Original Article - Year 2018 - Volume 33 -

Omphaloplasty: Y/V technique

Onfaloplastia: técnica Y/V

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Omphaloplasty is a crucial procedure during

abdominoplasty surgery. Although it is currently considered an

important step, omphaloplasty was not always performed during

abdominoplasties, and the umbilicus was sometimes discarded

together with the fat flap. Various techniques were used to

preserve the umbilicus and underwent modifications with time

to allow for an increasingly natural result.

Method: The proposed

"Y"/"V" technique consists of modeling the umbilical stump to

perfectly fit in the same place where the umbilicus was located.

The umbilical island, after being modeled, is sutured, resulting

in a "Y"/ "V" image, which gives rise to the name.

Results: A

low number of complications (11.34%) were observed when

analyzing the postoperative follow-up data. Suture dehiscence,

umbilical stenosis, color alterations in the scar, and keloid

scars were the complications observed, which were surgically

corrected six months postoperatively.

Conclusion: The proposed

technique is simple to implement, with low rates of complications

and results in a more natural aspect of the neoumbilicus

scar. Further studies are required to prove its effectiveness in

comparison to the other techniques that are currently in use.

Keywords: Abdominoplasty; Reconstructive surgical procedures; Umbilicus

RESUMO

Introdução: A onfaloplastia é um momento crucial durante a cirurgia de abdominoplastia.

Apesar de ser considerada uma etapa de grande importância nos dias de hoje,

a onfaloplastia não foi sempre utilizada nas abdominoplastias, sendo o

umbigo, algumas vezes, descartado junto ao retalho gorduroso. Com a

finalidade de preservar a cicatriz umbilical, várias técnicas foram

utilizadas e, com o tempo, vêm sofrendo modificações que possibilitam um

resultado cada vez mais natural.

Método: A técnica "Y"/"V" proposta consiste em modelar o coto umbilical de modo que

este encaixe perfeitamente no mesmo local onde havia a cicatriz umbilical. A

ilha umbilical, após ser modelada, é suturada, resultando em uma imagem de

"Y"/"V", razão pela qual a técnica recebe este nome.

Resultados: Durante o estudo, foi evidenciado um número baixo de complicações (11,34%) ao

analisar o pós-operatório. Deiscência de sutura, estenose umbilical,

alterações crômicas na cicatriz e queloide foram as complicações observadas,

sendo corrigidas cirurgicamente seis meses após a cirurgia.

Conclusão: A técnica proposta demonstra simples execução, com baixos índices de

complicações e aspecto mais natural da cicatriz do neoumbigo. Portanto,

tornam-se cada vez mais necessários estudos que a utilizem para comprovar

sua eficácia perante às demais técnicas utilizadas atualmente.

Palavras-chave: Abdominoplastia; Procedimentos cirúrgicos reconstrutivos; Umbigo

INTRODUCTION

Abdominoplasty is a type of plastic surgery that is carried out for essentially aesthetic purposes. In recent years, it has become a common procedure among women who desire to improve their body image, self-esteem, mental health, sexual relations, and quality of life. One of the most important steps in this surgical procedure is the reconstruction of the umbilicus.

The characteristics of the umbilicus include a depressed scar surrounded by skin folds, located in the anterior abdominal wall, approximately 18-23 cm from the vulvar commissure, 4 cm above and 2 cm below the horizontal line that passes by the two anterior superior iliac spines1. The umbilicus has an elliptical shape in the vertical direction, or T-shape with a longitudinal axis that passes vertically in the midline. The mean diameter of the umbilical cord ranges from 1.5 to 2 cm, with a conical depression whose vertex is attached to the anterior muscular wall of the abdomen2.

Anatomical studies performed by Dick in 19703 showed four fibrous cords connected to the umbilical surface, which are responsible for the displacement of the umbilicus in the posterior direction. These fibrous structures originate from traces of the umbilical vein, the urachus, and the two umbilical arteries.

The umbilicus is the only natural scar on the body, and is therefore an important and essential aesthetic component of the abdomen. Given that customs and fashion increasingly stimulate the exposure of the abdomen, the secondary umbilical scar of dermolipectomy is a frequent concern of surgeons and patients.

The concern with aesthetics, however, does not coincide with the development of abdominoplasty. In the 19th century in France, some techniques removed the umbilicus alongwith the abdominal flap4. Weinhold Zentralb, in 1909, was the first to retain the umbilicus during abdominal dermolipectomy5.

