Original Article - Year 2018 - Volume 33 - Issue 2

Correction of palatine fistulas with a musculo-mucosal buccinator flap: results of 6 cases after 27 years

Correção de fissura palatina com retalho musculo-mucoso de bucinador: resultados de 6 casos após 27 anos

ABSTRACT

Introduction: The buccal musculo-mucosal patch, described in 1989, can be used to correct

palatine fistulas and fissures with stretching of the soft palate, or to

cover bloody areas after tumor resection.

Methods: This is an analysis of the 27-year postoperative results for 6 patients who

underwent operation at Base Hospital and Santa Casa de São José do Rio Preto

between 1984 and 1989, and reassessed in 2016, when a myo-buccinator mucosa

was used for cleft palate correction.

Results: Of the 36 operated cases, 6 were reevaluated after 27 years, of which 5 had

primary correction and 1 had a secondary correction (fistula after cleft

palate closure). All the cases had satisfactory results in terms of

maxillary growth, correction of the palatine fistula, and speech

function.

Conclusion: Although not statistically significant, the present study demonstrated that

the buccal musculo-mucosal flap is an adequate procedure for correction and

stretching of the palate, with normal or near-normal maxillary growth and

practically normal speech even without adequate phono-audiological

treatment.

Keywords: Cleft palate; Cleft lip; Velopharyngeal insufficiency; Surgical flap; Fistula

RESUMO

Introdução: O retalho miomucoso de músculo bucinador, descrito em 1989, pode ser

utilizado para corrigir fístulas palatinas, fissuras com alongamento do

palato mole ou cobrir áreas cruentas após ressecções de tumores.

Métodos: Trata-se da análise do resultado após 27 anos de 6 casos de pacientes

operados no Hospital de Base e na Santa Casa de São José do Rio Preto, no

período de 1984 a 1989, e reavaliados em 2016, nos quais foram realizados

retalhos miomucosos de bucinador para correção de fissura palatina.

Resultados: Dos 36 casos operados, 6 foram reavaliados após 27 anos, dos quais 5

trataram-se de correção primária e 1 de correção secundária (fístula após

fechamento de fissura palatina). Todos os casos obtiveram resultados

satisfatórios no crescimento maxilar, na correção da fistula palatina e na

função da fala.

Conclusão: Apesar de estatisticamente não significativo, o presente estudo demonstrou

que o retalho miomucoso de músculo bucinador para correção e alongamento do

palato é um procedimento adequado, com resultados de crescimento maxilar

normal ou próximo disso e fala praticamente normal, mesmo sem adequado

tratamento fonoaudiológico.

Palavras-chave: Fissura palatina; Fenda labial; Insuficiência velofaríngea; Retalhos cirúrgicos; Fístula

INTRODUCTION

In 1989, the author described1 his experience with the use of the musculo-mucosal buccinator2 flap to correct palatine fistulas and fissures with soft palate elongation when the fissured slopes are short or in cases of fissure correction that resulted in primary treatment of the short palate with its phonological consequences. It also covers areas of bloody post-resection site of tumors within its rotation arc and treatment of mandibular osteomyelitis1.

The anatomy is described again according to the initial studies and the technique for obtaining the flap. Six cases of palatine fissures treated with palatoplasty with a follow-up period of 27 years were found in the original publication series and were included in this study.

OBJECTIVE

This study aimed to review the statements and observations mentioned initially (1989) regarding the use of the musculo-mucosal buccinator flap. In addition, it compared a case treated with the classic techniques that also had a 27-year postoperative follow-up and had a similar treatment solution and evolution.

METHODS

The results after 27 years of follow-up of 6 patients treated with a mucosal buccinator for cleft palate correction at Base Hospital and Santa Casa de São José do Rio Preto from 1984 to 1989 were analyzed and reassessed in 2016. The present study follows the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and obtained signed Informed Surgical Consent forms from the patients included in the study.

