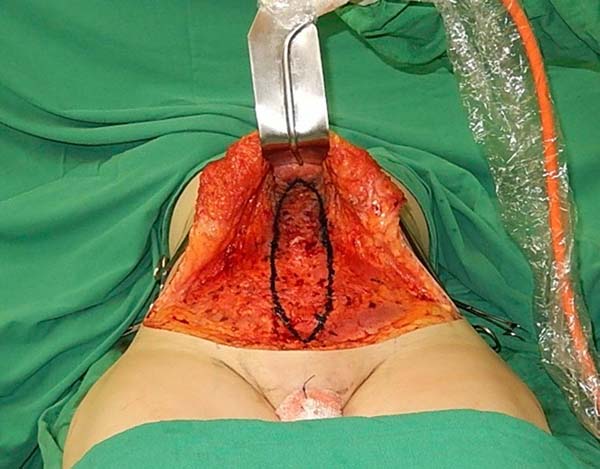

Type I crossbow plication was most frequently used (Figure 1, 2A). This technique begins with the patient in the dorsal decubitus position, and when indicated, liposuction is performed before abdominoplasty in the same procedure. After the due suprafascial detachment in the tunnel, similar to that recommended by Saldanha6, the following reference points are identified: the xiphoid appendix, upper edge of the pubis bone, right and left anterior superior iliac spines, and umbilical scar (Figura 1).

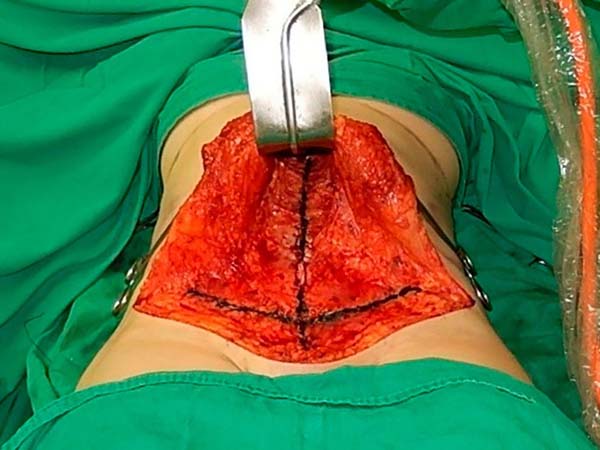

The marking begins by tracing the conventional zone for the treatment of the diastasis of the rectus abdominis muscles and, most often, the xiphoid appendix to the upper edge of the pubis (Figura 4). Then, a straight line is drawn that connects the anterosuperior right iliac spine to the left anterosuperior iliac spine, which we call the cord.

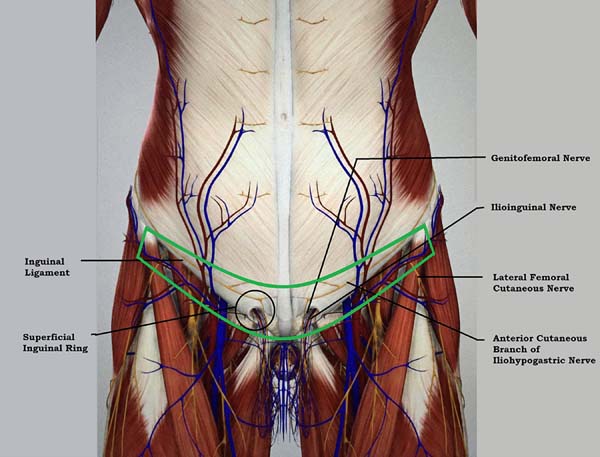

At this time, the space between the cord and the upper edge of the pubis is divided into three equal parts, within the marking of the plication of the rectus abdominis muscles. A second line, in the form of an arc, connects the anterior superior iliac spines, with the lowest point of this arc tangent to the second pubic cord space (Figure 5). The importance of this marking is the protection of the critical structures that border the inguinal region (Figure 6), avoiding their sequestration with the plicature (Figure 7).

With the patient in the supine position, we begin plication of the rectus abdominis muscles from the xiphoid appendix to near the points of intersection of the drawing, just below the umbilical scar. A more vigorous figure-8 polypropylene suture (Prolene 0 or similar suture) is applied in a figure-8 pattern, joining the four intersection sutures of the drawing, which facilitates the observation of the level of tension of this suture, the main suture of the technique. We then continue in the lower direction to plicate the pyramidal muscles with 2 or more sutures.

