Original Article - Year 2018 - Volume 33 -

Ecchymosis evaluation after internal and external continuous lateral nasal osteotomy in open rhinoplasty

Avaliação da equimose após osteotomia nasal lateral contínua interna e externa na rinoplastia aberta

ABSTRACT

Introduction: The objective is to evaluate the presence of ecchymosis 7 and 15 days after

internal and external lateral nasal osteotomy in open rhinoplasty.

Methods: A prospective evaluation of 15 patients who underwent open rhinoplasty with

lateral nasal osteotomy was conducted. The patients were allocated into two

groups. Those who underwent external lateral nasal osteotomy were included

in group A (n = 6), while those who underwent internal osteotomy were

included in group B (n = 9). The patients were evaluated on postoperative

days 7 and 15, and the presence or absence of ecchymosis was recorded.

Results: In group A, we observed that on postoperative day 7, 3 patients (50%) had

ecchymosis and 3 (50%) showed no changes in skin color. On postoperative day

15, the same group had 2 patients (25%) with ecchymosis and 4 (75%) without

changes. On the other hand, in group B, 3 patients (33.4%) had ecchymosis

and 6 (66.6%) showed no changes on postoperative day 7. In the same group, 1

patient (11.1%) had ecchymosis and 8 (88.9%) showed no changes 15 days after

surgery.

Conclusion: Despite the lower incidence of ecchymosis in internal fractures on

postoperative days 7 and 15, no statistical significance was observed

between the two techniques.

Keywords: Rhinoplasty; Osteotomy; Nose; Ecchymosis

RESUMO

Introdução: O objetivo é avaliar a presença de equimose com 7 e 15 dias após osteotomia

nasal lateral interna e externa na rinoplastia aberta.

Métodos: Análise prospectiva, dos pacientes submetidos à rinoplastia aberta, com

osteotomia nasal lateral com total de 15 pacientes. Os pacientes foram

alocados em dois grupos. Aqueles submetidos à osteotomia nasal lateral

externa formaram o grupo A (n = 6) e os submetidos à osteotomia interna, o

grupo B (n = 9). Foram avaliados com 7 e 15 dias de pós-operatório e

registrada a presença ou ausência de equimose.

Resultados: Dentro do grupo A evidenciamos no 7º dia de pós-operatório 3 (50%) pacientes

com equimose e 3 (50%) sem alteração na tonalidade da pele. Com 15 dias de

pós-operatório, o mesmo grupo apresentava 2 (25%) pacientes com equimose e 4

(75%) sem alteração. Já no grupo B foram identificados no 7º dia após o

procedimento 3 (33,4%) pacientes com presença de equimose e 6 (66,6%) sem

alteração. O mesmo grupo após 15 dias do procedimento apresentou 1 (11,1%)

paciente com equimose e 8 (88,9%) sem alteração.

Conclusão: Apesar da fratura interna apresentar menor incidência de equimose no sétimo e

décimo quinto dias de pós-operatório, não houve relevância estatística na

comparação entre as técnicas.

Palavras-chave: Rinoplastia; Osteotomia; Nariz; Equimose

INTRODUCTION

Lateral nasal osteotomy may be required during various aesthetic and restorative rhinoplasties and can be performed in many ways. Much has been discussed about the most appropriate technique to perform lateral osteotomy. Currently, the most commonly used techniques are internal continuous and external percutaneous osteotomy1. Both techniques involve blind manipulation, which can cause mucosal injury, which is associated with bleeding and local swelling2,3.

Depending on the severity of the edema and ecchymosis, it difficult for the patient and surgeon to perceive the outcome, as the technique may also lead to a prolonged recovery time and interruption of patients’ social life during that period. Patients’ desire for rapid recovery and quick return to normal activities has influenced surgeons to opt for less morbid and minimally invasive techniques4,5. Among the alterations that occurred with surgical trauma, ecchymosis and edema attracted the most patient attention. In this context, assessing which nasal osteotomy presents a lower degree of ecchymosis in the postoperative period aims at guiding the surgeon in choosing the technique with a shorter time to recovery.

OBJECTIVE

To evaluate the presence of ecchymosis after external and internal lateral nasal osteotomy in patients who underwent open rhinoplasty, on postoperative days 7 and 15.