Anatomy

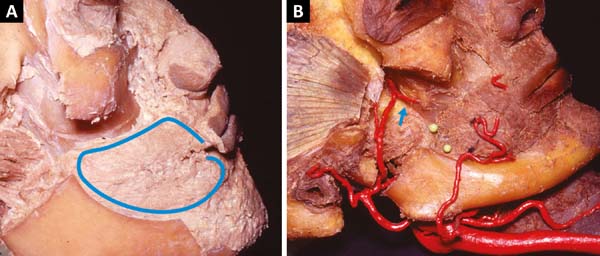

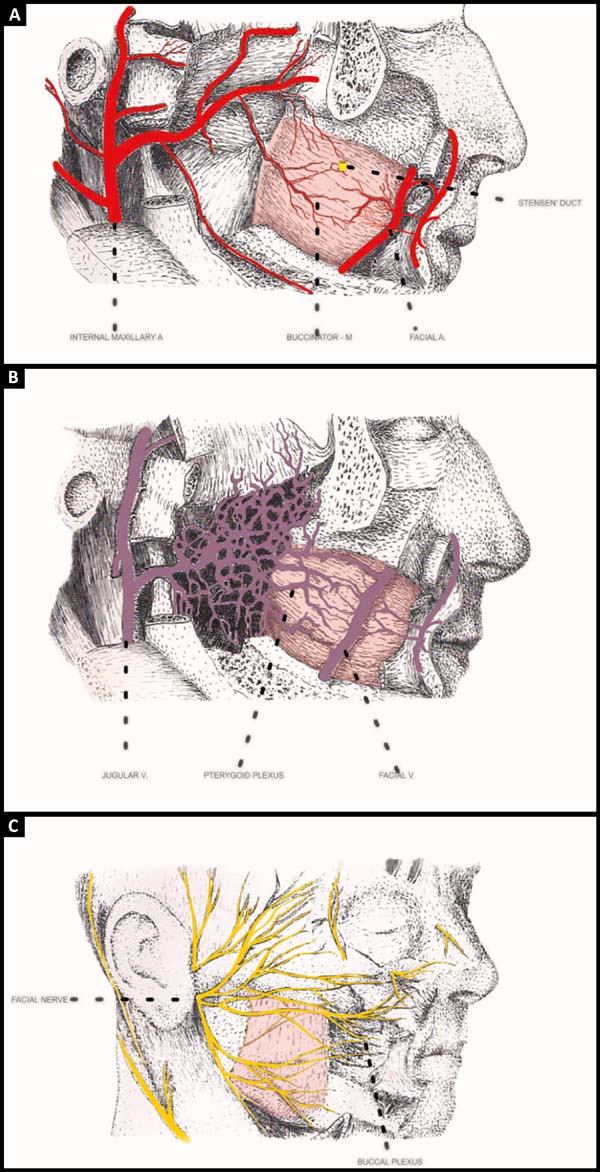

The buccinator muscle is located deep in the cheek and has a slightly quadrangular shape (Figure 1A). Its inner surface is covered by the oral mucosa. The other surface is in contact with the masseter muscle, mandible branch, medial pterygoid muscle, buccopharyngeal fascia, and adipose body of the cheek (Bichat’s adipose ball). Between it and the oropharyngeal fascia is a loose areolar plane that facilitates dissection-divulsion and obtaining of the flap.

Previously, its fibers intersect with those of the orbicularis muscle and later are inserted in the mandibular raphe, superiorly in the maxilla and inferiorly in the branch of the mandible (Figure 1B). It is transposed by the parotid duct at the height of the second upper molar tooth, slightly above the center of the muscle3,4.

Arterial irrigation is done through 3 main origins, the buccal artery, and the branch of the internal jaw that irrigates the posterior half of the muscle, horizontally from front to back. The anterior portion receives branches of the facial artery 1 cm lateral to the corner of the mouth, giving off horizontal branches to the muscle5-9. The third branch is the posterosuperior alveolar6 branch of the internal maxillary artery that irrigates the muscle in its superior posterior portion.

There are consistent anastomoses between all these arteries, which can be found on the lateral surface3,10 of the muscle or within its fibers. This network also has anastomoses with branches of the infraorbital artery (Figure 2A)3,10,11.

Venous drainage is rich with some of the arteries that drain into the pterygoid plexus and then into the internal maxillary vein. Another previous collector is the facial vein. A venous plexus also surrounds the parotid duct (Figure 2B)4.

The motor innervation of the buccinator muscle passes through the facial nerve that emerges near the adipose body of the cheek12,13 from posterior to anterior in the oral plexus (Figure 2C)14,15. This set gives the possibility of obtaining part of the muscle without undermining the remaining portion. Sensory innervation of the buccal mucosa that is adhered to the buccinator muscle is made by branches of the maxillary nerve.

The buccinator muscle is part of a sphincteric muscular system that includes the upper constricting muscle of the pharynx and orbicularis muscle, which facilitates suctioning, whistling, and propulsion of food during chewing. It also has an influence on the toning of the lips and symmetry of the labial commissures16.