The next step is the horizontal plication of the aponeurosis of the external oblique muscle, from the center of the drawing outward until the anterosuperior iliac spines are reached. Sutures are all performed in shaped 8 pattern with the knot inverted, using Prolene 0 or a similar suture. Additional interrupted running sutures with Vicryl 0 (polyglactin) are also used as reinforcement on top of the Prolene sutures. The surgery continues with the resection of skin and subcutaneous tissue flaps, introduction of a suction drain, fixation of the umbilicus with Vicryl 0, closure of thefascia of Scarpa with Monocryl 3-0, subdermal sutures also with Monocryl 3-0, and micropore dressing.

Most cases will be solved with this technique, in Crossbow type 1 (Figure 8).

Special attention must be paid to patients with naturally low implantation of the umbilicus because vertical shortening of the abdomen causes the umbilical stump to be too low. In these cases, one must amputate the umbilical stump and prepare a new umbilicus in a higher position (Figure 9).

The technique can adapt to the need of a mini abdomen, with the detachment restricted to the umbilicus, only a small vertical spindle that connects the umbilicus to the pubis, and the conventional marking of the cord and arc (Figure 10).

In cases that need plication of the diastase of the semilunar line concomitant to plication of the rectus abdominis, we select the vertical spindle of the closure of the rectus abdominis, arc, and cord. However, the 2 ends of the arc should bend and follow the semilunar line, and no longer the anterosuperior iliac spines (Figure 11).

RESULTS

With regard to complications, one case of slight hematoma occurred in a patient with dermolipectomy in anchor, which was drained in the postoperative period. In a patient who underwent lipoabdominoplasty, persistent pain occurred in the right inguinal region but was resolved in 3 months. Two small sacral seromas (liposuction) and one seroma occurred in the lower abdomen but was resolved with puncture and compression. Another patient had a keloid after abdominoplasty. So far, reintervention to correct residual convexities in the lower abdominal region has never been required with this technique.

According to the comparative double-blind assessment, 5 observers classified the concept as poor in only three patients from group B (conventional plication) and in none of the patients in group A (crossbow). Group A attained a higher number of points for excellent concept than group B, whose major concept was classified as poor.

DISCUSSION

We know from previous studies that decreased waist and abdominal protrusions hold a direct relationship with the diastasis of the rectus14 and oblique abdominis muscles. Factors such as volumetric increase, type of collagen1,2 , and distension of the musculoaponeurotic fibers also induce this protrusion. Thus, in some patients who underwent lipoabdominoplasties, a residual bulging was observed in the lower abdomen in the postoperative period, despite the plication of the rectus and oblique abdominis muscles4. The hypothesis is that the increase in the musculoaponeurotic wall area was caused not only by the diastases of the linea alba and semilunar line but also by the multidirectional distention of its fibers9,12-14.

Below the arcuate line, only the transversalis fascia is observed, next to the inner surface of the rectus abdominis muscles15. These areas are susceptible to pressure and the weight of the abdominal contents, and to the effects of pregnancy, predisposing the patients toward greater flaccidity and protrusion. The use of vertical and horizontal traction vectors is assumed to attain both shortening and reinforcement of this region, thereby preventing or minimizing residual bulging7,8,10-13.

As the transversalis fasciadoes not offer as much resistance as the posterior aponeurosis of the rectus abdominis muscles, below the arcuate line, the rectus abdominis muscles can adapt without risk of compartmental syndrome. In this context, in the subcutaneous level, it is important to approximate the superficial fascia at the time of occlusion of the flaps before subdermal closure to prevent its retraction and subsequent division, which would increase the suprapubic bulging4-6,16.

The crossbow technique was initially developed for secondary abdomens and, subsequently, introduced in primary abdomens to prevent myofascial bulging in the hypogastrium.

Multiparous, post-bariatric patients, or those with a large distension on the lower floor of the abdomen are ideal indications for this technique.

The consequences of gestation in the patients who underwent crossbow plicature were not evaluated; thus, it is recommended that patients undergo this procedure only after they have given birth and if they do not wish to conceive further.