METHODS

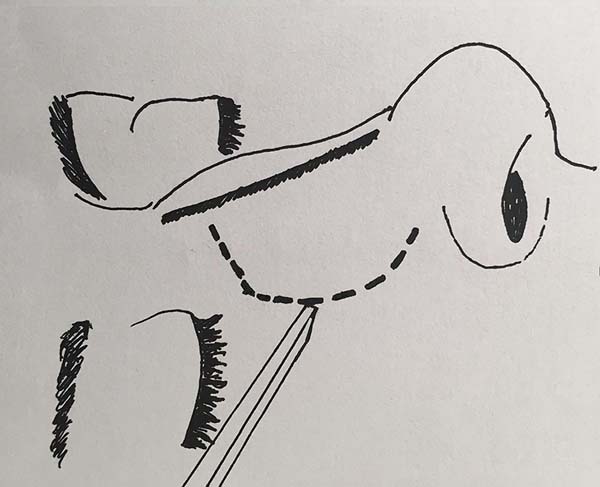

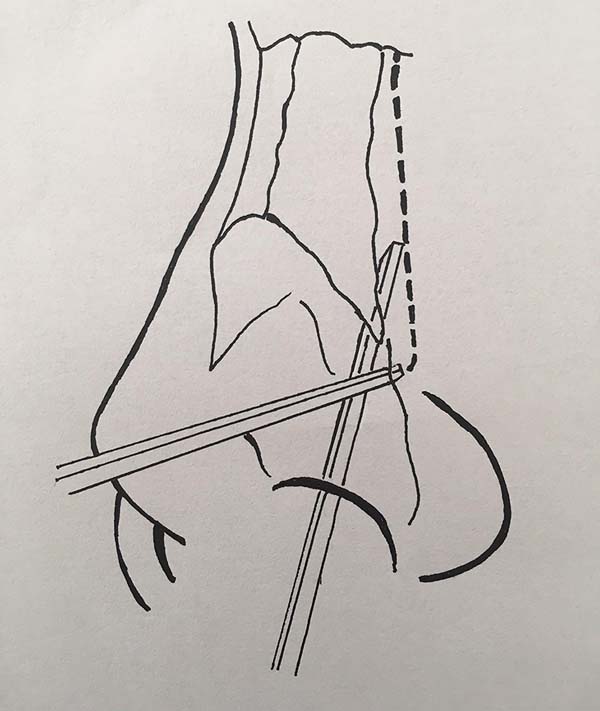

In the period from April to November 2016, a prospective evaluation of patients who underwent open rhinoplasty with continuous lateral nasal fracture was conducted. All the patients underwent operation at the plastic surgery residency service of Barata Ribeiro Municipal Hospital, in Rio de Janeiro, RJ. Those who underwent external and internal lateral continuous nasal osteotomy (Figures 1 and 2, respectively) were included in groups A and B, respectively.

The allocation of each patient was in accordance with the day of the week on which the operation was performed. Those who underwent operation on even days were assigned to group A, while those who underwent operation on odd days were assigned to group B. Patients who had comorbidities or were taking drugs that could interfere with bleeding or coagulation processes were excluded. African patients were also excluded because of the difficulty to analyze for the presence of ecchymosis.

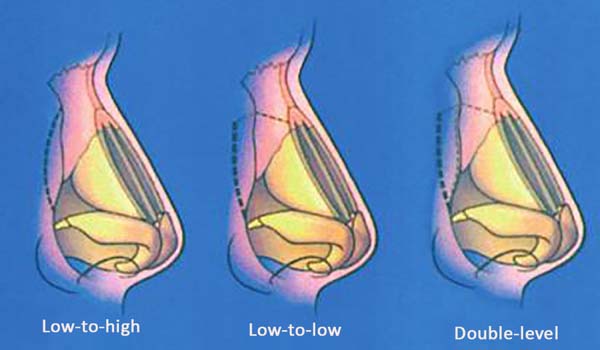

The fracture type was standardized as all “low-to-low,” with paramedian fracture associated with cases that presented to no ceiling opening. The first author, under the guidance of a staff surgeon, performed all the fracture-related procedures, except that which was performed, for some reason, by the supervisor.

The size of osteotomes was standardized; that is, external osteotomies were performed with a 2-mm osteotome, and internal osteotomies were performed with a 4-mm osteotome, with guidance. The fracture line was previously infiltrated with 2 ml of anesthetic solution with 1:80,000 adrenaline (0.9% saline solution - 30 ml + 2% lidocaine - 30 ml + 1% ropivacaine - 20 ml + 1 mg/ml adrenaline - 1 ml) on both sides, followed by periosteal elevation and, finally, osteotomy.

