Case Report - Year 2018 - Volume 33 -

Pregnancy and burns: experience of a university hospital burn unit

Gestação e queimadura: experiência de unidade de queimaduras em Hospital Universitário

ABSTRACT

Introduction: The incidence of burns involving pregnant

women is not well established in the literature, but is

estimated to be between 3% and 7%. The management

of burns in pregnancy represents a great challenge with

significant impact on outcomes and maternal-fetal prognosis.

Case Report: In the present study, we report two cases of

pregnant burn victims who were treated in the burn unit in

the Paulista School of Medicine, Federal University of São

Paulo (EPM/UNIFESP). One patient was treated in the first

trimester and the other in the third trimester.

Conclusion:

In both cases, the pregnant women received specialized

treatment for burns in conjunction with clinical follow-up

by the obstetrics team, with good maternal-fetal outcomes.

Keywords: Burns; Burns unit; Pregnancy; High-risk pregnancy

RESUMO

Introdução: A incidência de queimaduras em gestantes não é bem estabelecida na literatura

mundial, mas estima-se que varie entre 3% e 7%. Os cuidados da gestante

queimada representam um grande desafio com impacto significante nos

resultados e prognóstico materno-fetais.

Relato de Caso: No presente estudo relatamos dois casos de gestantes vítimas de queimaduras

que foram tratadas na unidade de tratamento de queimaduras na Escola

Paulista de Medicina da Universidade Federal de São Paulo (EPM/UNIFESP), uma

no primeiro trimestre e a outra no terceiro trimestre.

Conclusão: Em ambos os casos, as gestantes receberam tratamento especializado para

queimaduras em conjunto com acompanhamento clínico da equipe da obstetrícia,

com boa evolução materno-fetal.

Palavras-chave: Queimaduras; Unidades de queimados; Gravidez; Gravidez de alto risco

INTRODUCTION

Burns during pregnancy require greater care due to associated physiological changes. The incidence of burns during pregnancy is not well established in the literature, but is estimated to range between 3% and 7%, and primarily reflects the incidence in developing countries1,2. The management of burns in pregnancy represents a great challenge, with significant impact on maternal-fetal prognosis. We report two cases treated in the burn unit of the Paulista School of Medicine, Federal University of São Paulo (EPM/UNIFESP), in São Paulo, SP.

CASE REPORTS

Clinical case 1

A 36-year-old, previously healthy woman sustained accidental burns caused by a flaming alcoholic liquid. She was injured in the 10th week of gestation, with body surface area involvement of 29%. She had 2nd and 3rd degree burns on the face, chest, abdomen, arms, hands, and legs bilaterally. She underwent tracheal intubation on admission for respiratory insufficiency secondary to likely inhalation injury, which was later confirmed with bronchoscopy.

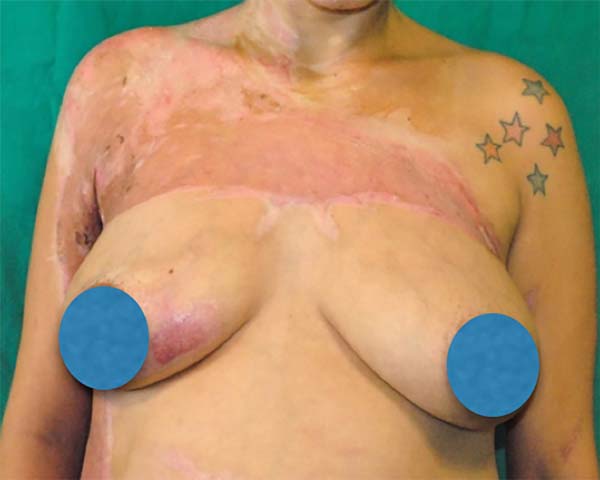

During hospitalization, she underwent debridement and grafting of burned areas with success. The obstetrics team was involved in her care and ultrasound confirmed the gestational age. The patient was discharged from the hospital after completion of burn treatment and was referred for outpatient obstetric follow-up until full-term birth (Figures 1, 2, 3, and 4).

Clinical case 2

A 29-year-old woman was the victim of aggression by her partner at 31 weeks of gestation, with burns caused by a flaming alcoholic liquid. She had 2nd and 3rd degree burns on 15% of the body surface, involving the face, neck, anterior trunk, and right upper limb.

