Original Article - Year 2019 - Volume 34 - Issue 1

Perioperative systematization for the prevention of hematomas following face-lift procedures: a personal approach based on 1,138 surgical cases

Sistematização perioperatória para prevenção de hematomas em face-lifts: abordagem pessoal após 1.138 casos operados

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Hematoma, the most frequent complication of face-lift procedures, may require a second surgical approach, which delays patient recovery. In the literature, its incidence ranges from 0.2% to 8%, and further studies are essential to standardize preventive measures. The objective is to present a proposal of perioperative systematization for effectively prevention of hematoma formation after rhytidectomies.

Methods: We analyzed the medical records of 594 patients who underwent operation by the author between 2011 and 2018 to compare the incidence of hematomas before and after the systematization implemented in 2015.

Results: From July 2011 to December 2014, before the adoption of the systematization, the incidence of hematomas was 3.43% in 233 cases. After its adoption, the incidence decreased to 1.66% in 361 cases. The last 177 consecutive cases did not have this complication.

Conclusion: We observed a significant reduction in the incidence of hematomas following rhytidectomy after the use of the proposed standardization. None of the measures would be effective alone; thus, their combined adoption is essential in preventing this serious complication.

Keywords: Rhytidectomy; Hematoma; Protocols; Postoperative complications.

RESUMO

Introdução: O hematoma, complicação mais frequente do face-lift, pode exigir reabordagem cirúrgica e atrasar a recuperação do paciente. Na literatura, sua incidência varia entre 0,2 e 8%, sendo fundamentais novos estudos para padronização das medidas de prevenção. O objetivo é apresentar uma proposta de sistematização perioperatória que previna eficientemente a formação de hematomas em ritidoplastias.

Métodos: Foram analisados 594 prontuários de pacientes operados pelo autor entre os anos de 2011 a 2018 a fim de se comparar as incidências de hematomas anteriores e posteriores à sistematização implementada no ano de 2015.

Resultados: De julho de 2011 a dezembro de 2014, antes da adoção da sistematização, houve uma incidência de hematomas de 3,43% em 233 casos. Após sua adoção, houve uma queda para 1,66% em 361 casos realizados. Os últimos 177 casos consecutivos não apresentaram a complicação.

Conclusão: Observamos redução expressiva da incidência de hematomas pósritidoplastias após o uso da padronização proposta. Nenhuma das medidas adotadas seria eficiente isoladamente, sendo o conjunto essencial na prevenção desta grave complicação.

Palavras-chave: Ritidoplastia; Hematoma; Protocolos; Complicações pós-operatórias

INTRODUCTION

Initially, attempts to treat wrinkles were based on resections of skin bands associated with broad tissue detachment, with short-term results and poor-quality scars1-4. Indeed, superficial muscular aponeurotic system (SMAS) treatments represent a wide evolution in face-lift surgery, with more lasting and natural results than other treatments1-4.

The search for more efficient operative techniques or tactics with better results, always associated with greater safety and lower incidence of complications in the short and long term, continues until today1,3-5.

Despite the ongoing improvement, the most frequent complication of face-lift surgery continues to be hematoma, which when of large proportions, may compromise flap vascularization, for which another urgent surgical approach is required (expansive and/or voluminous case), significantly delaying patient recovery. It can also prolong the time of edema and ecchymoses, with risks of developing necrosis, dyschromia, and irregularities in the skin after healing6-9.

According to the literature, the incidence of hematomas following face-lift procedures ranges from 0.2% to 8%, and in men, the incidence can reach 12.9%8-10 (Table 1).

