Original Article - Year 2018 - Volume 33 -

Thoracic wall reconstruction using myocutaneous and fasciocutaneous flaps in patients with locally advanced and metastatic breast cancer

Reconstrução de parede torácica com retalhos musculocutâneos e fasciocutâneos em pacientes com câncer de mama localmente avançado e metastático

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Breast cancer is the most common cancer

among women worldwide. Locally advanced breast cancer is

characterized by clinical stage IIIb or IV and accounts for 20-

25% of all cases. Defects are reconstructed using myocutaneous

and fasciocutaneous flaps, primarily from the latissimus dorsi

and rectus abdominis muscles. The objective is to evaluate

the results of thoracic wall reconstructions in cases of locally

advanced breast cancer using fasciocutaneous and myocutaneous

flaps.

Methods: This was a retrospective, observational, and

descriptive single-center study. Variables studied included defect

size and flap dimensions, myocutaneous flap type, presence of

cutaneous and visceral metastasis, postoperative evolution, and

complications.

Results: We selected 11 patients with a mean

age of 49 years; the left side was the most commonly affected.

The most common tumor type was invasive ductal carcinoma.

The flaps were made of latissimus dorsi VY (LDVY) in two

patients, latissimus dorsi associated with thoracoabdominal flaps

(LDVYTA) in two, vertical rectus abdominus myocutaneous

flap (VRAM) in four, and thoracoabdominal flaps (TA) in

three. The mean defect area was 421.72 cm2, while the mean

flap area was 451 cm2. The most frequent complication was

partial dehiscence (seven patients). Six patients achieved lethal

exit. VRAM flaps presented more complications. The mean

survival for VRAM was 25.5 months, LDVY was 17 months,

TA was 17 months, LDVYTA was 20.5 months.

Conclusion:

Myocutaneous and fasciocutaneous flaps are effective for chest

wall reconstruction after locally advanced breast cancer resection.

Keywords: Reconstructive surgical procedures; Thoracic wall; Breast neoplasms; Myocutaneous flap; Neoplasm metastasis; Fascia

RESUMO

Introdução: Câncer de mama localmente avançado é caracterizado pelos estádios clínicos

IIIb ou IV e representam de 20 a 25% de todos os casos. A reconstrução dos

defeitos é feita com retalhos musculocutâneos e fasciocutâneos, sendo os

mais utilizados o latíssimo do dorso e o reto abdominal. O objetivo é

avaliar resultados das reconstruções de parede torácica em câncer de mama

localmente avançados com retalhos musculocutâneos e fasciocutâneos.

Métodos: Estudo retrospectivo, observacional descritivo, em único centro. Variáveis

estudadas: dimensões do defeito e do retalho, tipo de retalho utilizado para

a reconstrução, metástases cutâneas e viscerais, evolução pós-operatória e

complicações.

Resultados: 11 pacientes, com média de idade de 49 anos, com o lado esquerdo mais

acometido. O tipo tumoral mais encontrado foi o carcinoma ductal invasivo.

Os retalhos realizados foram: 2 latíssimos do dorso com desenho VY (LDVY), 2

latíssimos do dorso associados a retalho toracoabdominal (LDVYTA), 4

verticais do músculo reto do abdome (VRAM) e 3 toracoabdominais (TA). A área

média dos defeitos foi 421,72cm2 e a área média dos retalhos

utilizados foi de 451cm2. A complicação mais frequente foi

deiscência parcial da ferida operatória, presente em 7 pacientes. Da

amostra, 6 pacientes atingiram êxito letal. VRAM foi o retalho que

apresentou mais complicações. A sobrevida média para VRAM foi de 25,5 meses,

para LDVY de 17 meses, TA de 17 meses e LDVYTA de 20,5 meses.

Conclusão: Os retalhos musculocutâneos e fasciocutâneos são eficazes para a reconstrução

da parede torácica após a ressecção de neoplasias mamárias localmente

avançadas.

Palavras-chave: Procedimentos cirúrgicos reconstrutivos; Parede torácica; Neoplasias da mama; Retalho miocutâneo; Metástase neoplásica; Fáscia

INTRODUCTION

The reconstruction of chest wall defects is challenging and involves shape and function restoration as well as vital structure coverage and protection1,2. Advances in surgical techniques, mechanical ventilation, intensive therapy support, broad-spectrum antibiotics, and anesthesia allowed broader resections with acceptable morbidity and mortality rates, improving patient prognosis. An increased understanding and management of the ventilatory dynamics is a determinant of the evolution of related procedures3.

