Original Article - Year 2018 - Volume 33 -

Analysis of the evolution of burn patients based on their epidemiological profile in Santa Casa de Misericórdia de Santos, Brazil

Análise da evolução dos pacientes queimados de acordo com seu perfil epidemiológico na Santa Casa de Misericórdia de Santos, Brasil

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Burns are an important public health problem,

representing the second cause of death in childhood not only

in the United States but also in Brazil. However, available data

and information for guiding prevention programs are limited.

The objective of this study was to analyze the epidemiological

data of hospitalized patients diagnosed with burns and to

outline a profile of the patients in the study period.

Methods:

A retrospective study of the 716 hospitalized patients from

January 2011 to May 2017 at Santa Casa de Misericórdia

de Santos (SCMS) for Plastic Surgery was performed. The

demographic profile, length of hospital stay, and mortality were

analyzed.

Results: Of the 716 hospitalized patients, the mean

age was 29 years in both sexes, and 28 patients, with a mean

age of 58.6 years, died during the study period.

Conclusion:

The study showed the profile of hospitalized patients in SCMS

and the importance of care in burn patients. All factors of poor

prognosis were determined, and older age was considered an

important factor for the unfavorable progression of the cases.

Keywords: Burns; Burn units; Analytical epidemiology; Health public policy

RESUMO

Introdução: As queimaduras constituem um importante problema de saúde pública,

representando a segunda causa de morte na infância não só nos Estados Unidos

como também no Brasil. Porém, existem poucos dados e informações disponíveis

para orientar programas de prevenção. O objetivo do trabalho foi de analisar

dados epidemiológicos de pacientes com o diagnóstico de queimadura

internados traçando um perfil dos pacientes no período estudado.

Método: Estudo retrospectivo dos 716 pacientes internados no período de janeiro de

2011 a maio de 2017 na Santa Casa de Misericórdia de Santos (SCMS) para a

especialidade de Cirurgia Plástica. Foram analisados o perfil demográfico,

tempo de internação e mortalidade.

Resultados: Dos 716 pacientes internados, a média de idade total é de 29 anos em ambos

sexos e nesse período 28 foram a óbito, com média de idade de 58,6 anos.

Conclusão: O estudo mostrou o perfil dos pacientes internados na SCMS e a importância

dos cuidados com os pacientes queimados e todos os fatores de mau

prognóstico, como a idade mais avançada, que se colocou como um importante

fator para a evolução desfavorável dos casos.

Palavras-chave: Queimaduras; Unidades de queimados; Epidemiologia analítica; Políticas públicas de saúde

INTRODUCTION

In Brazil, burns are estimated to occur in 1,000,000 individuals annually, with no sex, age, race, or social class restriction, with strong economic impact due to prolonged treatment and follow-up1,2.

Patients with severe burns are more likely to die because of septicemia due to massive release of inflammatory mediators in addition to the difficulty of tissue diffusion of antimicrobials due to vessel thrombosis and tissue necrosis. However, other parameters are also closely related to mortality3.

In the mid-1990s, 50% to 80% of patients with burns involving >50% of total body surface area (BSA) died because of sepsis, shock, and multiple organ failure. Currently, >90% of these patients present favorable progression4,5.

This improvement in progression is because of improved care, new treatment techniques, advances in patient management, greater number of doctors, and specialized centers.

However, despite all improvements, the management of elderly burn patients still presents as a major challenge. In contrast to low hospitalization rates, elderly patients have a high mortality rate. The association of diseases, medicalization, and deterioration of cognitive capacity makes elderly patients more susceptible to complications that result in death6-8.

As age increases, the risk of death significantly increases with the increase in the extent of burns. Based on the data from the National Burn Repository 2011 of the American Burn Association (Canada, United States, and Sweden), for burns between 20% and 30% of burned body surface (BBS), the mortality rate is approximately 1% in the of 2-5 years age group, whereas the mortality rate is approximately 35% in the 70-80 years age group. For more extensive burns, between 60% and 70% of BBS, the mortality rate is approximately 10% in the 2-5 years age group, whereas the mortality rate is approximately 85% in the 70-80 years age group9.

