Original Article - Year 2018 - Volume 33 -

Combined Otoplasty

Otoplastia Combinada

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Protruding ear is the most common congenital deformity of the head and neck,

with an autosomal dominant inheritance and no predilection for sex.

Protruding ear or prominent ear occurs when there is concha excess or

hypertrophy, erasure of the antihelix, a scapho-conchal angle greater than

90º, or a combination of these factors, occurring uni- or bilaterally. The

objective is to present a conservative approach to correct protruding ear,

with a combination of techniques.

Methods: The otoplasty surgical technique involved an anterior approach for resection

of the auricular concha, which was associated with weakening of the

antihelix, and partial incisions of the cartilage were performed through

anterior access and of Mustardé sutures, through posterior access for better

definition of the antihelix without fixation of the concha to the mastoid.

Two hundred patients with a mean age of 17 years underwent operations

between January 1987 and January 2015, 60% of whom were female.

Results: Of the 200 patients, only 24 patients needed discrete surgical revisions.

Conclusion: The surgical procedure is simple, easily reproducible, provides good results,

and is associated with a high degree of satisfaction and a low rate of

complications/morbidities.

Keywords: Reconstructive surgical procedures; External ear; Pinna/abnormalities; Hypertrophy

RESUMO

Introdução: Orelha em abano é a deformidade congênita mais comum de cabeça e pescoço,

cuja transmissão se dá por herança autossômica dominante, sem predileção por

gênero. A orelha proeminente ou "em abano" ocorre quando há um excesso ou

hipertrofia da concha auricular, apagamento da antélice, um ângulo

escafoconchal maior que 90º ou uma combinação destes, ocorrendo uni ou

bilateralmente. O objetivo é apresentar uma abordagem conservadora para

correção de orelha em abano, com a associação de técnicas.

Métodos: Foi utilizada uma variação cirúrgica para realização de otoplastia com o

auxílio de uma abordagem anterior para ressecção da concha auricular

associada ao enfraquecimento da antélice com incisões parciais na cartilagem

também por via anterior e a realização de pontos de Mustardé por via

posterior para melhor definição da antélice, sem a fixação da concha à

mastoide. Foram operados 200 pacientes com idade média de 17 anos, entre

janeiro de 1987 e janeiro de 2015, sendo 60% do gênero feminino.

Resultados: Dos 200 pacientes, apenas 24 necessitaram revisões cirúrgicas discretas.

Conclusão: O procedimento cirúrgico é simples, facilmente reprodutível, proporcionando

bons resultados, com alto grau de satisfação e baixo índice de

complicações/morbidade.

Palavras-chave: Procedimentos cirúrgicos reconstrutivos; Orelha externa; Pavilhão auricular/anormalidades; Hipertrofia

INTRODUCTION

Protruding ear is the most common congenital deformity of the head and neck, with a 5% incidence in Caucasians1. This disorder is transmitted by an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern, generally occurs between the 12th and the 16th week of gestation, and has no apparent sex predilection. Diagnosis is performed at birth in 61% of patients2.

In 1903, Morestin3described the posterior access method, which became the standard of that time, and popularized conchal cartilage hypertrophy as the cause of pinna prominence.

William Henry Luckett4, in 1910, introduced the important concept of restoration of the antihelix.

In 1952, Becker5 introduced the concept of conical antihelix, which involved combining the incision and suture of the cartilage in an attempt to soften the external contour. This technique was refined by Converse et al.6 in 1955 and Converse & Wood-Smith7 in 1963.

Gibson & Davis8, in 1958, demonstrated that the cartilage can bend away on the opposite side, when one side is partially sectioned.

Stenström9, in 1963, using this principle, proposed a technique to provide a more natural form to the antihelix through multiple superficial abrasions on the anterior surface of the auricular cartilage, to form a new convexity of the antihelix.

Mustardé10,11, in 1963, introduced his suture technique, which created the antihelix through permanent sutures between the concha and the scapha, providing a soft format to the antihelix.

In 1967, Kayne12 created the first of several combined techniques, which combined the previous Stenström abrasion with the posterior Mustardé suture.

Furnas13, in 1968, introduced a technique to correct prominent ears with the use of sutures between the concha and the mastoid. In 1969, this technique was modified by Spira et al.14.