The main indications for large thoracic wall resections include radiotherapy-induced necrosis, congenital defects, trauma, osteomyelitis, sarcomas, and advanced lung and breast neoplasms4.

Breast cancer is the most common cancer among women worldwide and after non- melanoma skin cancer in Brazil, accounting for about 28% of new cases each year. An increase in its incidence is reported in developed and developing countries. In Brazil, the estimate is 59,700 new cases in 2018 according to the National Cancer Institute and in 2013 there were 14388 registered deaths due to breast cancer5.

Locally advanced breast cancer is considered clinical stage IIIb or IV. Its occurrence comprises 20-25% of all cases and is characterized by a high local recurrence rate and heterogeneous behavior6,7. Stage IIIB involves T4 tumors classification that represents a tumor of any size with a direct extension to the chest wall or skin presenting as ulceration or cutaneous nodules. Clinical stage IV includes patients with any T, any N (lymph node status), and M1, which means metastatic disease, including the skin. Treatment with adjuvant chemotherapy is often considered in this clinical presentation before surgery, as well as radiotherapy7.

Tansini was the first surgeon to use a musculocutaneous flap to reconstruct the soft tissues of the anterior chest wall. The first case of closure of the defect resulting from a radical mastectomy with a latissimus dorsi flap was reported in 19068. There were other descriptions of flap transposition in the 40s9 and 50s10 for reconstruction of the chest wall2. The technique only started being widely used when the concept of myocutaneous flaps was revived and perfected in the 70s, securing its routine use to date1,2.

The main muscles used for chest wall reconstruction include the latissimus dorsi (LD), pectoralis major, and rectus abdominis; each has its advantages and disadvantages, yet all are robust, reliable, and versatile, with a consistent vascular anatomy and the possibility of using an associated skin island1,11.

Local and fasciocutaneous thoracoabdominal flaps are also useful in selected cases12. In some cases, use of the large omentum is described as a framework for chest wall reconstruction as demonstrated initially by Kiricuta13 and then by Tavares et al.14.

Researchers have attempted to develop algorithms11,15 for the reconstruction of the soft tissues of the chest wall; however, in practice, a great complexity and variety of defects is observed. The reconstructive surgeon must be prepared to change the surgical plan to meet the intraoperative findings1.

The choice of technique depends on defect location, donor area location and availability, previous surgical approaches in the thoracic and abdominal regions, and radiotherapy1,2.

OBJECTIVE

To evaluate the results of chest wall reconstructions using musculocutaneous and fasciocutaneous flaps in patients with locally advanced breast cancer at a referral hospital.

METHODS

This retrospective observational descriptive study was performed in a single center by the same surgeon. The studied population is composed of patients who underwent the resection of oncological lesions in the chest wall at the A. C. Camargo Cancer Center and reconstructed using musculocutaneous and fasciocutaneous flaps by the author from January 1, 2016 to December 31, 2017.

The study received approval from the institution’s ethics and research committee (code EC 51/18). All patients were informed of the procedures and signed an informed consent form.

The variables studied were age, sex, histology, defect size, myocutaneous flap type, flap dimensions, presence of cutaneous and visceral metastasis, postoperative evolution, and immediate and late complications.

To evaluate the postoperative complications, patients were divided into four groups by flap type: 1) vertical rectus abdominis myocutaneous flap (VRAM), 2) latissimus dorsi with VY skin island conformation (LDVY), 3) thoracoabdominal flap (TA), and 4) latissimus dorsi associated with the thoracoabdominal flap (LDVYTA).

The technique used to create the flaps is described below.

LD with VY skin island

The patients were placed in the lateral decubitus position. On the side opposite the mastectomy, a VY-skin island was demarcated over the LD muscle from the lateral margin of the mastectomy defect. A skin clamping test was used to evaluate the tension at the donor area closure. Next, infiltration with a 1:250,000 solution of adrenaline and 10 mg/mL ropivacaine was performed.

The thoracodorsal artery was dissected and the tendon in the intertubercular groove of the humerus was disinserted. The flap was transposed to the area of the mastectomy defect followed by the confection of 10 adhesion stitches with Vicryl 2.0. The donor area was closed in a “Y” shape after drainage with Blake drain no. 19.

The patient was then moved to the horizontal position, the flap distribution was performed on the mastectomy defect, a vacuum drain (Blake no. 19) was placed, and closure by planes was performed. When necessary, LDVYTA was used to complement the closure due to insufficient coverage of the LD flap.

The dressings of the donor area and reconstructed area were performed with Adaptic gauze and Opsite film.