During hospitalization, she underwent debridement and grafting of burned areas with success. Cardiotocography was performed by the obstetrics team to monitor fetal viability. She was discharged from the burn unit and transferred to the obstetrics unit, where she remained hospitalized until full-term birth (Figures 5, 6, 7, and 8).

DISCUSSION

The percentage of body surface area (BSA) involvement is the main prognostic factor for maternal and fetal mortality, with 50% mortality when involved BSA is >40%1. Inhalation injury is another important prognostic factor related to maternal and fetal mortality3-5. The most common complication is fetal distress, followed by spontaneous abortion and preterm labor3,4.

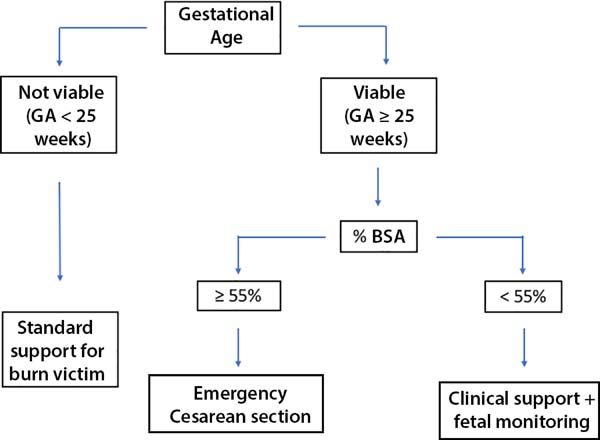

Proper treatment is essential for success and survival of the fetus. On initial assessment, the maternal BSA and gestational age (GA) of the fetus should be calculated, preferably by ultrasound, to confirm fetal viability. In 2015, Parikh et al.1 published an algorithm designed to assist in the management of pregnant burn victims (Figure 9).

Pregnant patients with more than 55% BSA involvement should undergo urgent cesarean section if the fetus is viable, as this significantly improves maternal and fetal prognosis. In cases with less than 55% BSA involvement, resuscitation and support measures should continue, with continuous fetal monitoring and use of corticosteroids to induce fetal lung maturation if needed1.

Hypovolemia is a major challenge in the treatment of burns in general. There is no guideline for fluid resuscitation in pregnant burn patients, but in general, the Parkland formula is used; the formula recommends an increase in fluid replacement by 30%, due to the physiological increase in intravascular volume during gestation1,2. In pregnancy, hypovolemia may have direct implications for the progress of gestation6. Fluid loss after a burn can trigger premature labor2.

Another source of vulnerability in pregnant burn victims is the upper airway1,6. Physiological edema that is already present in the upper airways during pregnancy can accelerate airway obstruction in cases of inhalation injury and can interfere with intubation1,5.

The first clinical case describes treatment in the first trimester of pregnancy, in which the medications used most influenced decision-making. The medications commonly used for the treatment of burns were evaluated for safe use in the first trimester. In the second clinical case, the risk of premature labor due to the stress of trauma and surgery was the main determinant in management.

Chemical prophylaxis of deep venous thrombosis is strongly recommended because of the hypercoagulable state of pregnancy. Low-molecular-weight heparin was used in the first case, and unfractionated heparin in the second, both of which are considered safe for use in pregnancy1. The use of proton-pump inhibitors or H2 inhibitors is also considered safe and recommended for pregnant women due to the risk of gastric peptic ulcer.

In both cases, ranitidine1 was chosen. Of the antimicrobials usually used in the treatment of burns, amikacin is known to be teratogenic and its use should be avoided in the treatment of pregnant women, even in topical form1.

Early grafting, preferably before 48 hours, has been shown to reduce maternal mortality, without negatively impact on survival of the fetus7. For this reason, when the conditions of the pregnant patient and fetus allow, we should not delay surgical procedures, and both intraoperative and postoperative care require special attention7.

Fetal heart rate monitoring using ultrasound is recommended in the intraoperative and immediate postoperative period, starting at 16 weeks, with continuous cardiotocography starting at 25 weeks8. Fetal Doppler ultrasound on admission and 2 weeks after the injury is recommended, due to the risk of late fetal death6,9.