In a study conducted on the expenditures of the Unified Health System (SUS), burns treated at a non-specialized hospital corresponded to the highest cost-day (cost-day = value paid for hospitalizations/number of days of stay), amounting to R$ 130.18.

The high cost and shortage of specialized burn centers in Brazil show that, regardless of age, in cases requiring hospitalization, adequate and specialized care to the patient in the acute phase play a crucial role in reducing mortality, functional, aesthetic, and psychological sequelae10-12.

OBJECTIVE

To analyze the evolution of the patients hospitalized in Santa Casa de Misericórdia de Santos, in Santos, SP; trace an epidemiological profile; and conduct a retrospective study in order to analyze the risk factors for the death of these patients, mainly focusing on age and sex as contributing factors for the outcome.

METHODS

Retrospective study of patients hospitalized in SCMS from January 2011 to May 2017. Analysis of sex, age, length of hospital stay, and mortality.

RESULTS

In the analyzed period of 6 years and 5 months in SCMS, the plastic surgery service had 716 hospitalizations, wherein patients who received only primary care and were not hospitalized were not accounted for in the study.

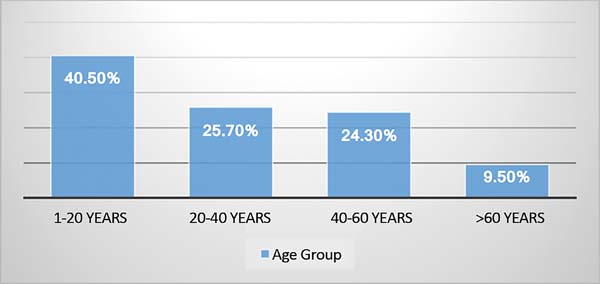

The profile of hospitalized patients based on age varied from 1 to 97 years, and the age group of 20 years had the highest prevalence of cases (40.5%); in the age group of 20-40 years, 184 (25.6%); among patients aged 40-60 years, 174 (24.3%) had only 68 (9.4%) patients (Figure 1).

In relation to sex, 276 (38.54%) and 440 (61.45%) were women and men, respectively, with a mean age of 29 years for both sexes (Figure 2).

In the analysis of the general mortality of the patients, 28 deaths were noted, with a total percentage of 3.91%. However, in the analysis of only patients aged 60 years or older, the percentage of death increased to 36.34%, although these patients were in the lowest age group among hospitalized patients. This shows that age and all comorbidities that are associated are important factors for worsening the outcome of burn patients (Table 1).

| Sex | Burns | Deaths | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Women | 276 | 16 | 5.79 |

| Men | 440 | 12 | 2.72 |

| Total | 716 | 28 | 3.91 |

| Elderly people (>60 years) | 38 | 14 | 36.34 |

Based on the study, the length of hospital stay in both sexes varied, with a mean of 21 days, with 24.9 male patients older than 60 years (Table 2).

| Sex | Mean age | Length of Hospital Stay |

|---|---|---|

| Women | 29.9 | 21.33 |

| Men | 29.1 | 21.8 |

| Elderly people aged >60 years | ||

| Women | 73.6 | 20.3 |

| Men | 70.5 | 24.9 |

DISCUSSION

This retrospective study showed the epidemiological profile, tracing the demographic profile data and characteristics of age, sex, and length of hospital stay. The indices collected showed the characteristics already reported in the literature. With these data collected, it is possible to draw care plans for patients hospitalized in SCMS, seeking to improve care by identifying poor prognostic factors, such as BSAs, etiology, secondary injuries with inhalation, and associated pathologies inherent in patients, preventing sequelae whenever possible, and by identifying infections leading to a worse case outcome. Other criteria cannot be treated, such as age, but data demonstrating its importance can be identified by conducting and determining more effective treatment measures (Figure 3).

CONCLUSION

In the study period, 716 patients were hospitalized due to burns, with a greater number of male patients. However, the deaths were higher in women. Age was a worse prognostic factor, as shown by the death rate in patients older than 60 years, being >10 times the mean of patients affected.