Obtaining retail

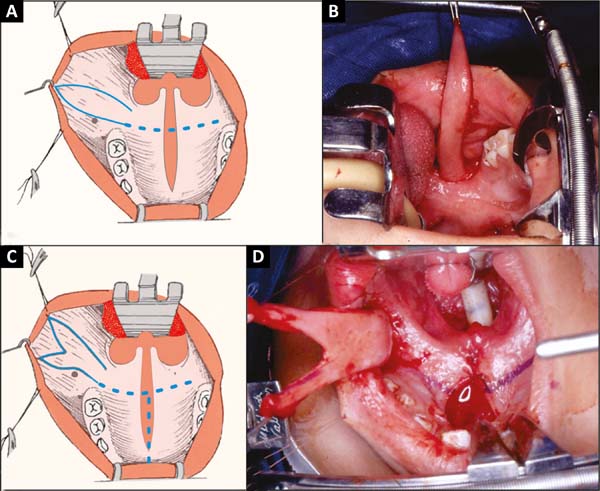

Under general anesthesia, the patient underwent orotracheal intubation fixed at the median line, in the horizontal dorsal decubitus and Trendelenburg positions, hyperextended head, the surgeon sitting at her head, and mouth opened with a static mouth retractor (Rose position). The spindle was obtained at a maximum of 1.5 cm in width in infancy and 2 cm in adulthood, from the labial commissure to the mandibular raphe, ending there with the same width of the center of the flap, and just below the osteo (Figure 3A and B).

If the extremity is in Y, the anterior portions advance slightly in the upper and lower labial mucosa (Figure 3C and 3D). The flap is started from the angle of the mouth. The scaly mucosa is incised only at the end. Scissors are then attached, and the muscle attached to the mucosa is removed using the scissors on the demarcated line, centimeter by centimeter to the mandibular ramus. Release of the oropharyngeal fascia muscle is easy1,2.

In this procedure, pterygoid plexus veins must be ligated and sectioned. The adipose body of the cheek will always be exposed and should be compressed with gauze soaked in adrenaline solution at a concentration of 1:200,000 by using a retractor. When the flap is in Y, the orbicular artery of the lips is found early in the divulsion and can be ligated and sectioned. The posterior vascular pedicle enters the flap in front of raphe in which the muscle and mucosa remain fixed.

The donor area is closed with absorbable wires with some separate stitches and then anchored using continuous stitches. To facilitate this procedure, the opening of the static retractor is reduced. The greasy body of the face remains in its place of origin.

The point of rotation of the flap obtained is in the raphe, and the arch is made behind the tuberosity of the maxilla, with the end of the flap reaching to the anterior region of the hard palate. The flap is extensible, reaching areas more distant than its original measurement before being obtained (Figure 3B and 3D).

Palatal stretching

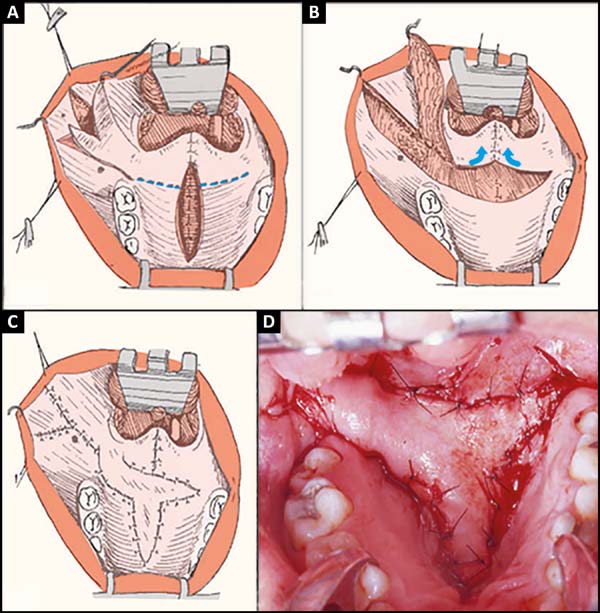

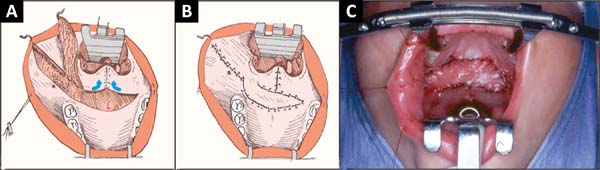

After obtaining the fusiform flap, a transverse incision is made between the hard and soft palates, releasing the mucosa and musculature between them until reaching the pedicle base of the raised flap. On the nasal side, the mucosa is partially detached from the hard palate. The loose musculature is drawn back toward the posterior pharynx and sutured in the midline point to point (non-absorbable) until it reaches maximum tension transversely (muscular V-Y)1,2. In this way the tendency of the soft palate, besides lengthening, turns backward. The buccinator flap is then rotated 180º along its axis and sutured over the blown area (Figure 4A-B-C).