In 1990, Elliot15 proposed a procedure to reduce the concha when the posterior suture (Furnas) alone was insufficient for correcting the position of the ear. To do this, an anterior incision is used at the edge of the concha, the incised cartilage edges are sutured, and the excess skin in the region is not resected. He was the first to describe the combined access.

Spina and Stahl, in 1983, used only cartilage resection to correct protruding ears, and the excess skin in the anterior region was not sectioned13.

In 1997, Hell et al.16 described cartilage resection by a posterior access technique.

Advances in otoplasty have made it possible not only to fix the ears posteriorly but also to improve their shape, reduce their size, and render them more symmetrical.

OBJECTIVE

The objective of this work is to introduce an approach for the correction of protruding ears, using a combination of techniques.

METHODS

A surgical variation was used to perform otoplasty that included an anterior approach to resect the auricular concha, which was associated with weakening of the antihelix. Our method also involved anterior access with partial incisions, and Mustardé sutures were accomplished by posterior access to better define the antihelix, without fixation of the concha to the mastoid.

All the patients who were analyzed were operated upon by the same surgeon with the described technique. The patients who were included had prominent ears (Tanzer Classification V of congenital ear deformities). Two hundred patients, with a mean age of 17 years, were operated upon bilaterally, between January 1987 and January 2015. Of the included patients, 60% were females.

Surgical technique

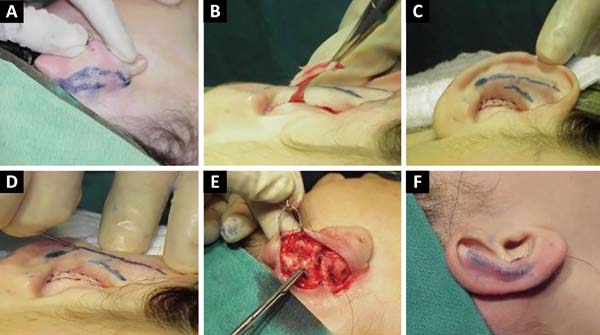

The antihelix was marked with methylene blue, which showed the crus that needed to be weakened. The hypertrophy of the concha was removed through anterior access. A skin spindle approximately 0.5 cm wide and 4-5 cm wide was marked in the vicinity of the posterior auricular sulcus.

The ear was infiltrated with standard epinephrine solution (1:200,000), in the region of the retroauricular spindle and in the anterior region of the concha.

A spindle resection of the skin was performed with wide detachment in the proximity of the posterior auricular sulcus (Figure 1A). An incision and resection of the skin spindle (3-4 mm) was performed in the anterior region of the concha, and the excess conchal cartilage was also resected in the spindle in its innermost region. (Figure 1B). The anterior incision was sutured with a 6-0 nylon monofilament (Figure 1C). In addition, in the anterior region, the weak antihelix cartilage was held with the cutting edge of a 30 × 7 mm needle, with the use of at least three partial incisions. The sutures were applied with the bevel of the needle, parallel to the antihelix without piercing the cartilage, in order to weaken the cartilage and facilitate the Mustardé sutures and the anticipated curvature of the antihelix (Figure 1D).

Next, Mustardé (three or four) sutures were held with 5-0 nylon monofilament to recompose the anatomy of the antihelix, without fixing it to the mastoid (Figure 1E).

Skin syntheses were held with an intradermal suture of 5-0 nylon monofilament, without tension in the suture (Figure 1F).

Dressing in the immediate postoperative period was performed with gauze and bandages, with a crepe bandage. On the first postoperative day, the dressing that was performed on the previous day was removed and cartilage modeling, with small strips of micropore, was held together, with the approximation of the ear and the mastoid. This type of dressing was maintained for 15 days, with weekly replacements that were performed by the surgeon.