VRAM flap

With the patient in the horizontal decubitus position, the skin island on the longitudinal axis of the contralateral monopediculate rectus abdominis muscle was demarcated to the defect of the mastectomy.

A 1:250,000 solution of adrenaline and 10 mg/mL ropivacaine was infused. Dissection by planes to the sheath of the rectus abdominis muscle with its opening was performed. The distal third of the rectus abdominis muscle was then incised in the projection of the semilunar line after ligation of the inferior epigastric artery and corresponding veins with Vicryl 2.0 knots. The flap was mobilized to the defect area and the donor area was closed with reconstitution of the anterior sheath of the rectus abdominis muscle with separate 0.0 nylon stitches. At this time, the need for reinforcement with an Ultrapro screen (Johnson & Johnson) was evaluated according to the closure tension. Vacuum drainage (Blake no. 19) was then performed and the donor area closed by planes.

The mobilized flap was then accommodated on the defect resulting from the mastectomy; vacuum drainage was performed with Blake’s drain no. 19 and closure by planes. The dressings of the donor area and the reconstructed area consisted of Adaptic gauze and Opsite film.

Thoracoabdominal flaps

After evaluation of the defect resulting from the mastectomy, fasciocutaneous flaps of thoracic and abdominal advancement were created. Flap size was proportional to the resulting defect and the donor area skin elasticity was the criterion for its use. After the advancement of the flap, adhesion stitches were performed with Vicryl 2.0 sutures, drainage of the dead space with a Blake drain no. 19, and closure by planes.

The dressings of the donor area and the reconstructed area consisted of Adaptic gauze and Opsite film.

The statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software version 24.0 (Chicago, IL, USA).

Differences were considered statistically significant when the p values were <0.05. The descriptive analysis was performed using frequencies and percentages for the characteristics of the various categorical variables and for obtaining measures of central tendency (average and median) for the quantitative variables.

The Kaplan-Meier method was used to evaluate patient survival.

RESULTS

We selected 11 patients with the chosen criteria (Table 1). Considering the descriptive variables, the age range was 28-63 years (mean, 49 years) and all patients were female with advanced clinical stage IIIB or IV breast cancer. The left side was the most commonly affected (6/11 patients). There were no cases of bilateral involvement.

| Patient | Age (years) | Flap | Clinical presentation | Side | Skin Metastases | Visceral Metastases | Size of lesion (cm2) | Size of Flap (cm2) | Death |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 38 | VRAM | Mass | Left | Yes | No | 240 | 200 | Yes |

| 2 | 53 | LDVY | Ulcerated mass | Right | No | Yes | 450 | 240 | Yes |

| 3 | 60 | VRAM | Mass and hyperemia | Left | No | Yes | 600 | 350 | No |

| 4 | 51 | LDVYTA | Mass and hyperemia | Left | Yes | No | 119 | 198 | No |

| 5 | 50 | LDVYTA | Ulcerated mass | Right | Yes | No | 144 | 684 | Yes |

| 6 | 42 | TA | Mass and hyperemia | Left | No | Yes | 595 | 800 | No |

| 7 | 47 | TA | Mass | Left | Yes | Yes | 63 | 800 | Yes |

| 8 | 28 | LDVY | Mass and hyperemia | Right | No | Yes | 625 | 171 | No |

| 9 | 52 | VRAM | Ulcerated mass | Right | Yes | Yes | 600 | 720 | Yes |

| 10 | 63 | TA | Ulcerated mass | Right | No | Yes | 336 | 425 | No |

| 11 | 59 | VRAM | Ulcerated mass | Left | Yes | No | 300 | 375 | Yes |

The most common tumor type was invasive ductal carcinoma (9 cases), representing 81% of the sample. The other two cases were one of invasive lobular carcinoma and one of metaplastic tumor. Of the 11 patients, four underwent a Halsted mastectomy; the others underwent modified radical mastectomy.

