Case Report - Year 2018 - Volume 33 -

Case Report: Klippel-Trénaunay-Weber syndrome

Relato de caso: síndrome de Klippel-Trénaunay-Weber

ABSTRACT

Introduction: The Klippel-Trénaunay-Weber syndrome

(KTWS) is characterized by several signs, including capillary

malformations and venous malformations with or without

lymphatic malformations associated with limb overgrowth. In

most cases, only one extremity is involved with arteriovenous

malformation, and approximately 75% of the patients manifest

symptoms before 10 years of age.

Case Report: We report a case

of a 7-month-old patient with KTWS followed-up at the Plastic

Surgery Service of the Hospital de Clínicas, Federal University of

Uberlândia; surgical treatment of the lesion was proposed for the

patient.

Conclusion: Since KTWS is a progressive disease with

severe morbidity, the patient must be followed-up at a reference

center by experienced staff with diverse therapeutic arsenal.

Keywords: Klippel-Trénaunay-Weber syndrome; Vascular malformations; Hemangioma

RESUMO

Introdução: A síndrome de Klippel-Trénaunay-Weber (SKTW) é caracterizada pelo conjunto de

sinais que consiste em malformações capilares, malformações venosas com ou

sem malformações linfáticas associado ao supercrescimento de membros. Na

maioria das vezes, envolve apenas uma extremidade com malformação

arteriovenosa e cerca de 75% dos pacientes manifestam antes dos 10 anos de

idade.

Relato de Caso: Relatamos um caso de Klippel-Trénaunay-Weber em um paciente de 7 meses em

acompanhamento na enfermaria da Cirurgia Plástica do Hospital de Clínicas da

Universidade Federal de Uberlândia para o qual foi proposto tratamento

cirúrgico da lesão.

Conclusão: Como a SKTW é uma doença com morbidade progressiva e grave, o paciente deve

ser acompanhado em um centro de referência com experiência e arsenal

terapêutico diversificado para atuar da melhor forma possível no

tratamento.

Palavras-chave: Síndrome de Klippel-Trenaunay-Weber; Malformações vasculares; Hemangioma

INTRODUCTION

Klippel-Trénaunay-Weber syndrome (KTWS) is characterized by a set of signs that consist of capillary malformations, venous malformations with or without lymphatic malformations associated with limb overgrowth1. In most cases, it involves only one extremity with arteriovenous malformation and approximately 75% of patients manifest the disease before 10 years of age2,3.

Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome was first described by Maurice Klippel and Paul Trenaunay. They reported two cases that had the triad (port wine stain, varices and bone and soft tissue hypertrophy) in common4. Some time later, Frederick Weber described some cases presenting a similarity to the triad, with the presence of arteriovenous fistula as an association3,4. SKTW and Parkes Weber’s Syndrome may be considered together as Klippel-Trenaunay-Weber sd because they present different clinical signs of a single disease5,6.

KTWS is a rare congenital mesodermal disorder, with about 1000 cases recorded worldwide7. KTWS is distributed equally among the various ethnic groups and affects more men, at a ratio of 1.5:17,8. The etiology of this syndrome remains unknown, although there are some theories of its pathogenesis9.

Although KTWS is a sporadic condition, studies have reported familial cases of KTWS that were not inherited through a Mendelian pattern, suggesting a multifactorial inheritance, with variable penetration and expression. Subsequent studies conducted by Happle suggest that the inheritance of a single defective gene acquired during embryogenesis could explain the development of this syndrome, as well as the occurrence of sporadic and familial cases, suggesting that an autosomal dominant inheritance is most likely10,11.

Clinically, KTWS comprises flat hemangioma, venous changes such as malformations and varicose veins, and bone and soft tissue hypertrophy. 12,13

The diagnosis is clinical and can be performed by the presence of the triad of abnormalities, or only two signs of the triad.

Usually, the patients with port wine stains, from birth, mainly in hypertrophied limbs, varying in depth14. Venous malformations affect the lower limbs in the vast majority of cases. Arterial or venous angiodysplasia may be present in any region of the body, from the skin to the visceral organs. Therefore, there is the possibility of phlebitis, bleeding, deep venous thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, hemoperitoneum, hemothorax and chronic venous insufficiency15.

It is a rare syndrome, but deserves to be highlighted due to progressive and severe morbidity.

CASE REPORT

D.A.P., 7 months old, male, born and resident in Anápolis-GO, was forwarded to our service in the Emergency Room of the Hospital de Clínicas, Federal University of Uberlândia, MG, on 12/29/2014 with fever, vomiting, diarrhea and dehydration for 2 days. Together with this presentation, he presented a giant hemangioma in the left lower limb, varicose veins and hypertrophy of bone and soft tissues (KTWS) (Figure 1) with a history of recent laser treatment in another service of Goiânia-GO and with propranolol.