| Authors | Year | No. of cases of hematoma | Incidence (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before 1980† | ||||

| Serson-Nesto | 1964 | 170 | 2 | 1.2 |

| Galozzi et al. | 1965 | 100 | 3 | 3.0 |

| Conway | 1970 | 325 | 21 | 6.6 |

| McGregor and Greenberg | 1971 | 524 | 42 | 8.0 |

| McDowell | 1972 | 105 | 3 | 2.9 |

| Webster | 1972 | 221 | 2 | 0.9 |

| Pitanguy et al. | 1972 | 1600 | 89 | 5.5 |

| Rees et al. | 1973 | 806 | 23 | 2.9 |

| Barker | 1974 | 163 | 2 | 1.3 |

| Black | 1976 | 1804 | 48 | 2.7 |

| Baker et al. | 1977 | 1500 | 46 | 3.0 |

| Stark | 1977 | 500 | 13 | 2.6 |

| Leist et al. | 1977 | 324 | 19 | 5.9 |

| Straith et al. | 1977 | 500 | 8 | 1.6 |

| Thompson and Ashley | 1978 | 922 | 44 | 5.0 |

| Lemmon and Hamra | 1980 | 577 | 5 | 0.8 |

| Total | 10141 | 370 | 3.6 | |

| After 1980‡ | ||||

| Matsunaga | 1981 | 427 | 1 | 0,2 |

| Fodor | 1982 | 100 | 1 | 1,0 |

| Owsley | 1983 | 435 | 6 | 1,4 |

| Lemmon | 1983 | 1445 | 8 | 0,5 |

| Shirakabe | 1988 | 738 | 9 | 1,2 |

| Rees et al. | 1994 | 1236 | 23 | 1,9 |

| Marchac and Sandor | 1994 | 412 | 17 | 4,2 |

| Heinreichs and Kaidi | 1999 | 200 | 2 | 1,0 |

| Kamer and Song | 2000 | 451 | 10 | 2,2 |

| Grover et al. | 2001 | 1078 | 45 | 4,2 |

| Total | 6522 | 122 | 1,9 | |

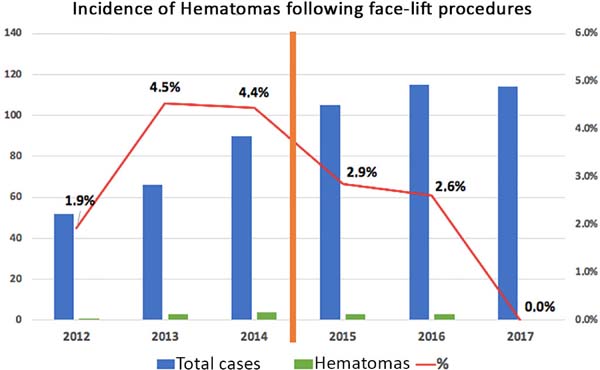

Several measures have been taken to reduce the incidence of hematomas, such as blood pressure (BP) control in the perioperative and postoperative periods, dressings, drains, fibrin glue, and platelet gel7,9,10. Nevertheless, hematoma persists as the main complication of face-lift procedures, with the constant analysis and study of cases being essential for better standardization of preventive measures for this significant complication (Figures 1A and 1B).

OBJECTIVE

This study aimed to present a proposal of perioperative and postoperative systematization for the prevention of hematoma formation after rhytidectomies by analyzing current literatures, a series of cases, and the author’s personal experience.

METHODS

The author has been performing face-lift procedures since 1992. Over the years, several changes in approaches have been proposed to improve results and reduce complications. Since 2015, the author has been using complete systematization, which is presented below and in Chart 1. The data of all the cases analyzed in this article were collected from medical records of the institution, whose clinical director is the main author. The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

| Preoperative measures |

| Hospital environment |

| Long-term indwelling urinary catheterization (until hospital discharge) |

| Intraoperative measures |

| General anesthesia |

| Pneumatic compression of LL (for DVT prophylaxis) |

| Infiltration of approximately 100 mL of 0.375% + lidocaine solution in each hemiface |

| Adrenaline at 1:600,000 |

| Definitive hemostasis - 20 minutes per hemiface |

| Under SBP 130 mmHg (never under hypotension) |

| Reduction of dead space: eight Baroudi sutures + use of fibrin glue |

| Postoperative measures |

| Maintain the head high |

| Dressing using low-compression elastic mesh |

| Cold saline solution compresses + frozen gel bag (1/1h) |

| Administration of antiemetics at fixed times |

| Rigorous BP control (1 h/1 h) - Intravenous administration of clonidine if SBP 140 mmHg |

| Pneumatic compression of the LL during the entire hospitalization |

| LMWH - start the morning after surgery |

| Do not walk in the first 24 hours (during hospitalization) |

| Hospital discharge only in the morning following surgery and if BP is under control |

| Outpatient reevaluation within 48 hours |

All the face-lift procedures were performed in a hospital environment, with the patient under general anesthesia and with noninvasive BP monitoring and indwelling urinary catheterization.