Correction of palatine fistulas

In fistulas of the junction between the hard and soft palates, which are the most common, the procedure is similar to that for cases of stretching. If necessary, a mucosal flap in the “book sheet” of the palate is used to cover the nasal lining. Stretching is always obtained as a consequence of fistula closure1,2.

The same occurs with previous fistulas. Retractions of the fistula border make the lining, and the flap in this case in Y closes the fistula and lengthens the palate (Figure 5A-B-C).

Closure of the primary palature with stretching

When the soft palate slopes are narrow, closure using the classical techniques17-19 may result in a short palate, causing future difficulties in phonation. Under these conditions, it is desirable to lengthen the palate primarily.

The free edges of the cleft are detached, the nasal mucosa is approached throughout its length, the hard and soft palate are separated by transverse incision, and the muscles are sutured in V-Y. A Y-flap is obtained and rotated 180º on the pedicle. One of the legs covers the hard longitudinal area of the hard palate and the other suture transversely over the blistering area between the two palates (Figure 5A-B-C-D)1,2.

RESULTS

Results after 27 years

After 27 years of the initial publication, the author was able to contact only 6 of the 36 patients with cleft palate treated using a buccinator muscle flap1. Five had primary corrections, with the use of a fusiform flap at the beginning of the experiment in one and a Y flap in four. One of them had a secondary correction, and one did not have preoperative photographs.

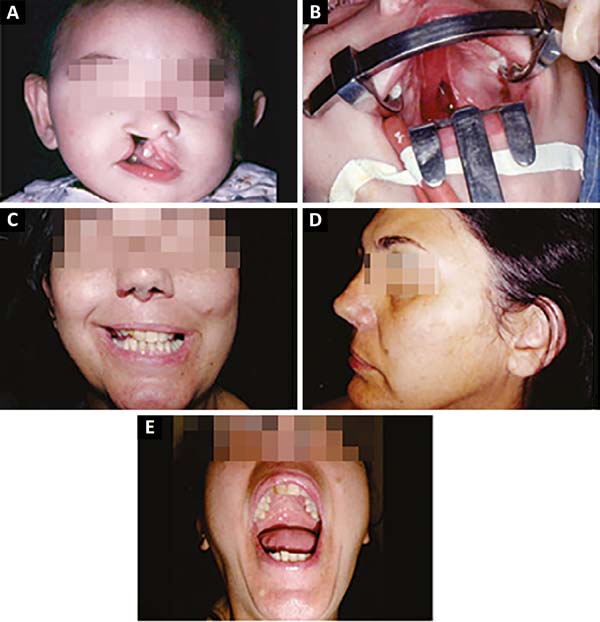

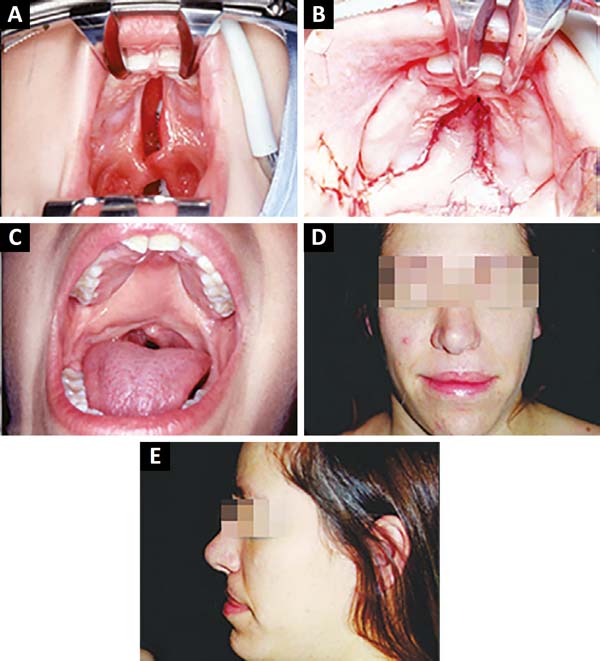

The patient in figure 6A-B-C-D-E, a receptionist, underwent palate correction with fusiform flap stretching and closure of the soft and hard palates with the classic technique using palatal flaps. He did not undergo any orthodontic or phoniatric treatment, despite the mild speech difficulty and hypoplastic jaw, with collapse to the right already visible in the preoperative period in childhood.