CONCLUSION

The reported cases illustrate the treatment of burns during two distinct phases of pregnancy, i.e., at the beginning of pregnancy and approaching term. In the first trimester, special attention should be given to the medications that will be used during treatment, due to the risk of teratogenicity.

In the third trimester, fetal monitoring with cardiotocography is more important due to the risk of fetal distress, abortion, and premature delivery. Given the unique features of pregnancy, the complexity of burn treatment is apparent. Although burns are best managed by prevention, greater knowledge of the physiology of gestation allows us to properly manage burns in pregnancy.

COLLABORATIONS

|

JRNLF |

Analysis and/or interpretation of data; statistical analyses; final approval of the manuscript; conception and design of the study; writing the manuscript or critical review of its contents; special supplement (article submitter). |

|

ELF |

Analysis and/or interpretation of data; completion of surgeries and/or experiments; writing the manuscript or critical review of its contents. |

|

GFT |

Analysis and/or interpretation of data; final approval of the manuscript; conception and design of the study; writing the manuscript or critical review of its contents. |

|

AFO |

Analysis and/or interpretation of data; final approval of the manuscript; conception and design of the study; writing the manuscript or critical review of its contents. |

|

LMF |

Analysis and/or interpretation of data; statistical analyses; final approval of the manuscript; conception and design of the study; completion of surgeries and/or experiments; writing the manuscript or critical review of its contents. |

REFERENCES

1. Parikh P, Sunesara I, Lutz E, Kolb J, Sawardecker S, Martin JN Jr. Burns During Pregnancy: Implications for Maternal-Perinatal Providers and Guidelines for Practice. Obstet Ginecol Surv. 2015;70(10):633-43. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/OGX.0000000000000219

2. Akhtar MA, Mulawkar PM, Kulkarni HR. Burns in pregnancy: effect on maternal and fetal outcomes. Burns. 1994;20(4):351-5. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0305-4179(94)90066-3

3. Karimi H, Momeni M, Momeni M, Rahbar H. Burn injuries during pregnancy in Iran. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2009;104:132-4. PMID: 19022440 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2008.10.003

4. Maghsoudi H, Smnia R, Garadaghi A, Kianvar H. Burns in Pregnancy. Burns. 2006;32(2):246-50. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.burns.2005.10.003

5. Roderique EJ, Gebre-Giorgis AA, Stewart DH, Feldman MJ, Pozez AL. Smoke inhalation injury in a pregnant patient: a literature review of the evidence and current best practices in the setting of a classic case. J Burn Care Res. 2012;33(5):624-33. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/BCR.0b013e31824799d2

6. Jain V, Chari R, Maslovitz S, Farine D; Maternal Fetal Medicine Committee, Bujold E, et al. Guidelines for the Management of a Pregnant Trauma Patient. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2015;37(6):553-74. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1701-2163(15)30232-2

7. Prasanna M, Singh K. Early burn wound excision in major burns with pregnancy: a preliminary report. Burns. 1996;22(3):234-7. PMID: 8726266 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0305-4179(95)00113-1

8. Vilas Boas WW, Lucena MR, Ribeiro RC. Anestesia para cirurgia não-obstétrica durante a gravidez. Rev Med Minas Gerais. 2009;19(3 Supl 1):S70-S79.

9. Einarson A, Bailey B, Inocencion G, Ormond K, Koren G. Accidental electric shock in pregnancy: a prospective cohort study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;176(3):678-81. PMID: 9077628 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0002-9378(97)70569-6

1. Universidade Federal de São Paulo, Escola

Paulista de Medicina, São Paulo, SP, Brazil.

Corresponding author: Andrea Fernandes de Oliveira, Rua Napoleão de Barros, 737 - 14º andar, Vila Clementino - São Paulo, SP, Brazil. Zip Code 04024-002. E-mail: dra.afo@gmail.com

Article received: September 24, 2017.

Article accepted: September 5, 2018.

Conflicts of interest: none.

Read in Portuguese

Read in Portuguese

Read in English

Read in English

PDF PT

PDF PT

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to Cite

How to Cite

Mendeley

Mendeley

Pocket

Pocket

Twitter

Twitter