Approximately 100 mL of 0.375% lidocaine solution was infiltrated by hemiface, with adrenaline at 1:600,000. Although some authors avoid such infiltration because of the risk of vasodilation rebound after the use of adrenaline solution10, we believe that this approach facilitates detachment and visualization of the appropriate surgical plan, in addition to minimizing intraoperative bleeding and facilitating definitive hemostasis7,8.

The surgical time for hemostasis is never <20 minutes for each hemiface and is always performed with systolic pressure values of ≥130 mmHg. Definitive hemostasis should never be performed in hypotension.

In all the cases, we used quilting sutures with absorbable stitches between the detached flap and the SMAS, similar to Baroudi’s stitches in abdominoplasties11,12.

Generally, eight stitches were distributed in each hemiface to hinder the expansion of an eventual hematoma, besides reducing the dead space and facilitating the adhesion of the flap (Figure 2).

We routinely used fibrin glue (Tessel®) in the detached area of the face and neck with the intention of improving flap adhesion, enhancing hemostasis, and preventing hematomas (Figure 3).

We did not use a drain, and the dressing was made with a low compressive elastic mesh and compresses soaked in cold saline solution, which were renewed every hour. Moreover, we placed frozen gel bags on the compresses, which were also renewed systematically every hour. The objective was to generate vasoconstriction in the first hours and inhibit bleeding.

All the dressing was removed the next morning at the time of discharge, and the patients continued to use the frozen gel bags over the hemifaces (always with the skin protected) at home, 30 minutes at a time and with intervals of 1 hour for a total period of 48 hours (except at night to sleep).

During hospitalization, all the patients were instructed to remain with their heads held at approximately 30°. We also prescribe medications with a fixed schedule for the prevention of vomiting, and we maintained strict BP control with reevaluations every hour. When the systolic BP reached 140 mmHg, we initiated antihypertensive treatment, usually with intravenous clonidine.

As the patients were probed, they were not allowed to get up during the entire hospitalization, not even to go to the bathroom, because we believe that immobilization reduces the risk of bleeding. To reduce the risk of deep vein thrombosis, all the patients wore intermittent compression boots throughout the surgery and hospitalization. Moreover, they started using lowweight heparin the morning after the surgery, before discharge from the hospital.

All the patients stayed overnight in the hospital, were discharged in the morning after the surgery, and were reevaluated at the physician’s clinic 48 hours after discharge, when lymphatic drainage by the physiotherapy team already started.

For didactic purposes, we considered as hematomas only those cases that required drainage for hematomas, even small ones, during, for example, suture removal or new incisions, in a hospital environment in patients undergoing surgical interventions. They cause significant distortions in the face, threaten the integrity of the skin flaps due to the great distension they cause, and require prompt emptying. The small blood collections that eventually form during the postoperative period in a localized manner and without causing harm to the flap were disregarded. Usually, they are benign occurrences that are drained in the physician’s clinic with punctures, commonly after the 10th day, when they are liquefied.

RESULTS

From January 1992 to March 2018, a period longer than 26 years, the author performed 1,138 face-lifts procedures, a number close to that performed by Rohrich in a 23-year analysis4,8. Since August 2013, the author has been working exclusively with facial plastic surgery.

Reliable records on the occurrence of hematomas have been available since July 2011. Therefore, all data from the medical records dated since then were included in the analysis.

From July 2011 to December 2014, the period prior to the adoption of systematization, 233 patients underwent face-lift procedures, of whom 8 had a hematoma (incidence of 3.43%).

Since January 2015, we used the aforementioned systematization and had, until March 2018, 6 cases of hematomas in 361 surgeries (incidence, 1.66%). All the bruises occurred in the first 48 hours after surgery.

Thus, with the introduction of the new measures, we obtained a 48.4% reduction in our hematoma rates. The Fischer exact test did not show statistical significance for these results (p > 0.05).