RESULTS

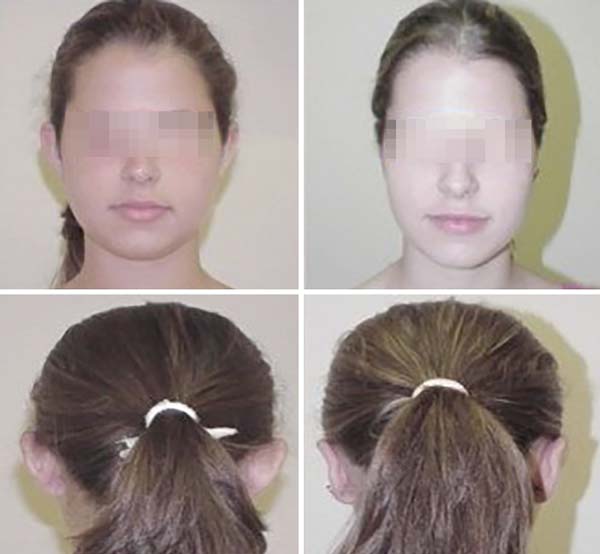

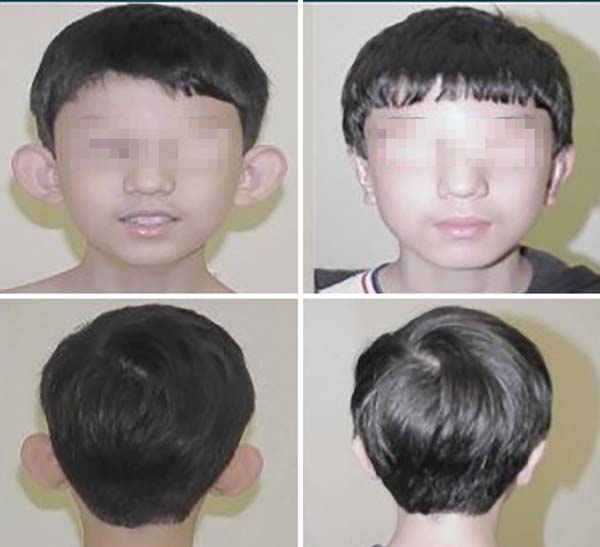

The operative results were effective in almost all cases, with marked improvement in the shape of the ear. Scars were minimal and were disguised in the anterior curvature of the concha, and the majority of patients were satisfied with the procedure (Figures 2 and 3).

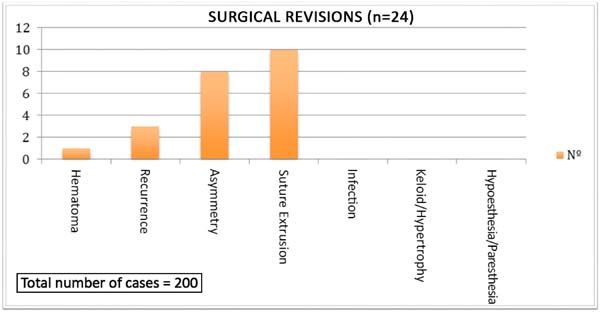

There was one case of a small hematoma, which was drained in the first postoperative day, without consequences. Surgical revisions were performed in five cases of unilateral recurrence in the upper portion of the helix, which were corrected with re-suture of the Mustardé sutures, and in eight patients who exhibited asymmetry. The complications and revisions can be observed in Figure 4 and in Table 1. There were no cases of hypertrophic scars or keloid or surgical re-approaches in all of the complications mentioned in Figure 4 and in Table 1.

| Complications | Nº | % |

|---|---|---|

| Hematoma | 1 | 0.1 |

| Recurrence | 5 | 3.5 |

| Asymmetry | 8 | 4.0 |

| Infection | 0 | 0 |

| Suture Extrusion | 10 | 5.0 |

| Keloid/Hypertrophy | 0 | 0 |

| Hypoesthesia/Paresthesia | 0 | 0 |

The number of suture extrusions was in accordance with the literature (3% to 6%).

Throughout the study period, the surgical technique presented similar results. The figures that accompany the text illustrate the described technique (Figure 1A-F).

DISCUSSION

Protruding ear is the most common ear deformity. This deformity can be noticed at birth and usually becomes more pronounced with time1, and its incidence is approximately 5% in Caucasians2. Although not entailing functional alterations, ear deformities can cause major psychosocial disorders17. Protruding ears is determined by one or a set of anatomical changes; thus, appropriate surgical planning should individually consider the deformities of each part of the ear 17.

