Original Article - Year 2018 - Volume 33 -

Nasolabial interpolation flap for nasal alar reconstruction after skin tumor resection

Retalho nasogeniano de interpolação na reconstrução da asa nasal após ressecção de tumores cutâneos

ABSTRACT

Introduction: The nose is a common site for skin neoplasms. Due to its functional and

esthetic importance, nasal reconstruction, mainly that of the nose ala, is

challenging. The objective is to describe the nasolabial interpolation flap

for nasal alar reconstruction after skin tumor resection.

Methods: Patients with nonmelanoma skin tumors on the nasal ala without involvement of

the alar and supra-alar sulcus underwent reconstruction with a nasolabial

interpolation flap associated with conchal cartilage grafting. Details of

the surgical planning and operative sequence and an analysis of the results

are presented.

Resultados: In the treatment of skin tumors on the nasal ala, results from the

oncological and esthetic point of view should be sought, i.e., maintenance

of the three-dimensional structure and cutaneous features should be

intended.

Conclusion: Use of the nasolabial interpolation flap was effective for nasal alar

reconstruction despite the need for two surgeries.

Keywords: Nose; Reconstructive surgical procedures; Surgical flaps; Skin neoplasms

RESUMO

Introdução: O nariz é sede frequente de neoplasias cutâneas. Pela importância

estético-funcional, a reconstrução do nariz, em especial da asa nasal, é um

desafio. O objetivo é descrever o retalho nasogeniano de interpolação na

reconstrução da asa nasal após ressecção de tumores cutâneos.

Métodos: Pacientes com tumores de pele não melanoma de asa nasal, sem comprometimento

dos sulcos alar ou supra-alar, foram submetidos à reconstrução com retalho

nasogeniano de interpolação associado a enxerto de cartilagem conchal.

Detalhes do planejamento cirúrgico e da sequência operatória, assim como a

análise dos resultados, são demonstrados.

Resultados: No tratamento de tumores de pele localizados na asa nasal, deve-se buscar

resultados sob o ponto de vista oncológico e estético. Assim, a preservação

da estrutura tridimensional e das características cutâneas da asa nasal deve

ser objetivada.

Conclusão: O retalho nasogeniano de interpolação mostrou-se eficaz na reconstrução da

asa nasal, apesar da necessidade de dois tempos cirúrgicos.

Palavras-chave: Nariz; Procedimentos cirúrgicos reconstrutivos; Retalhos cirúrgicos; Neoplasias cutâneas

INTRODUCTION

The importance of aesthetic and functional reconstructions of the nose has been of priority since the first records dated 3000 BC in the Edwin Smith Surgical Papyrus of ancient Egypt1. In 600 BC, Sushruta described nasal reconstruction using mid-frontal and genian flaps in the book Aruyeda2,3. In the 19th century, Johann Friedrich Dieffenbach popularized the use of synthetic nasogenian flaps4. In 1975, Herbert found that the nasogenian skin region is ideal in color and texture for nasal reconstruction5.

Some aspects of nasal reconstruction are established in the literature as proposed by Burget and Menick6. Thus, nasal reconstructions should respect the aesthetic nasal subunits, including the dorsum, tip, columella, wings, sides, and soft triangles. The authors suggested that all subunits must be reconstructed when more than 50% of the subunits are affected and that the incisions should be made such that the scars are camouflaged within them.

Two other important aspects are also recommended: replacement skin should be similar to the original skin thickness, size, color, and texture and restoration of its intricate tridimensional structure7,8. Ideally, surgery restores the aesthetic appearance, so nasal imperfections are not noticed at a normal conversational distance.

A large variety of local flaps have been described in the literature. When selecting a local flap for reconstructing partial defects of the nose, the surgeon is guided by the patient’s characteristics, technical conditions, places offered in each circumstance, and experience itself, considering that creating a flap requires knowledge of the anatomy and tissue movement9.