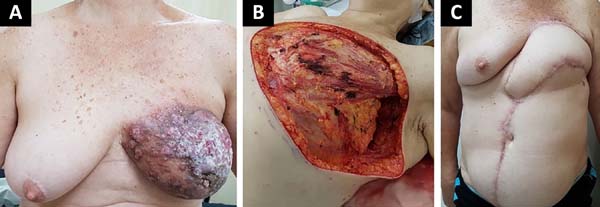

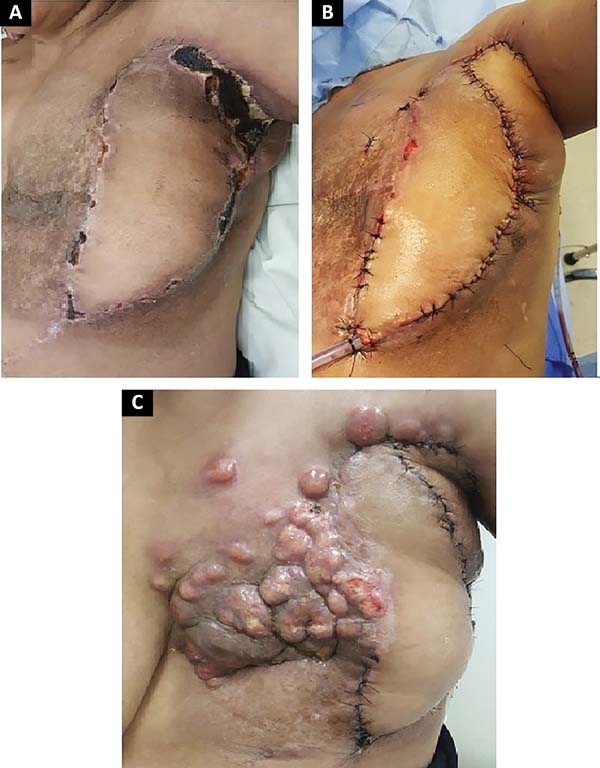

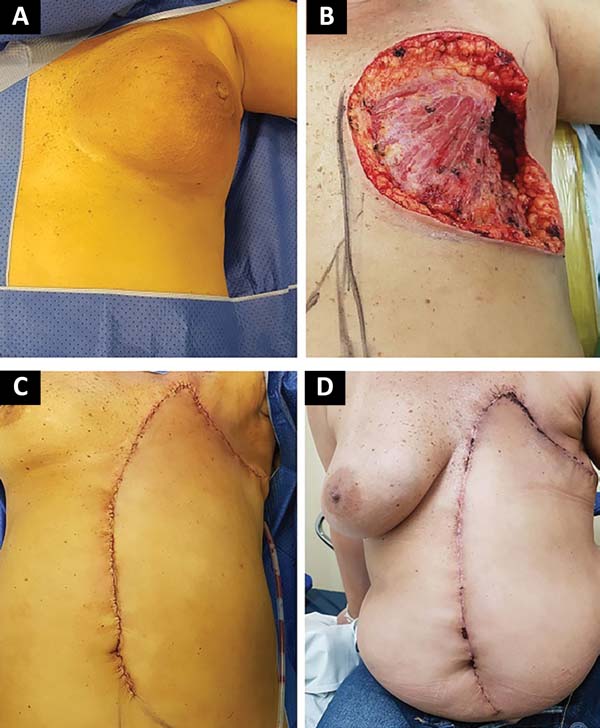

The following flaps were used: LDVY in two, LDVYTA in two (Figures 1 and 2), VRAM in four (Figures 3 and 4), and TA in three (Figure 5). The abdominal wall reinforcement mesh was used in two patients for whom the VRAM technique was selected to repair the defect. Defect sizes ranged from 17 × 7 to 45 × 10 cm (mean area, 421.72 cm2) and flap sizes ranged from 19 × 9 to 40 × 20 cm (mean area, 451 cm2).

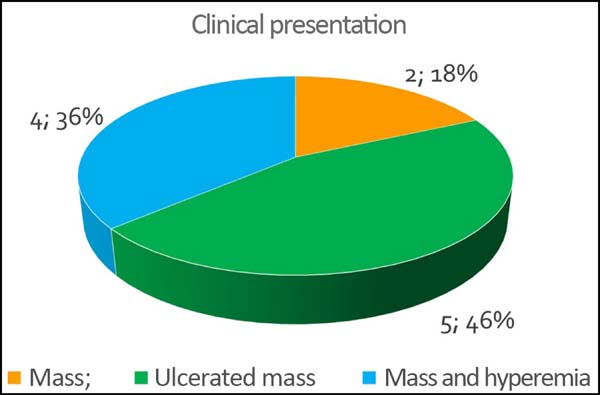

The initial clinical presentation was a massive mammary mass in two patients, mass with diffuse cutaneous hyperemia in four patients, and mass with ulceration in five patients (Figure 6). Hemorrhage was present in four of the patients, one of whom required hemostatic radiotherapy before surgery to control the symptoms.