In 1924, First performed the first umbilical transposition. Since then, many geometric shapes were attempted to obtain a scar that was close to the natural shape of the umbilicus. In 1931, Flesch-Thebesius and Weisheimer preserved a skin triangle in the umbilicus6,7. Prudente, in 19438, and Andrews, in 19569, performed a transposition through circular incisions, leaving it in a skin cylinder. In 1957, Vernon10, also using a transposition of circular forms observed many stenoses at the umbilicus, which became challenging.

In 1979, Avelar11 presented his technique wherein multiple “Vs” shaped incisions were made on the inner face of the umbilicus, breaking the scar into three flaps. In this sense, other Brazilian authors, such as López-Tallaj & Gervais, in 2001, Saldanha et al., in 2003, D’Assumpção, in 2005, and Mello & Yoshino in 200912-15, also proposed the use of various geometric shapes in search of the “ideal umbilicus”.

Since the introduction of classic abdominoplasty, the umbilicus is preserved in its original position and is refixed through a hole in the abdominal flap. Even with the advancement of many techniques, the umbilicus continues to be fixed in the same manner.

In modern abdominoplasty, several forms have been created, with respect to both the umbilical scar and the cutaneous flap opening, with the sole objective of obtaining a result that resembles the natural umbilicus. Round, oval, drop-shaped, triangular forms with upper or lower base, and lozenges have been proposed. However, they all have a scar that surrounds the entire perimeter of the umbilicus16,17.

OBJECTIVE

To minimize the unsightly scarring effects associated with omphaloplasty, we propose the use of a technique that has demonstrated positive operative results and results in a more natural scar and with a lower rate of postoperative complications.

METHOD

In this study, 88 female patients between 27 and 62 years of age, with a mean age of 43 years, underwent surgery using the “Y”/“V” technique between June 2012 and May 2015.

Our marking was performed with the patient in an upright position, the midline being marked in the preoperative period and reinforced after asepsis of the patient and the operative region to prevent possible lateral displacement of the neoumbilicus (Figure 1).

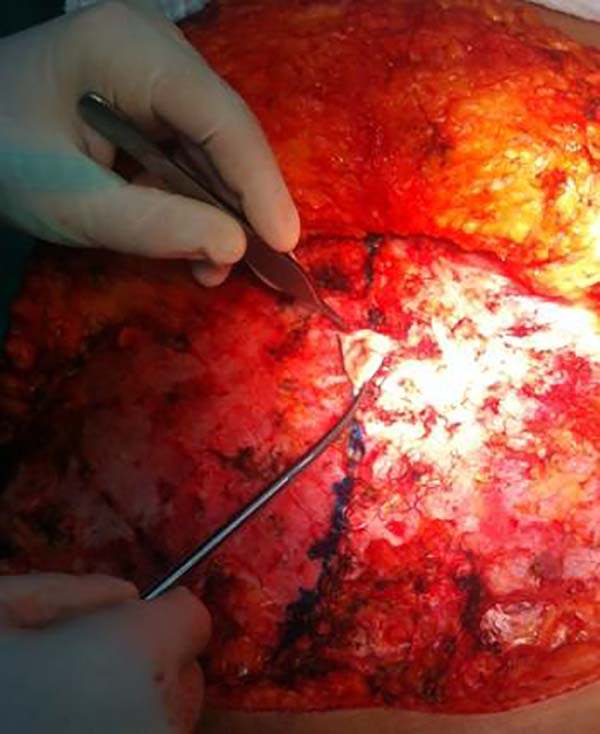

All procedures were performed after epidural and intravenous sedation administered by the team anesthesiologist. After asepsis, the surgery began with the use of a no. 15 scalpel blade on the skin and was followed by the detachment of the abdominal flap with an electric scalpel. The detachment extends up to the umbilicus, with the umbilicus being isolated with a round-shaped scalpel blade no. 15 (Figure 2).

After isolation of the umbilicus, we continue with the elevation above the umbilicus up to the xiphoid appendix, forming a tunnel without extending this detachment laterally to prevent vascularization problems of the flap. After completing the detachment, we raise the head of the patient and evaluate the amount of the flap that will be resected based on the previous marking. Once the flap is removed, and plication of the rectus abdominis is performed, we specifically perform the proposed technique.

The fixation of the umbilical stump is performed with separate sutures in the aponeurosis of the rectus abdominis muscles, being evaluated based on its mobility based on the thickness of the panniculus resulting from the definitive abdominal flap (Figure 3). The rounded resected umbilical island is modeled with curved scissors to attain a “Y” shape, with the removal of a skin triangle in the cephalic portion and rectified on its right and left sides to form a “Y” (Figures 4 and 5).