Skin cancer commonly occurs on the face, especially in the nasal region10. Clearly, treatment involves repairing issues and restoring aesthetic appearance, with the objective of achieving a cure and minimizing deformities.

The incidence of non-melanoma skin cancer on the head and neck is 75%, but 30-35% of such cases occur on the nose. The distribution of these tumors on the nose follows a homogeneous standard; in most studies, the nasal alar subunit is most often affected (21-30%), followed by the dorsum and tip11.

Reconstructing the wing is a challenge, especially with the goal of maintaining the alar sulcus, supra-alar fold, and symmetry of the nostrils and nostril rim with minimal scarring.

OBJECTIVE

The objective of this study was to describe the use of nasolabial interpolation flap in the reconstruction of nasal alar defects that result from skin tumor resection.

METHODS

Valuation

The success of excision of skin cancer and reconstruction of the nasal alar began with careful evaluation of the injury and definition of its margins. We marked the area to be resected and planned the defect reconstruction. For cutaneous defects of the nasal alar, it is generally necessary to support the structural cartilage to prevent nostril stenosis or external nasal valve insufficiency.

Indication

The nasolabial interpolation flap is indicated for defects of the nasal alar in which there is no indication for primer synthesis, a V-Y advancement flap cannot be used in the wing, and there is no involvement of the alar or supra-alar sulcus. The nasogenian skin region, with its pores and sebaceous glands, appears similar to the distal third of the nose.

Marking

The nasolabial interpolation flap consists of a flap designed on the nasolabial folds with a superior pedicle based on the branches of arteries in the subcutaneous facial, lip, and angular areas.

Thus, the flap is designed with the lower edge of the ipsilateral melolabial groove having a width equal to the vertical length of the wing, with the base level above the alar fold and extending slightly farther than the horizontal length of the wing that allows for uniform closure of the donor site without tension. This flap could be peninsular, based on pedicle skin, or island-shaped, based on the subcutaneous tissue and must maintain a medial 90º pivoting angle.

The length of the cartilage graft shell of the ear was marked slightly larger than the horizontal length of the nasal wing.

Surgery

The tumors were resected with a safety margin and free margins were confirmed after evaluating using the congelation method. We then created the flap and kept the distal portion thin and dissected until the plan of major zygomatic muscle at the proximal portion. With posterior access, the conchal cartilage was collected and kept crescent-shaped with concave-convex surfaces.

We continued placing the cartilage graft over the defect with the ends inserted under the skin of the nasal tip and alar sulcus and affixed it to the skin underlying the alar cartilage using absorbable sutures.

We rotated the flap toward the midline, sutured the medial edge to the supra-alar sulcus, and affixed the lateral edge at the lower limit of the defect. Most often, we ignored the distal portion of the flap. The pedicle of the flap interpolation crossed above and saved the alar sulcus. The exposed pedicle was skin and subcutaneous tissue or subcutaneous tissue only.

We then proceeded to synthesizing the primary donor area in two planes with the suture on the nasolabial sulcus and promoting good camouflage of the donor site. We exposed the pedicle with rayon to avoid adhesions and avoid compression.

At 21-28 days, we sectioned the pedicle, removed the redundant tissue (up to 0.5-1 cm in the lateral surface), removed excess fat, and sculpted the subcutaneous tissue. After flap separation, the alar sulcus remains completely natural since no incision or dissection was made in this region.

A third surgery was performed if sufficient aesthetic complaints were received after 2-3 months.

RESULTS

We operated on five patients with non-melanoma tumors in the alar nasal using a nasolabial interpolation flap with an exposed pedicle for reconstruction. Here, we report two cases: one with a cutaneous and subcutaneous pedicle and another with a subcutaneous pedicle only.