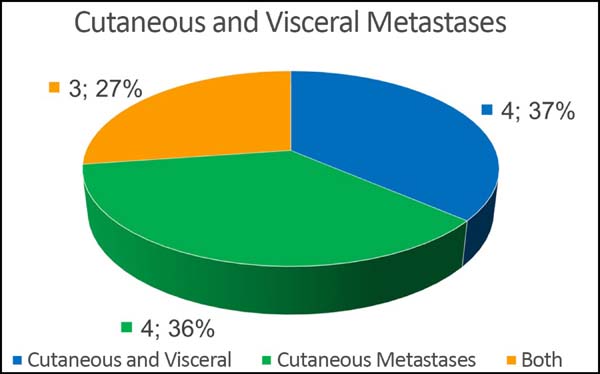

Of the 11 patients, four had cutaneous metastasis during the follow-up period, four had visceral metastases, and three had concomitant visceral and cutaneous metastases (Figure 7). Four patients previously underwent quadrantectomies and returned with recurrent disease for locoregional neoplastic control.

The mean hospitalization was 4 days (range, 1-15 days). Only one patient required postoperative follow-up in an intensive care unit (ICU) with a 1-day stay.

Four patients received complementary radiotherapy after surgical treatment. Of the 11 patients, 10 were treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy and ten patients with adjuvant chemotherapy. Of the 11 patients, three presented comorbidities: one with systemic arterial hypertension and two with associated diabetes and hypertension.

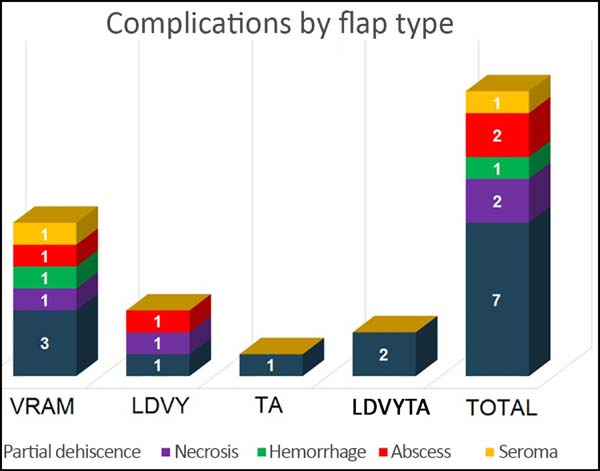

The most frequent complication was partial dehiscence (seven patients; six were managed conservatively and one required reoperation in order to enable the patient to undergo adjuvant chemotherapy), followed by epitheliolysis in three, abscess in two, and seroma in one patient (Figure 8).

A diabetic and hypertensive patient presented with a surgical wound abscess in the presence of adjuvant chemotherapy evolving to septic shock and death 32 days postoperatively. In a patient with breast cancer and previous radiotherapy who underwent reconstruction with a VRAM flap, partial necrosis of the flap and skin of the receptor area in the axillary region caused exposure of the axillary vessels. Extensive surgical debridement and local reconstruction with a fasciocutaneous parascapular flap showed a good evolution, although the patient presented locoregional recurrence of the disease 3 weeks later and died 3 months later of relapse.

At the time of data acquisition, six patients in the series had died. Of the four groups evaluated the reconstruction with a VRAM flap presented the greatest number of complications, while the thoracoabdominal flap group showed the lowest number.

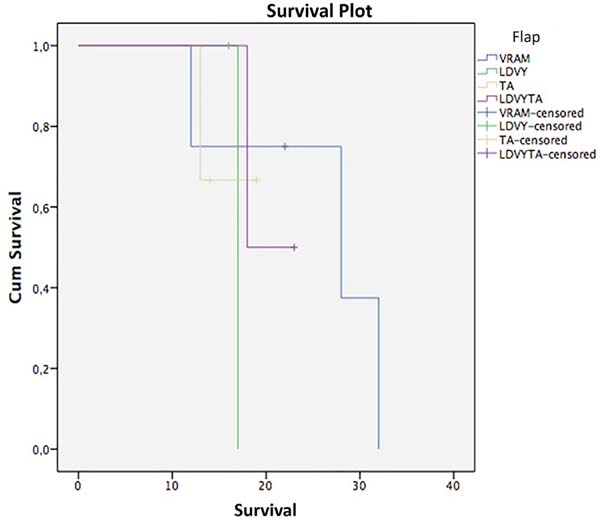

Regarding survival, the Kaplan-Meier test and stratifying by flap used resulted in the following (Figure 9, Table 2): VRAM, survival at 12 and 28 months, 75% and 37.5%; LDVYTA, 50% survival in 18 months; TA: Survival of 66.7% in 13 months. The mean survival of the VRAM flap was 25.5 months, that of LDVY flap was 17 months, that of TA was 17 months, and that of LDVYTA was 20.5 months.