After fixing the abdominal flap in the lower scar, marking the location of the neoumbilicus in the abdominal skin flap is held in the form of “Y,” by using a maneuver that introduces the hand by the lateral opening of the flap, where, by contiguity, the umbilicus is palpated, and this is projected into the skin after the introduction of a 25 × 7 needle in the direction of the index finger of the surgeon, which is on the umbilical island fixed to the aponeurosis, without which the surgeon can be injured (Figure 6).

This point is marked on the lower portion of the surgeon’s finger. After this first point, a new marking is made with methylene blue at a distance of 1.0 to 1.5 cm in the middle line above point 1 (depending on the thickness of the panniculus and the width of the patient to avoid large or small neoumbilicus on the patient’s abdomen). Thereafter, two lateral and superior points are marked between 0.5 and 1.0 cm of point 2, thus forming the “Y” proposed in this technique (Figure 7).

At this point, the skin is incised on top of the “Y” marking (Figure 8), and a fat cylinder is removed from the already fixed abdominal flap (Figure 9). To prevent umbilical stenosis, two “slivers” of the lateral flaps of the Y are removed to accommodate the umbilical suture better (Figure 10).

The umbilical suture begins with the triangular skin flap, formed by the incision in “Y” next to the vertex of the “V” removed on the umbilical island, allowing the descent of this flap and upper intraumbilical accommodation, which provides the concealment of the scar at this level (Figure 11). Subsequently, the bottom vertex of the umbilical island is fixed to the bottom vertex of the “Y” incised in the abdominal flap. Two lateral sutures are held next to the upper lateral vertices of the umbilical island and the lateral sides of the “Y” incised in the skin (Figure 12).

After these four pillars of fixation, the suture is completed with two more sutures at each side and two sutures between the initial triangular flap and the lateral vertices of the Y. 4-0 colorless nylon sutures are used.

Finally, with respect to the neoumbilicus, there is an open Y-shape, with its triangular caudal part and the cephalic part embedded within the panniculus of the abdominal flap, which provides more aesthetics to the neoumbilicus and a reduction in abdominoplasty stigma with a more apparent and sutured umbilicus (Figure 13).

Finally, wound dressing was performed using neomycin and the introduction of a ball-shaped gauze, which was replaced by a silicone umbilical mold after 48 h after surgery. The umbilical sutures are removed after 7 days, and the condition of scar is observed at this time.

RESULTS

A significant decrease in cases of umbilical stenosis was demonstrated in patients who underwent surgery in our study compared to the incidence noted with circular, oval, and other techniques. Additionally, a more natural shape is observed compared to an abdomen without a scar(Figures 14 to 19).

Complications include suture dehiscence in three cases, wherein we observed that, in these patients, the panniculus was denser (3.4%), umbilical stenosis developed in 1 patient (1.13%), color changes in the scar occurred in 4 patients (4.54%), keloid scars developed in 2 patients (2.27%), which were surgically corrected after 6 months.

Altogether, 11.34% of patients experienced complications; thus, we conclude that the technique was efficient and reduced umbilical scarring, requiring constant studies and adaptations to prevent the complications noted above.

It is important to note that a thorough physical examination and a good indication for surgery will lead to better results, considering all the factors involved during surgery.

DISCUSSION

There are several techniques for the construction of the neoumbilicus. The main techniques used are a circular shape, “V” shape and other designs proposed by several authors. To date, in our experience, the more harmonious and natural results, from the aesthetic point of view, are obtained with non-circular designs because they result in less stenosis of the umbilical scar.

Our proposed technique is easy to perform, with good aesthetic results, and a more natural postoperative abdomen after dermolipectomy with regard to the acceptance by patients of the resulting umbilical scar.

The final open Y format is closer to the natural aspect of an abdomen that has not been operated on.

Other authors perform neo-omphaloplasties in non-circular forms, with satisfactory results in relation to the aesthetic natural look of the neoumbilicus.

CONCLUSION

The technique reported in this study is a good alternative to other techniques used in the treatment of the neoumbilicus. Long-term monitoring and increasing the number of cases will be important in evaluating the technique and defining its use.

This proposed technique is simple to implement, providing a better long-term aspect of the umbilicus, with improved natural results and prevents frequent stenoses of the umbilicus that occurs with techniques that attempt to achieve a round-shape. It was called “Y” due to the shape of the incision on the skin of the abdominal flap for the formation of the neoumbilicus.

We suggest its use after the analysis of these cases, which proved to be satisfactory for both the surgeon and the patients who submitted to abdominal dermolipectomy, thus increasing the technical and tactical arsenal of the clinical surgeon.