Case 1

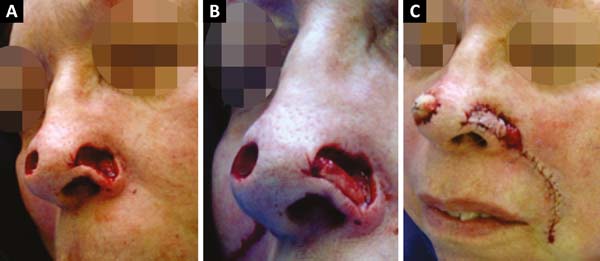

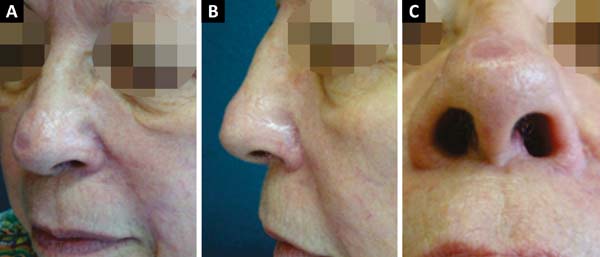

A 66-year-old Caucasian woman with Fitzpatrick skin type II presented with 3 lesions on the nose (right nasal alar, left nasal alar, and tip). We excised the lesions and used a primary suture to affix the right-wing tip graft and nasolabial interpolation flap onto the left wing, taking care to keep the subcutaneous pedicle exposed with the conchal auricular cartilage graft on the right. The histopathology confirmed the diagnosis of micronodular and nodular basal cell carcinoma with clear margins on the right-wing tip. On the left wing, nodular basal cell carcinoma, which was micronodular and sclerodermiform with all margins free of neoplastic involvement, was confirmed (Figures 1, 2 and 3).

Case 2

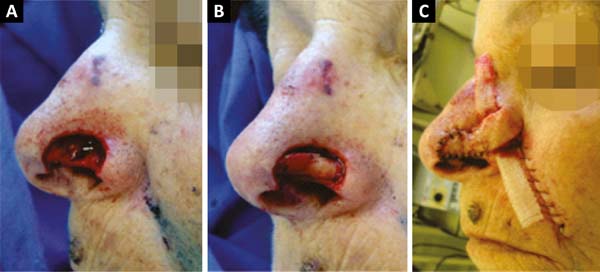

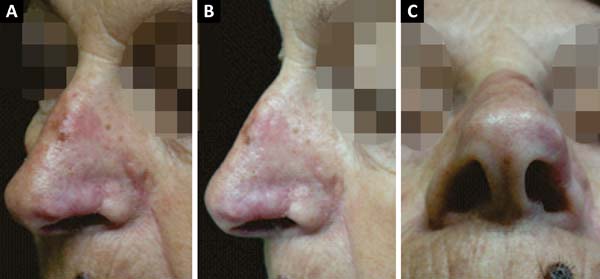

A 70-year-old Caucasian woman with Fitzpatrick skin type III presented with a lesion in the left alar nasal area. We excised the lesion and affixed a nasolabial interpolation flap with the cutaneous and subcutaneous pedicle exposed and associated with the conchal auricular cartilage graft on the left. The histopathology confirmed the diagnosis of nodular and micronodular basal cell carcinoma with margins free of neoplastic involvement (Figures 4, 5 and 6).

DISCUSSION

With increasing life expectancy and an increased incidence of skin cancer, it is important to assess the surgical results from the oncological and aesthetic points of view. Thus, reconstruction of the nasal alar area after the excision of non-melanoma skin cancer tumors constitutes an increasingly common challenge.

According to Burget and Menick, reconstruction of the nasal alar area should respect the limits of the subunit. Thus, surgeons should plan to mask the scars within the limits of the subunit and ensure that the skin covering most closely resembles the original.

The versatility of the nasolabial flap is well recognized in nasal reconstruction used for advancement, transposition, or interpolation. The predominant indication for nasolabial interpolation flap use in reconstruction of the nasal alar is that it deforms the alar sulcus, an important junction between the topographic nose, malar, and upper lip areas. Whenever possible, surgeons should avoid crossing flaps in aesthetically distinct regions, especially when relief is concave margins. Thus, the nasolabial flap transposition violates the alar sulcus, obliterating the valley between the region and alar genian (Figure 7).