The patient progressed rapidly and severely with necrosis of the left lower limb (LLL) up to the ipsilateral gluteal region and with refractory septic shock (Figure 2). He received intensive ICU treatment with vasopressor drugs and broad spectrum antibiotic therapy for 28 days. Arterial and venous echo Doppler was performed during assessment of vascular surgery, confirming the diagnosis of Klippel-Trénaunay-Weber syndrome and identifying arteriovenous malformation and small fistulas of the left limb. However, extensive necrotic lesion in the LLL remained, requiring, primarily, surgical debridement of the LLL and subsequently left hip disarticulation with protective colostomy on 01/28/2015.

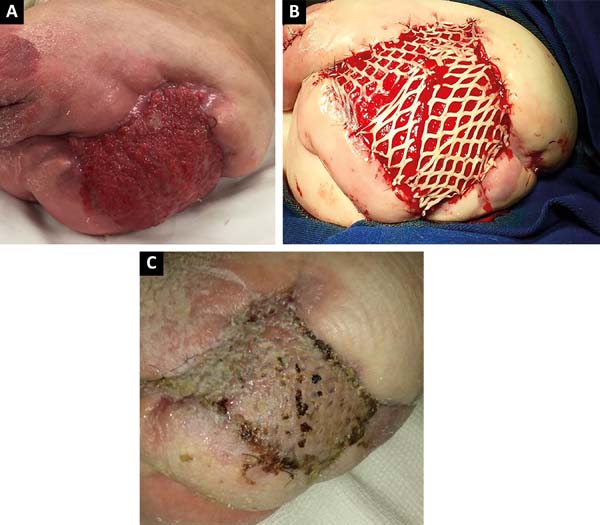

After 2 months of intensive clinical treatment, clinical and topical improvement of the lesion was observed in the postoperative region of the disarticulation(Figure 3A), and skin grafting was performed with electric dermatome and Mash Graft for occlusion of the bloody wound (Figure 3B), with the donor area of the right thigh. The patient presented good clinical recovery and epithelialization of the recipient and donor area, being discharged on the 15th postoperative day(Figure 3C).

The patient has been in outpatient follow up in this service, progressing satisfactorily with complete epithelialization of the donor and recipient areas. The protective colostomy has been closed with the reconstruction of the intestinal transit.

DISCUSSION

This study was motivated by having received a patient referring prior treatment in another Plastic Surgery service with conservative treatment of KTWS with laser. Such conduct maintained the patient incapacitated, suffering with symptoms of chronic venous stasis and evolved with complications of local skin infection until receiving the final treatment.

There is no curative treatment, and the therapeutic goals are intended to improve the patient’s symptoms and correcting the consequences of serious injuries and length discrepancy. However, all authors agree that conservative measures continue to guide the treatment of KTWS. This does not rule out the need for timely surgical interventions during the evolution of the natural history of the disease.

Adjuvant therapies can vary from laser therapy, with microfoam sclerotherapy, staged resections of ectatic veins and even larger excisions1,16-19 . The most commonly used indications for surgical treatment are: hemorrhage, local infections, thromboembolism and the occurrence of very refractory leg ulcers. Other indications are: local pain, functional limitations and aesthetics17.

Interventional radiotherapy plays a major role in the propaedeutics of arteriovenous malformations (AVMs). Through it, one can evaluate the type of malformation and how the feeding vessels are structured. For the treatment of low flow AVM (KTWS), in some cases an injection of sclerosing agent may be applied to make the vessels smaller.

In other cases, this can be done using fluoroscopy. There are limited options for treatment of congenital venous dysplasia. In severe cases, the interventionist can use surgical removal, sclerotherapy or an endovascular ablation technique. If there are symptoms in the skin, such as Port wine stains, laser treatment may be indicated.

In cases such as the one described, considering the treatment performed, the area covered by grafting can be seen as a good reconstructive option, taking into account the simplicity of the procedure, less morbidity when compared to the use of flaps and the possibility of rehabilitation through the use of prostheses.

Despite being the highest level of lower limb amputation, the prosthesis is efficient, since the prosthesis for this level of amputation provides security and stability, with continuous gait, with or without locomotion aids, depending on other factors including the age of the patient.

KTWS should be suspected in all newborns with capillary malformations involving one extremity of the body from birth. The differential diagnosis for KTWS is Proteus syndrome and Maffucci syndrome, among other non-syndromic capillary malformations20.

Major advances will be made when it is possible to diagnose KTWS even more early and prevent the development of tissue hypertrophy, complex angiodysplasias and other phenotypic changes, perhaps by correcting or preventing the related genetic mutation20.

CONCLUSION

KTWS is a rare disease, with progressive and severe morbidity. The patient with this syndrome must be accompanied in a reference center with experience and a diverse therapeutic arsenal to act in the best possible way in the treatment. Each patient has the parsimony and individualization in choosing the best treatment, as well as the ideal time to accomplish it.

Currently, the indication for surgical intervention is restricted to the complications arising from the initial presentation. In this case, the use of surgical treatment was crucial to allow an improvement in clinical condition and quality of life of the patient, showing that it can be a valid alternative.