A slight downward trend was shown in hospital admissions, but it was not sufficient to demonstrate the need for more investment in public education strategies in order to combat burn accidents.

In this way, the data presented are extremely important to identify the epidemiological profile of the populations most affected and the circumstances wherein burns occur and may demonstrate the preventive measures for public health.

REFERENCES

1. Rocha HJS, Lira SVG, Abreu RNDC, Xavier EP, Viera LJES. Perfil dos acidentes por líquidos aquecidos em crianças atendidas em centro de referência de Fortaleza. Rev Bras Prom Saúde. 2007;20(2):86-91. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5020/18061230.2007.p86

2. Fracanoli TS, Magalhães FL, Guimarães LM, Serra MCVF. Estudo transversal de 1273 pacientes internados no centro de tratamento de queimados do Hospital do Andaraí de 1997 a 2006. Rev Bras Queimaduras. 2007;7(1):33-7.

3. Farina Jr JA, Almeida CEF, Barros MEPM, Martinez R. Redução da mortalidade em pacientes queimados. Rev Bras Queimaduras. 2014;13(1):2-5.

4. Merrell SW, Saffle JR, Sullivan JJ, Larsen CM, Warden GD. Increased survival after major thermal injury: a nine year review. Am J Surg. 1987;154(6):623-7. PMID: 3425806 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0002-9610(87)90229-7

5. Herndon DN, Gore D, Cole M, Desai MH, Linares H, Abston S, et al. Determinants of mortality in pediatrics patients with greater than 70% full-thickness total body surface area thermal injury treated by early total excision and grafting. J Trauma. 1987;27(2):208-12.

6. Oliveira DS, Leonardi DF. Sequelas físicas em pacientes pediátricos que sofreram queimaduras. Rev Bras Queimaduras. 2012;11(4):234-9.

7. Solanki NS, Greenwood JE, Mackie IP, Kavanagh S, Penhall R. Social issues prolong elderly burn patient hospitalization. J Burn Care Res. 2011;32(3):387-91. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/BCR.0b013e318217f90a

8. Duke J, Wood F, Semmens J, Edgar DW, Spilsbury K, Willis A, et al. Rates of hospitalisations and mortality of older adults admitted with burn injuries in Western Australian from 1983 to 2008. Australas J Ageing. 2012;31(2):83-9. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6612.2011.00542.x

9. American Burn Association (ABA). 2011 National Burn Repository. Report of data from 2001-2010 [Internet]. 2011 [cited 2012 Jun 27]. Available from: http://www.ameriburn.org/2011NBRAnnualReport.pdf

10. Melione LPR, Mello-Jorge MHP. Gastos do Sistema Único de Saúde com internações por causas externas em São José dos Campos, São Paulo, Brasil. Cad Saúde Pública. 2008;24(8):1814-24. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0102-311X2008000800010

11. Ferreira E, Lucas R, Rossi LA, Andrade D. Curativo do paciente queimado: uma revisão de literatura. Rev Esc Enferm USP. 2003;37(1):44-51. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0080-62342003000100006

12. Soares de Macedo JL, Santos JB. Nosocomial infections in a Brazilian Burn Unit. Burns. 2006;32(4):477-81. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.burns.2005.11.012

1. Santa Casa de Misericórdia de Santos, Santos,

SP, Brazil.

2. Sociedade Brasileira de Cirurgia Plástica, São

Paulo, SP, Brazil.

Corresponding author: Rodolfo Toscano Zafani, Rua João Pinho, nº 27, apt. 41 - Boqueirão - Santos, SP, Brazil. Zip Code 11055-060. E-mail: rodzafani@hotmail.com

Article received: January 13, 2018.

Article accepted: May 17, 2018.

Conflicts of interest: none.

Read in Portuguese

Read in Portuguese

Read in English

Read in English

PDF PT

PDF PT

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to Cite

How to Cite

Mendeley

Mendeley

Pocket

Pocket

Twitter

Twitter