CONCLUSION

The crossbow technique is simple, standardized, and reproducible. Possible complications are the same as those of the conventional techniques. According to the author’s preliminary assessment, in principle, the technique contributes to the shortening and strengthening of the abdominal wall, improving the contour of the iliac fossa and hypogastric region. According to the observers, none of the 10 patients with crossbow plication had a residual bulging in the hypogastrium. The expectation is that with the increase in the sample size, a conclusion can be reached about the possible advantages of the method and its applicability.

COLLABORATIONS

|

ISF |

Analysis and/or data interpretation, conception and design study, conceptualization, data curation, final manuscript approval, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, project administration, realization of operations and/or trials, resources, supervision, validation, visualization, writing - original draft preparation, writing - review & editing. |

REFERENCES

1. Nahas FX, Barbosa MV, Ferreira LM. Factors that may influence failure of the correction of the musculoaponeurotic deformities of the abdomen. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124(1):334-5. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181a83998

2. Silva FAS, Ferreira LM, Nahas XF, Barbosa MVJ, Calvi ENC, Iurk LK. Imunohistoquímica do colágeno no músculo reto do abdome. Rev Bras Cir Plast. 2012; 27(3 Suppl):3.

3. Pitanguy I. Abdominal lipectomy. Clin Plast Surg. 1975;2(3):401-10.

4. Bozola AR. Abdominoplastias: efetividade da classificação de Bozola e Psillakis- 27 anos de observação do autor. Rev Bras Cir Plast. 2013;28(4):633-42.

5. Nahas FX. An aesthetic classification of the abdomen based on the myoaponeurotic layer. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;108(6):1787-97. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/00006534-200111000-00058

6. Saldanha OR. Lipoabdominoplastia. Rio de Janeiro: DiLivros; 2004.

7. Jackson I, Downie PA. Abdominoplasty--the waistline stitch and other refinements. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1978;61(2):180-3.

8. Abramo AC, Casas SG, Oliveira VR, Marques A. H-Shaped, double-contour plication in abdominoplasty. Aesth Plast Surg. 1999;23(4):260-6. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s002669900279

9. Cardenas Restrepo JC, Munoz Ahmed JA. New technique of plication for miniabdominoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;109(3):1170-7; discussion 8-90.

10. Cárdenas Restrepo JC, García Gutiérrez MM. Abdominoplasty with anchor plication and complete lipoplasty. Aesthetic Surg J. 2004;24:418-22. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asj.2004.07.004

11. Villegas Alzate FJ. Abdominoplasty without flap elevation, full liposuction, transverse infraumbilical plication and neoumbilicoplasty with skin graft (T.U.L.U.A). Can J Plast Surg. 2011;19(A):95.

12. Verissimo P. Plicatura da lâmina anterior da bainha dos músculos retos do abdome com a técnica de sutura triangular [Dissertação]. São Paulo: Universidade Federal de São Paulo. Programa de Pós-Graduação em Cirurgia Translacional; 2013.

13. Gonzáles HO. "Smile" Plication Abdominoplasty. In: Di Giuseppe A, Shiffman MA, eds. Aesthetic Plastic Surgery of the Abdomen. New York: Springer; 2016. p. 127-40.

14. Brauman D. Diastasis recti: clinical anatomy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;122(5):1564-9. PMID: 18971741 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181882493

15. Jaimovich CA, Mazzarone F, Navarro Parra JF, Pitanguy I. Semiologia da Parede Abdominal: Seu Valor no Planejamento das Abdominoplastias. Rev Bras Cir Plast. 1999;14(3):21-50.

16. Barcelos FVT, Avelar LET, Bordoni LS, Barcelos RVT. Análise anatômica da abdominoplastia. Rev Bras Cir Plast. 2017;32(2):272-81.

1. Hospital Policlínica São Vicente de Paula,

Francisco Beltrão, PR, Brazil

2. Hospital São Francisco de Assis, Francisco

Beltrão, PR, Brazil.

Corresponding author: Israel Soares Filho Av. Julio Assis Cavalheiro, nº 605, Apt. 162 - Centro, Francisco Beltrão, PR, Brazil Zip Code 85601-000 E-mail: israpoint@gmail.com

Article received: March 20, 2018.

Article accepted: November 11, 2018.

Conflicts of interest: none.

Read in Portuguese

Read in Portuguese

Read in English

Read in English

PDF PT

PDF PT

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to Cite

How to Cite

Mendeley

Mendeley

Pocket

Pocket

Twitter

Twitter