During anesthetic induction, a 4-mg dose of dexamethasone was administered to all the patients for antihematic effects. Postoperative care was also standardized by prescribing high headboard and cold compress on the eyes for 15 minutes every 4 hours under nursing care. The patient was advised not to use any product that would interfere with edema or ecchymosis.

In the postoperative prescriptions, only dipyrone as an analgesic at a dose of 1 g every 4 hours and cefazolin as an antibiotic at 1 g every 8 hours were administered in the first 48 hours. No anti-inflammatory drugs were used in the postoperative prescriptions. A nasal tampon was also placed at the end of surgery, with dressings moist with the same solution as in the previous infiltration and removed after 48 hours. Dressing with Micropore and Aquaplast were then maintained until postoperative day 7.

The patients included in the study were evaluated on postoperative days 7 and 15 during outpatient consultation to define the presence or absence of ecchymosis. The results were then recorded in a protocol datasheet. The presence of ecchymosis was defined when the patients presented changes in skin color according to the Legrand du Saulle ecchymotic spectrum in the periorbital nasal or maxillary region (Figure 3). The absence of ecchymosis was defined when no skin color change was observed in these regions (Figure 4). The presence or absence of ecchymosis was evaluated in all the cases by the main author.

All the patients signed an informed consent form. The obtained data were organized in 2 × 2 contingency tables and analyzed using the Fisher exact test. The method was a nonparametric data approach that was aimed at assessing whether two independent samples are from the same population and especially designed for small samples.

The null hypothesis (H0) indicates no significant difference in ecchymosis occurrence rate according to the adopted surgical procedure. The alternative hypothesis (H1) indicates that the ecchymosis occurrence rate depends on the adopted surgical procedure. The Fisher exact test is based on a hypergeometric distribution. Therefore, the p value depends on the marginal totals in the table and, consequently, on the group sample values. The significance alpha level adopted was 0.05, so p values of <0.05 indicated rejection of H0. The statistical packages used were BioEstat 5.3 and Statistica 8.0 (StatSoft, Inc.2007).

RESULTS

The total number of patients who underwent operation was 21 (n = 21). All underwent open rhinoplasty with low-to-low lateral nasal osteotomy with an associated paramedical fracture. Of these patients, 7 had an external fracture (group A) and 11 had an internal fracture (group B). One patient was excluded from group A because the fracture-related procedure was performed by the supervisor, and 2 Africans were excluded from group B; thus, 6 patients remained in group A, and 9 remained in group B. The ages ranged from 18 to 40 years, with an average of 28 years, in group A and from 16 to 49 years, with an average of 32 years, in group B. In group A, 5 patients (71.4%) were female and 2 (28.6%) were male. In group B, 8 patients (88.9%) were female and 1 (11.1%) was male.

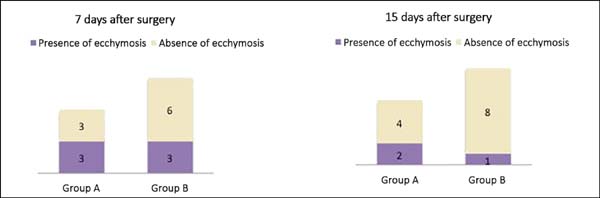

In group A, we observed on postoperative day 7 that 3 patients (50%) had ecchymosis and 3 (50%) showed no changes in skin color. On postoperative day 15, the same group presented 2 patients (25%) with ecchymosis and 4 (75%) without changes. On the other hand, in group B, 3 patients (33.4%) had ecchymosis and 6 (66.6%) showed no changes on postoperative day 7. In the same group, 1 patient (11.1%) had ecchymosis and 8 (88.9%) showed no changes 15 days after surgery (Figure 5).

After assessing the proportions of the results, no significant differences were observed in the occurrence of ecchymosis depending on the fracture-related procedure performed (Tables 1 and 2).

| Group A | Group B | |

|---|---|---|

| With ecchymosis | 50% | 33.3% |

| Without ecchymosis | 50% | 66.7% |

| Group A | Group B | |

|---|---|---|

| With ecchymosis | 33.3% | 11.1% |

| Without ecchymosis | 66.7% | 88.9% |

DISCUSSION

As a main rhinoplasty component, lateral nasal osteotomy is considered the main cause of edema and ecchymosis during the postoperative period6. This, however, aims at closing the open ceiling, narrowing the wide nasal dorsum, or correct irregularities. To achieve one of these goals with osteotomy, the procedure can be performed in 3 ways as follows (Figure 6): low-to-high, low-to-low, and double level, among which the latter is associated with paramedian fractures. In this study, we chose to maintain the most frequently used technique in the service routine, that is, the low-to-low form with associated paramedian fracture, both for internal and external fractures.