The set of measures used seems to have led to this significant reduction, which we observed to be continually occurring. In the last 19 months included in the analysis, 177 consecutive face-lift procedures were performed, in which no occurrence of this complication was observed.

Figure 4 shows the significant decrease in the incidence of hematomas after the beginning of the use of systematization, despite the progressive increase in the number of surgical cases in the same period. The number of cases increased from 52 in 2012 to 114 cases in 2017. To avoid distortions, the graph included only the years when data were collected over the 12 months (Figure 4).

DISCUSSION

Several factors are associated with the formation of hematomas following face-lift procedures, including the type of anesthesia, age, sex, surgical technique, the combination of procedures, use of drains, and BP9. We observed that the data were not enough to determine the specific cause responsible for the formation of hematomas following rhytidectomy9,10. Therefore, a set of measures is necessary for its prevention.

Adequate techniques and anesthesia care are vital components to prevent preoperative and postoperative complications. Specifically, in the prevention of hematomas after rhytidectomy, the control of BP, heart rate, anxiety, analgesia, and vomiting are essential13.

In the immediate preoperative period, the patients received benzodiazepines to reduce anxiety and enhance the effect of the sedative medication. Despite the good results achieved by some authors with the use of local anesthesia associated with intravenous sedation9, we chose to always perform these surgeries under general anesthesia, as we believe that patients remain better monitored and controlled, with airways assured during head movements and a closed system for oxygen delivery, which allow safe use of electrocautery8,13.

During the preparation for surgery, we infiltrated a 0.375% lidocaine solution with adrenaline at 1:600,000 in each hemiface; some authors prefer not to perform this procedure because of the potential risk of rebound vasodilatation10. However, like most surgeons, we believe that this approach optimizes the detachment and visualization of the appropriate surgical plan, in addition to minimizing intraoperative and postoperative bleeding, which greatly facilitates definitive hemostasis6-13.

Of all the factors responsible for the formation of hematomas following rhytidectomy, hypertension is certainly the main factor, a fact well documented by several authors such as Baker, Knize, Ramanadham, and Rohrich7-13. Regardless of the perioperative approach proposed by each author, agreement is always reached that strict control of intraoperative and postoperative pressures is associated with the reduction of the incidence rates of hematomas following face-lift7-13. Baker reported in his study on hematomas in men that strict BP control reduced the incidence from 8.7% in 1977 to 3.97% in 20059,13,14.

BP just below normal or even mild hypotension is tolerated during facial flap detachment to minimize perioperative bleeding. However, definitive hemostasis under hypotension should never be performed because of the risk of masking injured perforating vessels that could bleed significantly in the postoperative period after the expected rebound increase in BP7-16. Routinely, we perform hemostasis after the systolic BP reaches ≥130 mmHg.

Rohrich et al. recommend the use of 0.1- to 0.2- mg transdermal clonidine adhesive per day before entering the operating room, with maintenance for up to 7 days in the postoperative period4,7,8,13,14. Rohrich justifies this prolonged use on the basis of the observation that hypertensive peaks are more common in the postoperative period than in the intraoperative or immediate postoperative period8.

In our routine, we use intravenous clonidine during hospitalization when the systolic BP reaches 140 mmHg. We consider that the constant use of a transdermal clonidine adhesive increases the risk of hypotension in the first postoperative days and, consequently, increases the risk of falls and consequent trauma.

Furthermore, other factors such as anxiety, pain, urinary retention, nausea, and vomiting are directly associated with increased BP and, consequently, the formation of hematomas7-15. They must be adequately prevented. In our routine practice, antiemetic medication is used at a fixed time, starting even before the patient’s anesthetic awakening, a protocol also adopted by Baker and Rohrich9,13,14. All the patients received indwelling urinary catheterization during the entire hospitalization.

In all the cases, we used quilting sutures between the dermis of the detached flap and the SMAS; we consider this step important for reducing dead space (improving flap adhesion) and limiting the dissemination of any hematoma that may form. These sutures are similar to Baroudi’s sutures in abdominoplasties and have already been described in rhytidectomies by the same surgeon11,12.