| Survival Table | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cumulative Proportion | Number of Cumulative Events | Number of Remaining Cases | |||||

| Survival at the Time | |||||||

| Flap | Time (months) | Status | Estimate | Std. Error | |||

| VRAM | 1 | 12 | Yes | 0.750 | 0.217 | 1 | 3 |

| 2 | 22 | No | . | . | 1 | 2 | |

| 3 | 28 | Yes | 0.375 | 0.286 | 2 | 1 | |

| 4 | 32 | Yes | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | |

| LDVY | 1 | 16 | No | . | . | 0 | 1 |

| 2 | 17 | Yes | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| TA | 1 | 13 | Yes | 0.667 | 0.272 | 1 | 2 |

| 2 | 14 | No | . | . | 1 | 1 | |

| 3 | 19 | No | . | . | 1 | 0 | |

| LDVYTA | 1 | 18 | Yes | 0.500 | 0.354 | 1 | 1 |

| 2 | 23 | No | . | . | 1 | 0 | |

A log-rank test was applied to verify if there were statistical differences between treatment types (p = 0.87). Thus, with a significance level of 5%, there was no statistically significant survival difference among flap types.

DISCUSSION

Wide surgical resection with free margins and defect closure using myocutaneous or fasciocutaneous flaps is considered the approach of choice for locally advanced breast cancer (stages IIIB and IV). This treatment provided a free time of disease progression, improved quality of life, and increased overall survival16-28.

The LD flap plays a leading role in chest and breast reconstructions because it has a consistent vascular pedicle and a good rotational arc as a Dutra advocate. The flap was made with the patient in the lateral decubitus position, a modality that was adopted in all cases in this study29,30. In 2015, Andrade et al.31 described flap mobilization in the dorsal decubitus position and reported decreased operative time.

Due to the need for large tissue quantities to cover the defects, variations in the composition of the skin island were described as proposed by Micali et al.32 in 2001 with a skin island of an LDVY flap. Its usefulness as the first-choice flap in breast reconstructions was confirmed by Woo et al.33 in 2006, Luz et al.34 in 2010, and the present study.

Adequate patient selection, coordinated planning with a mastologist, and careful intraoperative manipulation of the involved tissues are essential to reconstruction successful reconstruction using an LDVY flap35,36. The extension of the skin outside the topography of the muscle and thus with random vascularization plays an important factor in the occurrence of complications such as dehiscence and partial necrosis. VRAM use is considered for extensive defects or when there is contraindication to LD flap use23.

Silva et al.12, in a study similar to ours, reported a resection area of 259.2 cm2, smaller than ours (421.72 cm2) which may explain the greater use of VRAM flaps in our study. In this same work, the most frequent complication was epitheliolysis, followed by partial flap necrosis.

The use of myocutaneous and fasciocutaneous flaps does not interfere in the diagnosis and treatment of a locoregional recurrence of breast cancer. In the literature, the recurrence rate was 10.6%, ranging from 2 weeks to 3.8 years20. In our study, we found a 63.3% local recurrence rate. This is attributed to the profile of the operated patients, all of whom had locally aggressive disease.

When only cutaneous metastases are present, the median survival is 42.1 months. When visceral metastases are also present, the median survival is 12.08 months37. The six patients who died had cutaneous and visceral metastasis and presented a median survival of 15 months.

CONCLUSION

Myocutaneous and fasciocutaneous flaps remain predominant choices for chest wall reconstructions and enable the extensive resections necessary to ensure oncologically adequate margins with acceptable complication rates.

COLLABORATIONS

|

JAJ |

Analysis and/or data interpretation; conception and design study; conceptualization; data curation; final manuscript approval; formal analysis; methodology; project administration; realization of operations and/or trials; supervision; visualization; writing - original draft preparation; writing - review & editing. |

|

AKD |

Supervision. |

|

MCD |

Writing - review & editing. |

|

EKY |

Writing - review & editing. |

REFERENCES

1. Bakri K, Mardini S, Evans KK, Carlsen BT, Arnold PG. Workhorse flaps in chest wall reconstruction: the pectoralis major, latissimus dorsi, and rectus abdominis flaps. Semin Plast Surg. 2011;25(1):43-54. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1055/s-0031-1275170

2. Arnold PG, Pairolero PC. Chest-wall reconstruction: an account of 500 consecutive patients. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1996;(98):804-10. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00006534-199610000-00008

3. Mansour KA, Thourani VH, Losken A, Reeves JG, Miller JI Jr, Carlson GW, et al. Chest wall resections and reconstruction: a 25-year experience. Ann Thorac Surg. 2002;73(6):1720-5. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0003-4975(02)03527-0

4. Graeber GM, Langenfeld J. Chest wall resection and reconstruction. In: Franco KL, Putman JR, eds. Advanced therapy in thoracic surgery. London: BC Decker; 1998. p. 175-85.

5. Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Instituto Nacional de Câncer José Alencar Gomes da Silva - INCA. Estimativa 2018: Síntese de Resultados e Comentários. [acesso 2018 Jan 15]. Disponível em: http://www2.inca.gov.br/wps/wcm/connect/tiposdecancer/site/home/mama/cancer_mama

6. Woodward WA, Strom EA, Tucker SL, McNeese MD, Perkins GH, Schechter NR, et al. Changes in the 2003 American Joint Committee on Cancer staging for breast cancer dramatically affect stage-specific survival. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(17):3244-8. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2003.03.052

7. National Comprehensive Cancer Network - NCCN. Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Breast Cancer. [acesso 2018 Jan 15]. Disponível em: http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/breast.pdf

8. Tansini I. Sopra il mio nuovo processo di amputazione della mammella. Gaz Med Ital. 1906;57:141.

9. Hutchins EH. A method for the prevention of elephantiasis. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1939;69:795-804.

10. Campbell DA. Reconstruction of the anterior thoracic wall. J Thorac Surg. 1950;19(3):456-61. PMID: 15406489

11. Losken A, Thourani VH, Carlson GW, Jones GE, Culbertson JH, Miller JI, et al. A reconstructive algorithm for plastic surgery following extensive chest wall resection. Br J Plast Surg. 2004;57(4):295-302. PMID: 15145731 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bjps.2004.02.004

12. Silva MMA, Sabino Neto M, Leite AT, Guimarães PAP, Ferreira LM. Reconstrução de parede torácica em extensas ressecções oncológicas. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2017;32(4):513-22.

13. Kiricuta I. L'emploi du grand épiploon dans la chirurgie du sein cancéreux. Press Med. 1963;71:15-7.

14. Tavares FM, Menezes CM, Moscozo MV, Xavier GR, Oliveira GM, Amorim Júnior MAP. Retalho de omento: uma alternativa em cirurgia reparadora da parede torácica. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2011;26(2):360-5. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1983-51752011000200028

15. Chang RR, Mehrara BJ, Hu QY, Disa JJ, Cordeiro PG. Reconstruction of complex oncologic chest wall defects: a 10- year experience. Ann Plast Surg. 2004;52(5):471-9. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.sap.0000122653.09641.f8

16. Alvarado M, Ewing CA, Elyassnia D, Foster RD, Shelley Hwang E. Surgery for palliation and treatment of advanced breast cancer. Surg Oncol. 2007;16(4):249-57. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.suronc.2007.08.007

17. Chin PL, Andersen JS, Somlo G, Chu DZ, Schwarz RE, Ellenhorn JD. Esthetic reconstruction after mastectomy for inflammatory breast cancer: is it worthwhile? J Am Coll Surg. 2000;190(3):304-9. PMID: 10703855

18. Lee MC, Newman LA. Management of patients with locally advanced breast cancer. Surg Clin North Am. 2007;87(2):379-98. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.suc.2007.01.012

19. Park JS, Ahn SH, Son BH, Kim EK. Using local flaps in a chest wall reconstruction after mastectomy for locally advanced breast cancer. Arch Plast Surg. 2015;42(3):288-94. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5999/aps.2015.42.3.288

20. Slavin SA, Love SM, Goldwyn RM. Recurrent breast cancer following immediate reconstruction with myocutaneous flaps. Plast Recons Surg. 1994;93(6):1191-204. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00006534-199405000-00013

21. Tanabe M, Iwase T, Okumura Y, Yoshida A, Masuda N, Nakatsukasa K, et al.; Collaborative Study Group of Scientific Research of the Japanese Breast Cancer Society. Local recurrence risk after previous salvage mastectomy. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2016;42(7):980-5. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ejso.2016.03.008

22. Cagli B, Barone M, Ippolito E, Cogliandro A, Silipigni S, Ramella S, et al. Ten years experience with breast reconstruction after salvage mastectomy in previously irradiated patients: analysis of outcomes, satisfaction and well-being. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2016;20(22):4635-41.