The use of narrowing osteotomes in the study was aimed at reducing the swelling and ecchymosis during the postoperative period. This was already demonstrated initially by Thomas and Griner7 in a study with narrowing osteotomes in corpses, which showed the benefit of preserving the nasal support, consequently causing less swelling and ecchymosis. Soon after, Tardy and Denneny8 found similar advantages when using 2- to 3-mm osteotomes. Kuran et al.9 showed a statistically significant difference in intranasal injury in corpses between using 3- and 5-mm-wide osteotomes (33% vs. 94%). Finally, Becker et al.10 also concluded that 2.5- to 3-mm osteotomes produced less intranasal trauma when used for internal lateral nasal fractures.

In 2005, Kara et al.11 demonstrated that subperiosteal tunnel construction in the fracture line significantly decreased the risk of ecchymosis. In 2009, Al-Arfaj et al.12 added significant results to the reduction of ecchymosis after osteotomy with previous periosteal elevation, which justifies the use of this technique in our study.

Moreover, with a subjective analysis of ecchymosis, Giacomarra et al.13 and Hashemi et al.14 support the use of external osteotomy in promoting less swelling and ecchymosis when compared with internal osteotomy. The study by Sinha et al.15 also presented less ecchymosis in external osteotomies; however, their results showed no statistical significance.

Many argue that the advantage of external osteotomy is because of the lower risk of intranasal trauma, which promotes less intraoperative bleeding. By contrast, Yücel16, who also used periosteal elevation prior osteotomy and cold compresses in the postoperative period, as in our study, but with a larger number of cases, showed that internal osteotomy significantly reduced the risk of ecchymosis 48 hours after surgery.

In addition, three other studies identified no significant difference between the techniques, with a tendency of favoring internal osteotomy17-19. Tirelli et al.20 proposed fracture techniques with ultrasonic instruments and obtained satisfactory results. However, the availability of these tools to be used in our current clinical practice is still limited.

In view of the data initially obtained, together with the results of the meta-analysis performed by Ong et al.6, published in 2016, by analyzing the aforementioned works, we can infer that the appropriate osteotomy is the technique performed by a surgeon with precise control. Indeed, it presents outcomes with a low risk of complications, minimizing postoperative sequelae such as bleeding, edema, and ecchymosis.

Although internal fractures had a lower incidence of ecchymosis on postoperative days 7 and 15, when compared among themselves, these techniques did not present a statistically significant difference. Currently, clear recommendations cannot be indicated; thus, other studies are required to confirm the efficacy of one technique over the other.

COLLABORATIONS

|

FPM |

Analysis and/or interpretation of data; statistical analyses; conception and design of the study; completion of surgeries and/ or experiments; writing the manuscript or critical review of its contents. |

|

HB |

Writing the manuscript or critical review of its contents. |

|

JBM |

Writing the manuscript or critical review of its contents. |

|

BPSFF |

Writing the manuscript or critical review of its contents. |

|

FGOQ |

Writing the manuscript or critical review of its contents. |

|

BMBO |

Final approval of the manuscript; conception and design of the study. |

|

CEJB |

Analysis and/or interpretation of data; final approval of the manuscript; conception and design of the study; writing the manuscript or critical review of its contents. |

REFERENCES

1. Rohrich RJ, Ahmad J. Rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;128(2):49e-73e. PMID: 21788798 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0b013e31821e7191

2. Rohrich RJ, Krueger JK, Adams WP Jr, Hollier LH Jr. Achieving consistency in the lateral nasal osteotomy during rhinoplasty: an external perforated technique. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;108(7):2122-30. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00006534-200112000-00051

3. Cochran CS, Roostaeian J. Use of the ultrasonic bone aspirator for lateral osteotomies in rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;132(6):1430-3. PMID: 24281572 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.prs.0000434404.83692.5b

4. Kargi E, Hosnuter M, Babucçu O, Altunkaya H, Altinyazar C. Effect of steroids on edema, ecchymosis, and intraoperative bleeding in rhinoplasty. Ann Plast Surg. 2003;51(6):570-4. PMID: 14646651 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.sap.0000095652.35806.c5