In addition to these quilting sutures, we used fibrin glue (Tessel®) to provide better adhesion to the detached and pulled flap, besides preventing the formation of hematomas. The use of fibrin glues and other flap adhesion mechanisms is controversial. Fibrin sealants have demonstrated good efficacy in controlling slow and focal bleeding or diffuse bleeding9,17,18. While some authors such as Marchac and Sándor19 reported that after the use of fibrin glue in aerosol under the detached flap, they observed a decrease in the incidence of hematomas. Others such as Fezza et al.20 reported only a reduction in edema and ecchymosis, without statistically significant differences in the incidence of hematomas. The plateletbased sealing gel is an alternative, but further studies are needed to define its potential in the prevention of hematomas17.

Still in the operating room, soon after surgery, the patients were positioned with their head elevated to 30° and received cold compresses on their face, which were systematically changed every 30 minutes, to generate vasoconstriction. After hospital discharge, we recommended strict maintenance of ice therapy 30 minutes for 48 to 72 hours.

According to the literature, the incidence of hematomas following face-lift is 0.2% to 8%, and in men, this incidence can reach 12.9%8-16.

Before the adoption of the systematization in 2015, we observed an incidence of 3.43%, and after implementation, the incidence became 1.66%, which represents a decrease of approximately 48.4%. The current index is close to the lower limits reported in the literature. With the data analyzed, we did not reach statistical significance. However, it is important to emphasize that the incidence has been decreasing, as the last 177 cases analyzed showed no incidence of hematomas.

CONCLUSION

After analyzing our series of cases and the data in the literature, we observed a significant reduction in the incidence of hematomas following rhytidectomy over the years with the use of the proposed standardization. The set of proposed measures acts synergistically to reduce the incidence of this serious complication. In our opinion, none of these measures alone would be able to achieve such a reduction in hematoma index.

Although the sample size was insufficient to prove statistical significance (p > 0.05), we are convinced that the numbers are promising. Despite that hematoma is the most frequent complication in face-lift surgery, the number of surgeries was relatively small, which makes the expansion of the series of cases essential to obtain more robust data. However, it is important to emphasize that systematization has been progressively consolidated in our service, and consistency must be maintained in the application of the protocol, and the adequate data must be collected, always with the aim of obtaining the best possible outcome for the patient.

COLLABORATIONS

|

TCTC |

Analysis and/or data interpretation, conception and design study, conceptualization, data curation, final manuscript approval, investigation, methodology, project administration, realization of operations and/ or trials, resources, supervision, visualization, writing - original draft preparation, writing - review & editing. |

|

WFFJ |

Analysis and/or data interpretation, conception and design study, final manuscript approval, investigation, project administration, visualization, writing - original draft preparation, writing - review & editing. |

|

CEGL |

Analysis and/or data interpretation, conception and design study, final manuscript approval, methodology, project administration, supervision, writing - review & editing. |

|

FXC |

Analysis and/or data interpretation, conception and design study, data curation, final manuscript approval, formal analysis, writing - original draft preparation, writing - review & editing. |

|

LML |

Analysis and/or data interpretation, conception and design study, data curation, final manuscript approval, formal analysis, writing - review & editing. |

|

LRL |

Analysis and/or data interpretation, conception and design study, data curation, final manuscript approval, formal analysis, writing - review & editing. |

REFERENCES

1. Pontes R. O Universo da Ritidoplastia. Rio de Janeiro: Revinter; 2011.

2. Pitanguy I, Radwanski HN, Amorim NFG. Treatment of the Aging Face Using the "Round-lifting" Technique. Aesthet Surg J. 1999;19(3):216-22.