23. Rao R, Feng L, Kuerer HM, Singletary SE, Bedrosian I, Hunt KK, et al. Timing of surgical intervention for the intact primary in stage IV breast cancer patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15(6):1696-702. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1245/s10434-008-9830-4

24. Blanchard DK, Shetty PB, Hilsenbeck SG, Elledge RM. Association of surgery with improved survival in stage IV breast cancer patients. Ann Surg. 2008;247(5):732-8. PMID: 18438108 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181656d32

25. Graziosi GB, Lucas FAS, Maximiano AMC, Caiado Neto BR, Prota Júnior MLC. Reconstrução de parede torácica em tumores de mama localmente avançados. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2013;28(3 Suppl.1):64.

26. Franco D, Tavares Filho JM, Cardoso P, Moreto Filho L, Reis MC, Boasquevisque CHR, et al. A cirurgia plástica na reconstrução da parede torácica: aspectos relevantes - série de casos. Rev Col Bras Cir. 2015;42(6):366-37. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/0100-69912015006003

27. Batista KT, Araujo HJ, Mammare EM, Aita AA, Silva RS. Reconstrução da parede torácica após a ressecção de extensos tumores. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2014;29(4):550-6.

28. Novoa N, Benito P, Jiménez MF, de Juan A, Luis Aranda J, Varela G. Reconstruction of chest wall defects after resection of large neoplasms: ten-year experience. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2005;4(3):250-5. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1510/icvts.2004.103432

29. Dutra AK, Neto MS, Garcia EB, Veiga DF, Netto MM, Curado JH, et al. Patients' satisfaction with immediate breast reconstruction with a latissimus dorsi musculocutaneous flap. J Plast Surg Hand Surg. 2012;46(5):349-53. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/2000656X.2012.704726

30. Dutra AK, Sabino Neto M, Garcia EB, Veiga DF, Domingues MC, Yoshimatsu EK, et al. The role of transverse latissimus dorsi musculocutaneous flap immediate breast reconstruction. Eur J Plast Surg. 2009;32(6):293-9. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00238-009-0366-z

31. Andrade FAG, Duarte FG, Chaves LO, Bezerra RN, Salvador Filho LHA, Silva SVD. A sistematização do retalho do músculo latíssimo do dorso em decúbito dorsal. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2015;30(2):190-6.

32. Micali E, Carramaschi FR. Extended V-Y latissimus dorsi musculocutaneous flap for anterior chest wall reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;107(6):1382-90. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00006534-200105000-00010

33. Woo E, Tan BK, Koong HN, Yeo A, Chan MY, Song C. Use of the extended V-Y latissimus dorsi myocutaneous flap for chest wall reconstruction in locally advanced breast cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;82(2):752-5. PMID: 16863813 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.athoracsur.2005.07.030

34. Luz DP, Lobo CAH, Hiraki P, Okada A, Montag E, Ferreira MC. Retalho miocutâneo de latíssimo do dorso em V-Y para reconstrução de grandes defeitos torácicos extensos. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2010;25(3 Suppl.1):64.

35. Munhoz AM, Montag E, Arruda E, Okada A, Brasil JA, Gemperli R, et al. Immediate locally advanced breast cancer and chest wall reconstruction: surgical planning and reconstruction strategies with extended V-Y latissimus dorsi myocutaneous flap. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;127(6):2186-97. PMID: 21617452 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0b013e318213a038

36. Marcondes CA, Pessoa SGDP, Pessoa BBGD, Dias IS, Ribeiro NP Estratégias em reconstruções de tórax pós-ressecções extensas de tumores de mama localmente avançados: uma série de 11 casos. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2015;30(3):339-44.

37. Hu SC, Chen GS, Lu YW, Wu CS, Lan CC. Cutaneous metastases from different internal malignancies: a clinical and prognostic appraisal. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22(6):735-40. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-3083.2008.02590.x

1. A. C. Camargo Cancer Center, Núcleo de Cirurgia

Plástica Reparadora, São Paulo, SP, Brazil.

Corresponding author: Joel Abdala Junior, Rua Prof. Antônio Prudente, nº 211 - Liberdade, São Paulo, SP, Brazil, Zip Code 01509-010. E-mail: drjoelabdala@gmail.com

Article received: July 31, 2018.

Article accepted: November 11, 2018.

Conflicts of interest: none.

Read in Portuguese

Read in Portuguese

Read in English

Read in English

PDF PT

PDF PT

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to Cite

How to Cite

Mendeley

Mendeley

Pocket

Pocket

Twitter

Twitter