Two angle measurements are changed in protruding ears: the cephalo-auricle and the scapho- conchal angles. The cephalo-auricle angle represents the distance between the ear and the skull; normally, it measures between 20º and 30º and is considered borderline up to 45º or a distance of between 1.8 and 2 cm. The scapho-conchal angle is measured between the antihelix and concha and should be close to 90º18.

The main goal of otoplasty in correcting protruding ear is to restore the anatomy and remove the stigma of patients with this deformity. The surgical techniques seek a natural result, symmetry, minimal complications, low recurrence, and rapid recovery.

The smaller detachment and resection of skin in the posterior auricular region, in addition to the absence of fixation points to the mastoid, are important factors for the low rate of complications such as hematomas in the postoperative period, decreasing pain, and achieving postoperative comfort. It is worth highlighting that unlike Eliott, who performed an anterior incision at the edge of the concha, the weakening of the antihelix cartilage was achieved with the use of at least three partial incisions in the anterior region, after which the incised cartilage edges were sutured, and the excess skin in this region was not resected.

The immediate complications that may occur in the first postoperative week are: hematoma, infection, pain, and local discomfort. The most common complication is hematoma, which requires immediate drainage. Unlike our study, the report by Aki et al.19 identified a higher incidence of infection rates (5.1%), hematomas (4.1%), and skin necroses (2.6%).

Complications after the second postoperative week may be caused by local trauma.

Inadequate protruding ear correction, with contour distortion and/or hypercorrection, are more common unwanted results of otoplasty and were observed at an incidence of 11%, similar to the results reported by Aki et al.19.

Combined otoplasty is a simple approach for the correction of protruding ears and displays a high percentage of satisfaction with a low complication rate.This procedure does not require extensive posterior detachment and avoids injury to the neurovascular system of the ear.

The study by Goulart et al.17, unlike ours, reported posterior detachment of the ear in the subperichondrial plane, until good exposure of the auricular cartilage and detachment of the mastoid region was achieved. Goulart et al.17 performed the posterior auricular muscle-associated cartilage incision at four points, defining the antihelix with 2-4 Mustardé sutures.

The combination of techniques is an interesting approach to that can be used in any type of surgery, especially in procedures for correcting larger anatomical details, such as those of the ear. We believe that different ear deformities must be corrected with various techniques, thus leading to greater naturalness and harmony18.

Goulart et al.17 concluded in their study that the best treatment for protruding ears is obtained with the association of several techniques. This combined approach presented natural results and low rates of complication, and both the surgical team and patients were satisfied.

CONCLUSION

The procedure presented in this study was effective.

Resection of a small band (half-moon) in the anterior portion of the concha favors the natural curvature of the antihelix.

The surgical procedure is simple, easily reproducible, provides good results, is associated with a high degree of patient satisfaction, and has a low rate of complications/morbidities.

COLLABORATIONS

|

ORS |

Analysis and/or interpretation of data; statistical analyses; final approval of the manuscript; conception and design of the study; completion of surgeries and/or experiments; writing the manuscript or critical review of its contents. |

|

ORSF |

Analysis and/or interpretation of data; statistical analyses; final approval of the manuscript; conception and design of the study; completion of surgeries and/or experiments; writing the manuscript or critical review of its contents. |

|

CBS |

Analysis and/or interpretation of data; statistical analyses; final approval of the manuscript; conception and design of the study; completion of surgeries and/or experiments; writing the manuscript or critical review of its contents. |

|

PRS |

Analysis and/or interpretation of data; statistical analyses; final approval of the manuscript; conception and design of the study; completion of surgeries and/or experiments; writing the manuscript or critical review of its contents. |

|

SAAP |

Analysis and/or interpretation of data; statistical analyses; final approval of the manuscript; conception and design of the study; completion of surgeries and/or experiments; writing the manuscript or critical review of its contents. |

|

BFSF |

Analysis and/or interpretation of data; statistical analyses; final approval of the manuscript; conception and design of the study; completion of surgeries and/or experiments; writing the manuscript or critical review of its contents. |

|

FF |

Analysis and/or interpretation of data; statistical analyses; final approval of the manuscript; conception and design of the study; completion of surgeries and/or experiments; writing the manuscript or critical review of its contents. |

|

NGN |

Analysis and/or interpretation of data; statistical analyses; final approval of the manuscript; conception and design of the study; completion of surgeries and/or experiments; writing the manuscript or critical review of its contents. |

|

FFGO |

Analysis and/or interpretation of data. |

REFERENCES

1. Tanzer RC, Congenital deformities of the auricle. In: Converse JM, ed. Reconstr Plast Surg. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1977. 1719 p.