3. Castro CC. Ritidoplastia: Arte e Ciência. 1ª ed. Rio de Janeiro: Di Livros; 2007.

4. Rohrich RJ, Narasimhan K. Long-Term Results in Face Lifting: Observational Results and Evolution of Technique. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016;138(1):97-108. PMID: 27348643 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0000000000002318

5. Rohrich RJ, Ghavami A, Mojallal A. The five-step lower blepharoplasty: blending the eyelid-cheek junction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;128(3):775-83. PMID: 21278622 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182121618

6. Warren RJ, Neligan P. Cirurgia Plástica: Estética. 3a ed. Rio de Janeiro: Elsevier; 2015. p. 184-207.

7. Costa CR, Ramanadham SR, O'Reilly E, Coleman JE, Rohrich RJ. The Role of the Superwet Technique in Face Lift: An Analysis of 1089 Patients over 23 Years. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;135(6):1566-72. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0000000000001131

8. Ramanadham SR, Mapula S, Costa C, Narasimhan K, Coleman JE, Rohrich RJ. Evolution of hypertension management in face lifting in 1089 patients: optimizing safety and outcomes. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;135(4):1037-43.

9. Baker DC, Stefani WA, Chiu ES. Reducing the incidence of hematoma requiring surgical evacuation following male rhytidectomy: a 30-year review of 985 cases. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;116(7):1973-85.

10. Jones BM, Grover R. Avoiding hematoma in cervicofacial rhytidectomy: a personal 8-year quest. Reviewing 910 patients. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;113(1):381-7.

11. Baroudi R, Ferreira CA. Seroma: how to avoid it and how to treat it. Aesthet Surg J. 1998;18(6):439-41. PMID: 19328174 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1090-820X(98)70073-1

12. Destro MWB, Destro C, Baroudi R. Pontos de adesão nas ritidoplastias: estudo comparativo. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2013;28(1):55-8. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1983-51752013000100010

13. Ramanadham SR, Costa CR, Narasimhan K, Coleman JE, Rohrich RJ. Refining the anesthesia management of the face-lift patient: lessons learned from 1089 consecutive face lifts. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;135(3):723-30. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0000000000000966

14. Rohrich RJ, Stuzin JM, Ramanadham S, Costa C, Dauwe PB. The Modern Male Rhytidectomy: Lessons Learned. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;139(2):295-307. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0000000000003008

15. Goldwyn RM. Late bleeding after rhytidectomy from injury to the superficial temporal vessels. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1991;88(3):443-5. PMID: 1871221 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00006534-199109000-00010

16. Pitanguy I, Ramos H, Garcia LC. Filosofia, técnica e complicações das ritidectomias através da observação e análise de 2.600 casos pessoais consecutivos. Rev Bras Cir. 1972;62:277-86.

17. Brown SA, Appelt EA, Lipschitz A, Sorokin ES, Rohrich RJ. Platelet gel sealant use in rhytidectomy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;118(4):1019-25. PMID: 16980865

18. Mustoe T, Silvati-Fidell L, Desmond J, Mannion-Henderson J, Abrams S, Hester TR. Reduced hematoma/seroma occurrence with the use of fibrin sealant during facial rhytidectomy: results of an integrated analysis of phase 2 and phase 3 study data. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;128(Supp.4):7.

19. Marchac D, Sándor G. Face-lifts and sprayed fibrin glue: an outcome analysis of 200 patients. Br J Plast Surg. 1994;47(5):306-9. PMID: 8087367

20. Fezza JP, Cartwright M, Mack W, Flaharty P. The use of aerosolized fibrin glue in face-lift surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;110(2):658-64.

1. Cló & Ribeiro Cirurgia Plástica, Belo

Horizonte, MG, Brazil

2. Clínica Leão, Belo Horizonte, MG,

Brazil

3. Universidade Católica de Minas Gerais,

Faculdade de Medicina, Betim, MG, Brazil

4. Fundação José Bonifácio Lafayette de Andrada,

Faculdade de Medicina de Barbacena, Barbacena, MG, Brazil.

Corresponding author: Ticiano Cesar Teixeira Cló Alameda Oscar Niemeyer, nº 1268 - Vila da Serra, Nova Lima, MG, Brazil Zip Code 34006-065 E-mail: ticianoclo@gmail.com / felipeclo@hotmail.com

Article received: August 31, 2018.

Article accepted: November 11, 2018.

Conflicts of interest: none.

Read in Portuguese

Read in Portuguese

Read in English

Read in English

PDF PT

PDF PT

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to Cite

How to Cite

Mendeley

Mendeley

Pocket

Pocket

Twitter

Twitter