COLLABORATIONS

|

VHMG |

Analysis and/or interpretation of data; statistical analyses; final approval of the manuscript; conception and design of the study; completion of surgeries and/or experiments; writing the manuscript or critical review of its contents. |

|

VAG |

Analysis and/or interpretation of data; statistical analyses; final approval of the manuscript; writing the manuscript or critical review of its contents. |

|

FAG |

Analysis and/or interpretation of data; statistical analyses; final approval of the manuscript; writing the manuscript or critical review of its contents. |

|

PCCCJ |

Analysis and/or interpretation of data; statistical analyses; final approval of the manuscript; conception and design of the study; writing the manuscript or critical review of its contents. |

REFERENCES

1. Ng JAA. Abdominoplastias: neo-onfaloplastia sem cicatriz e sem excisão de gordura. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2010;25(3):499-503. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1983-51752010000300017

2. Parnia R, Ghorbani L, Sepehrvand N, Hatami S, Bazargan-Hejazi S. Determining anatomical position of the umbilicus in Iranian girls, and providing quantitative indices and formula to determine neo-umbilicus during abdominoplasty. Indian J Plast Surg. 2012;45(1):94-6. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.4103/0970-0358.96594

3. Dick ET. Umbilicoplasty as a treatment for persistent umbilical infection. Aust N Z J Surg. 1970;39(4):380-3. PMID: 5269347 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1445-2197.1970.tb05377.x

4. Hakme F. Abdominoplasty: peri and supra-umbilical lipectomy. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 1983;7(4):213-20. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF01570662

5. Thorek. Plastic surgery of the breast and abdominal wall. Springfield: Thomas; 1942.

6. Sinder R. Cirurgia plástica do abdome. Rio de Janeiro: Ramil Sinder; 1979.

7. Franco T, Rebello C. Cirurgia estética. Rio de Janeiro: Atheneu; 1977.

8. Prudente A. Dermolipectomia abdominal com conservação da cicatriz umbilical. Anais do II Congresso Latino-Americano de Cirurgia Plástica. Buenos Aires: Guilherme Karast; 1943. 468 p.

9. Andrews JM. Nova técnica de lipectomia abdominal e onfaloplastia. Memória do 8o Congresso Latino-Americano de Cirurgia Plástica. Cuba; 1956.

10. Vernon S. Umbilical transplantation upward and abdominal contouring in lipectomy. Am J Surg. 1957;94(3):490-2. PMID: 13458618 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0002-9610(57)90807-3

11. Avelar JM. Cicatriz umbilical: da sua importância e da técnica de confecção nas abdominoplastias. Rev Bras Cir. 1979;69(1/2):41-52.

12. López-Tallaj L, Gervais J. Restauração Umbilical na Abdominoplastia: Uma Simples Técnica Retangular. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2001;16(3):39-46.

13. D'Assumpção EA. Técnica Para Umbilicoplastia, Evitando-se um dos Principais Estigmas das Abdominoplastias. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2005;20(3):160-6.

14. Mello DF, Yoshino H. Plicatura da base umbilical: proposta técnica para tratar protrusões e evitar estigmas pós-abdominoplastia. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2009;24(4):525-9.

15. Saldanha OR, De Souza Pinto EB, Mattos WN Jr, Pazetti CE, Lopes Bello EM, Rojas Y, et al. Lipoabdominoplasty with selective and safe undermining. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2003;27(4):322-7. PMID: 15058559 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00266-003-3016-z

16. Pitanguy I. Abdominal lipectomy: an approach to it through an analysis of 300 consecutive cases. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1967;40(4):384-91. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00006534-196710000-00012

17. Silva FN, Oliveira EA. Neo-onfaloplastia na abdominoplastia vertical. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2010;25(2):330-6.

1. Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Belo

Horizonte, MG, Brazil.

2. Hospital Mater Dei, Belo Horizonte, MG,

Brazil.

3. Sociedade Brasileira de Cirurgia Plástica, São

Paulo, SP, Brazil.

4. Clínica MC Médicos, Montes Claros, MG, Brazil.

5. Faculdades Integradas Pitágoras, Montes Claros,

MG, Brazil.

Corresponding author: Fernando de Azevedo Gonçalves, Avenida Aida Mainartina, nº 100 - Ed. Veneza, Apto 105 - Ibituruna, Montes Claros, MG, Brazil. Zip Code 39408-007. E-mail: feazegoncalves@gmail.com

Article received: October 31, 2016.

Article accepted: June 22, 2018.

Conflicts of interest: none.

Read in Portuguese

Read in Portuguese

Read in English

Read in English

PDF PT

PDF PT

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to Cite

How to Cite

Mendeley

Mendeley

Pocket

Pocket

Twitter

Twitter