2. Yegueros P, Friedland JA. Otoplasty: the Experience of 100 consecutive patients. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;108(4):1045-51. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00006534-200109150-00039

3. Morestin MH. De la reposition et du plissement cosmetiques du pavillon de l'oreille. Rev Orthop. 1903;4:289-303.

4. Luckett WH. A new operation for prominent ears base don the anatomy of the deformity. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1910;10:635.

5. Becker OJ. Correction of protruding deformed ear. Br J Plast Surg. 1952;5(3):187-96. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0007-1226(52)80019-0

6. Converse JM, Nigro A, Wilson FA, Johnson N. A technique for surgical correction of lop ears. Plast Reconstr Surg (1946). 1955;15(5):411-8. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00006534-195505000-00004

7. Converse JM, Wood-Smith D. Technical details in the surgical correction of the lop ear deformity. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1963;31:118-28. PMID: 14022738 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00006534-196302000-00002

8. Gibson T, Davis WB. The distortion of autogenous cartilage grafts: its cause and prevention. Br J Plast Surg. 1958;10:257-74. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0007-1226(57)80042-3

9. Stenström SJ. A "natural" technique for correction of congenitally prominent ears. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1963;32:509-18. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00006534-196311000-00003

10. Sevin K, Sevin A. Otoplasty with Mustarde suture, cartilage rasping, and scratching. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2006;30(4):437-41. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00266-006-0061-4

11. Mustardé JC. The correction of prominent ears using simple mattress sutures. Br J Plast Surg. 1963;16:170-8. PMID: 13936895 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0007-1226(63)80100-9

12. Kayne BL. A Simplified method for correcting the prominent ear. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1967;40(1):44-8. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00006534-196707000-00006

13. Furnas DW. Correction of prominent ears by conchamastoid sutures. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1968;42(3):189-93. PMID: 4878456

14. Spira M, McCrea R, Gerow FJ, Hardy SB. Correction of the principal deformities causing protruding ears. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1969;44(2):150-4. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00006534-196944020-00007

15. Elliott RA Jr. Othoplasty: a combined approach. Clin Plast Surg. 1990;17(2):373-81. PMID: 2189651

16. Hell B, Garbea D, Heissler E, Klein M, Gath H, Langforg A. Otoplasty: a combined approach to different structures of auricle. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1997;26(6):408-13. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0901-5027(97)80003-3

17. Goulart FO, Arruda DSV, Karner BM, Gomes PL, Carreirão S. Correção da orelha de abano pela técnica de incisão cartilaginosa, definição da antélice com pontos de Mustardé e fixação da cartilagem conchal na mastoide. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2011;26(4):602-7.

18. Souza AM, Jorge RC. Cirurgia estética da orelha. In: Cardim VL, Marques A, Morais- Besteiro J, eds. Sociedade Brasileira de Cirurgia Plástica, Estética e Reconstrutiva Regional São Paulo. São Paulo: Atheneu; 1995. p. 145-50.

19. Aki F, Sakae E, Cruz DP, Kamakura L, Ferreira MC. Complicações em Otoplastia: Revisão de 508 Casos. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2006;21(3):140-4.

1. Clinica Saldanha, Santos, SP,

Brazil.

2. Hospital São Lucas, Serviço de Cirurgia

Plástica Osvaldo Saldanha, Santos, SP, Brazil.

3. Universidade Santa Cecília, Serviço de Cirurgia

Plástica Dr. Ewaldo Bolívar de Souza Pinto, Santos, SP, Brazil.

Corresponding author: Osvaldo Ribeiro

Saldanha

Avenida Washington Luis, 142

Santos, SP, Brazil Zip Code

11050-200

E-mail: clinicasaldanha@hotmail.com

Article received: October 21, 2015.

Article accepted: May 17, 2018.

Conflicts of interest: none.

Read in Portuguese

Read in Portuguese

Read in English

Read in English

PDF PT

PDF PT

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to Cite

How to Cite

Mendeley

Mendeley

Pocket

Pocket

Twitter

Twitter