The nasal alar is an important aesthetic unit with a free margin and external nasal valve function. To restore function using nasal alar reconstruction, support is needed to enable the cartilage to resist the forces of contraction and promote a stable external valve even in cases without a cartilaginous framework in this subunit. A cartilage graft should be placed near the auricular concha, usually under the flap.

Another advantage of using the nasolabial flap is its good quality because the porous and sebaceous nature of the medial portion of genian region is similar to that of the caudal third of the nose.

A disadvantage of the nasolabial interpolation flap is the need for 2 or 3 surgeries: the first for tumor excision and flap preparation; the second for pedicle sectioning; and a possible third for fine-tuning. Another disadvantage of the nasolabial flap in men is the possible transfer of hair follicles, but they can be removed in the third surgery.

CONCLUSION

The nasolabial interpolation flap is an excellent option in the reconstruction of the nasal alar after cutaneous tumor excision. Despite the need for two surgeries, the final aesthetic result is rewarding and the function is satisfactory.

REFERENCES

1. González-Ulloa M. The Creation of Aesthetic Plastic Surgery. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1985.

2. Whitaker IS, Karoo RO, Spyrou G, Fenton OM. The birth of plastic surgery: the story of nasal reconstruction from the Edwin Smith Papyrus to the twenty-first century. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;120(1):327-36.

3. Destro MWB. Reconstrução do Nariz. In: Mélega JM, ed. Cirurgia Plástica Fundamentos e Arte - Princípios Gerais. Rio de Janeiro: Medsi; 2002. p. 912-29.

4. Dieffenbach JF. Die Nasenbehandlung. In: Dieffenbach JF. Die Operative Chirurgie. Leipzig: F.A. Brockhaus; 1845.

5. Herbert DC, Harrison RG. Nasolabial subcutaneous pedicle flaps. Br J Plast Surg. 1975;28(2):85-9.

6. Burget GC, Menick FJ. Aesthetics, visual perception, and surgical judgment. In: Burget GC, Menick FJ, eds. Aesthetic reconstruction of the nose. St. Louis: Mosby; 1994. p. 1-55.

7. Gokrem S, Tuncali D, Akbuga U, Terzioglu A, Aslan G. Reconstruction of small to medium defects in the soft tissues of the nose with nasalis musculocutaneous V-Y advancement flaps. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg. 2006;40(3):140-7.

8. Rieger RA. A local flap for repair of the nasal tip. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1967;40(2):147-9.

9. Rohrich RJ, Griffin JR, Ansari M, Beran SJ, Potter JK. Nasal reconstruction--beyond aesthetic subunits: a 15-year review of 1334 cases. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;114(6):1405-16.

10. Santos ABO, Loureiro V, Araújo Filho VJF, Ferraz AR. Estudo epidemiológico de 230 casos de carcinoma basocelular agressivos em cabeça e pescoço. Rev Bras Cir Cabeça Pescoço. 2007;36(4):230-3.

11. Netscher DT, Spira M. Basal Cell Carcinoma: An Overview of Tumor Biology and Treatment. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;113(5):74e-94e.

1. Hospital do Servidor Público Estadual de

São Paulo, São Paulo, SP, Brazil.

Corresponding author: Rafael Luis

Sakai

Av. Ibirapuera, 981 - 5º andar - Vila Clementino

São Paulo,

SP, Brazil Zip Code 04029-000

E-mail: rafa_sakai@yahoo.com

Article received: June 01, 2013.

Article accepted: May 17, 2018.

Conflicts of interest: none.

Read in Portuguese

Read in Portuguese

Read in English

Read in English

PDF PT

PDF PT

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to Cite

How to Cite

Mendeley

Mendeley

Pocket

Pocket

Twitter

Twitter