REFERENCES

1. Villela ALC, Guedes LGS, Paschoa VVA, David AB, Tenório TM, Lamego Junior HP, et al. Perfil epidemiológico de 58 portadores de síndrome de Klippel-Trénaunay-Weber acompanhados no Ambulatório da Santa Casa de São Paulo. J Vasc Bras. 2009;8(3):219-24. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1677-54492009000300006

2. Favorito LA. Vesical Hemangioma in patient with Klippel-Trenaunay-Weber syndrome. J Urol. 2003;29(2):149-50.

3. Tonsgard JH, Fasullo M, Windle ML, McGovern M, Petry PD, Buehler B. Klippel-Trenaunay-Weber Syndrome [Internet]. Pediatrics: General Medicine Articles 2006. Disponível em: http://www.emedicine.com/derm/topic213.htm

4. Klippel M, Trénaunay P. Du naevus variqueux osteohypertrophique. Arch Gen Med (Paris). 1900;185:641-72.

5. Weber FP. Haemangiectatic hypertrophy of limbs: congenital phlebarteriectasis and so-called congenital varicose veins. Br J Child Dis. 1918;15:13-7.

6. Kihiczak GG, Meine JG, Schwartz RA, Janniger CK. Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome: a multisystem disorder possibly resulting from a pathogenic gene for vascular and tissue overgrowth. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45(8):883-90. PMID: 16911369 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-4632.2006.02940.x

7. Berry SA, Peterson C, Mize W, Bloom K, Zachary C, Blasco P, et al. Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome. Am J Med Genet. 1998;79(4):319-26. PMID: 9781914 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1096-8628(19981002)79:4<319::AID-AJMG15>3.0.CO;2-U

8. Capraro PA, Fisher J, Hammond DC, Grossman JA. Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;109(6):2052-60; quiz 2061-2. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00006534-200205000-00041

9. Meine JG, Schwartz RA, Janniger CK. Klippel-Trenaunay-Weber syndrome. Cutis. 1997;60(3):127-32. PMID: 9314616

10. Lorda-Sanchez I, Prieto L, Rodriguez-Pinilla E, Martinez-Frias ML. Increased parental age and number of pregnancies in Klippel-Trenaunay-Weber syndrome. Ann Hum Genet. 1998;62(Pt 3):235-9. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1469-1809.1998.6230235.x

11. Hergesell K, Kröger K, Petruschkat S, Santosa F, Herborn C, Rudofsky G. Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome and pregnancy. Int Angiol. 2003;22(2):194-8.

12. Wang QK. Update on the molecular genetics of vascular anomalies. Lymphat Res Biol. 2005;3(4):226-33. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1089/lrb.2005.3.226

13. Delis KT, Gloviczki P, Wennberg PW, Rooke TW, Driscoll DJ. Hemodynamic impairment, venous segmental disease, and clinical severity scoring in limbs with Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome. J Vasc Surg. 2007;45(3):561-7. PMID: 17275246 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jvs.2006.11.032

14. Viljoen D, Saxe N, Pearn J, Beighton P. The cutaneous manifestations of the Klippel-Trenaunay-Weber syndrome. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1987;12(1):12-7. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2230.1987.tb01845.x

15. Kihiczak GG, Meine JG, Schwartz RA, Janniger CK. Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome: a multisystem disorder possibly resulting from a pathogenic gene for vascular and tissue overgrowth. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45(8):883-90. PMID: 16911369 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-4632.2006.02940.x

16. Lindenauer SM. The Klippel-Trenaunay Syndrome: Varicosity, Hypertrophy and Hemangioma With No Arteriovenous Fistula. Ann Surg. 1965;162(2):303-4. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00000658-196508000-00023

17. Gloviczki P, Driscoll DJ. Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome: current management. Phlebology. 2007;22(6):291-8. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1258/026835507782655209

18. Frasier K, Giangola G, Rosen R, Ginat DT. Endovascular radiofrequency ablation: a novel treatment of venous insufficiency in Klippel-Trenaunay patients. J Vasc Surg. 2008;47(6):1339-45. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jvs.2008.01.040

19. Delis KT, Gloviczki P, Wennberg PW, Rooke TW, Driscoll DJ. Hemodynamic impairment, venous segmental disease, and clinical severity scoring in limbs with Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome. J Vasc Surg. 2007;45(3):561-7. PMID: 17275246 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jvs.2006.11.032

20. Garzon MC, Huang JT, Enjolras O, Frieden IJ. Vascular malformations. Part II: associated syndromes. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56(4):541-64. PMID: 17367610

1. Universidade Federal de Uberlândia, Uberlândia,

MG, Brazil.

Corresponding author: Victor Parreira Bizinoto, Av. Mato Grosso, nº 3395, apt. 202 - Umuarama - Uberlândia, MG, Brazil. Zip Code 38405-314. E-mail: victorpbizinoto@hotmail.com

Article received: November 26, 2017.

Article accepted: September 5, 2018.

Conflicts of interest: none.

Read in Portuguese

Read in Portuguese

Read in English

Read in English

PDF PT

PDF PT

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to Cite

How to Cite

Mendeley

Mendeley

Pocket

Pocket

Twitter

Twitter