5. Taskin U, Yigit O, Bilici S, Kuvat SV, Sisman AS, Celebi S. Efficacy of the combination of intraoperative cold saline-soaked gauze compression and corticosteroids on rhinoplasty morbidity. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;144(5):698-702. PMID: 21493314 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0194599811400377

6. Ong AA, Farhood Z, Kyle AR, Patel KG. Interventions to Decrease Postoperative Edema and Ecchymosis after Rhinoplasty: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016;137(5):1448-62. PMID: 27119920 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0000000000002101

7. Thomas JR, Griner N. The relationship of lateral osteotomies in rhinoplasty to the lacrimal drainage system. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1986;94(3):362-7. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/019459988609400319

8. Tardy MA Jr, Denneny JC. Micro-osteotomies in rhinoplasty. Facial Plastic Surg. 1984;3:137-45.

9. Kuran I, Ozcan H, Usta A, Bas L. Comparison of four different types of osteotomes for lateral osteotomy: a cadaver study. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 1996;20(4):323-6. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF00228464

10. Becker DG, McLaughlin RB Jr, Loevner LA, Mang A. The lateral osteotomy in rhinoplasty: clinical and radiographic rationale for osteotome selection. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;105(5):1806-16. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00006534-200004050-00031

11. Kara CO, Kara IG, Topuz B. Does creating a subperiosteal tunnel influence the periorbital edema and ecchymosis in rhinoplasty? J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005;63(8):1088-90. PMID: 16094573

12. Al-Arfaj A, Al-Qattan M, Al-Harethy S, Al-Zahrani K. Effect of periosteum elevation on periorbital ecchymosis in rhinoplasty. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2009;62(11):e538-9. PMID: 18838319 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bjps.2008.05.047

13. Giacomarra V, Russolo M, Arnez ZM, Tirelli G. External osteotomy in rhinoplasty. Laryngoscope. 2001;111(3):433-8. PMID: 11224772 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00005537-200103000-00011

14. Hashemi M, Mokhtarinejad F, Omrani M. A Comparison between External versus Internal Lateral Osteotomy in Rhinoplasty. J Res Med Sci. 2005;10(1):10-5.

15. Sinha V, Gupta D, More Y, Prajapati B, Kedia BK, Singh SN. External vs. internal osteotomy in rhinoplasty. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;59(1):9-12. PMID: 23120374 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12070-007-0002-9

16. Yücel OT. Which type of osteotomy for edema and ecchymosis: external or internal? Ann Plast Surg. 2005;55(6):587-90. PMID: 16327456

17. van Loon B, van Heerbeek N, Maal TJ, Borstlap WA, Ingels KJ, Schols JG, et al. Postoperative volume increase of facial soft tissue after percutaneous versus endonasal osteotomy technique in rhinoplasty using 3D stereophotogrammetry. Rhinology. 2011;49(1):121-6.

18. Gryskiewicz JM, Gryskiewicz KM. Nasal osteotomies: a clinical comparison of the perforating methods versus the continuous technique. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;113(5):1445-56. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.PRS.0000113031.67600.B9

19. Kiliç C, Tuncel Ü, Cömert E, Sencan Z. Effect of the Rhinoplasty Technique and Lateral Osteotomy on Periorbital Edema and Ecchymosis. J Craniofac Surg. 2015;26(5):e430-3.

20. Tirelli G, Tofanelli M, Bullo F, Bianchi M, Robiony M. External osteotomy in rhinoplasty: Piezosurgery vs osteotome. Am J Otolaryngol. 2015;36(5):666-71. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amjoto.2015.05.006

1. Hospital Municipal Barata Ribeiro, Rio de

Janeiro, RJ, Brazil.

2. Sociedade Brasileira de Cirurgia Plástica, São

Paulo, SP, Brazil.

3. Sociedade Brasileira de Queimaduras, Rio de

Janeiro, RJ, Brazil.

4. International Society of Aesthetic Plastic

Surgery, Hanover, NH, USA.

5. Hospital Municipal Pedro II, Rio de Janeiro,

RJ, Brazil.

Corresponding author: Henrique

Biavatti

Rua Visconde de Niterói, 1450

Mangueira, RJ, Brazil Zip

Code 20550-200

E-mail: hikebiavatti@gmail.com

Article received: February 05, 2017.

Article accepted: May 17, 2018.

Conflicts of interest: none.

Read in Portuguese

Read in Portuguese

Read in English

Read in English

PDF PT

PDF PT

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to Cite

How to Cite

Mendeley

Mendeley

Pocket

Pocket

Twitter

Twitter