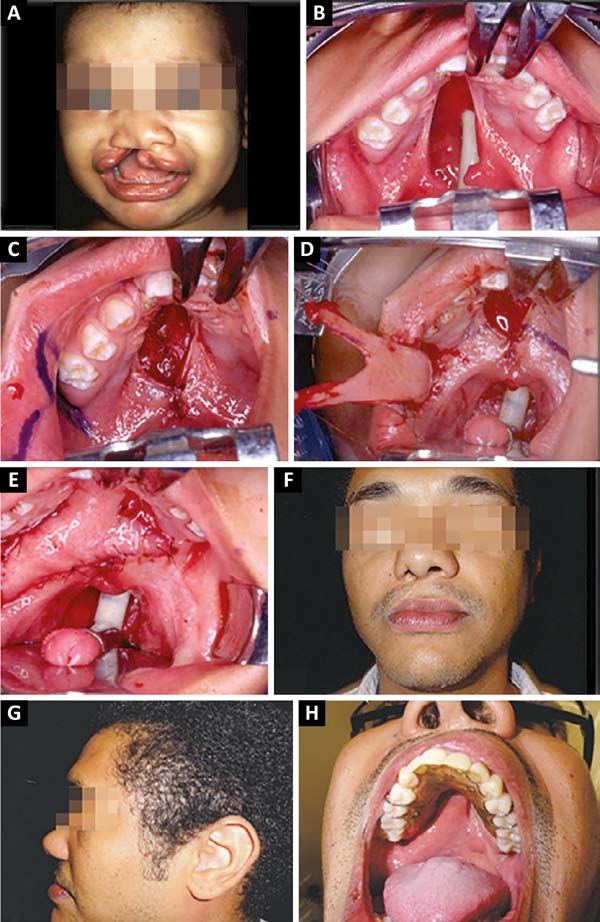

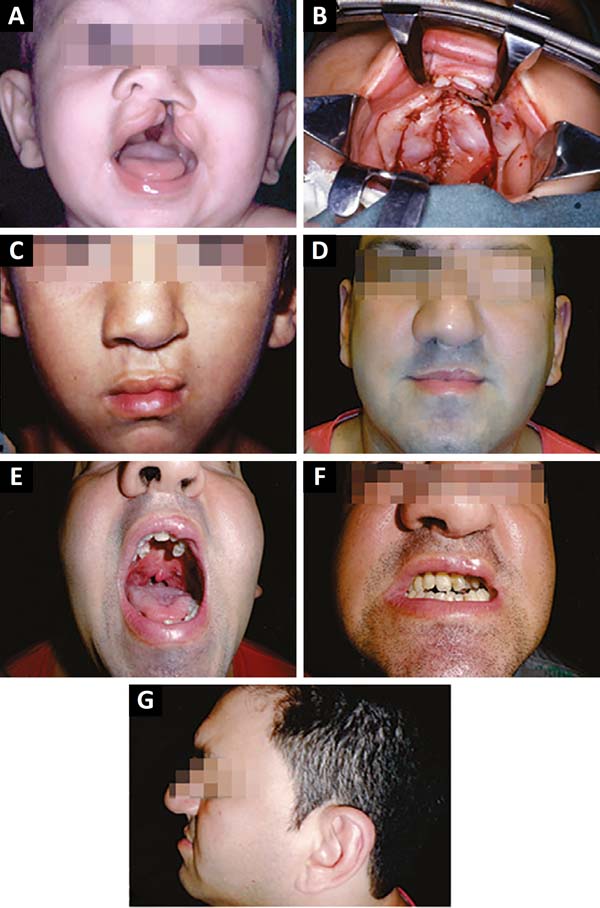

The patient in figure 7A-B-C-D-E-F-G-H, an economist, underwent initial correction of the lip with healplasty at 4 months old20, correction of the palate with a buccinator flap in Y at 1.5 years old, and rhinoplasty at 16 years old. He attained a normal bite with orthodontics and partial dentures. He did not undergo phonological treatment, had normal voice, and slight inversion of the lip projection (Figure 7G).

The patient in figure 8 A-B-C-D-E-F-G-H, an accountant, did not undergo orthopedic treatment of the jaw or orthodontics. He lost some teeth due to bad conservation that were replaced, speech and bite normal. In the distension of the facial region of the buccinator, he could not project to the right (Figure 8F), but he did not mention any functional disturbance for this reason.

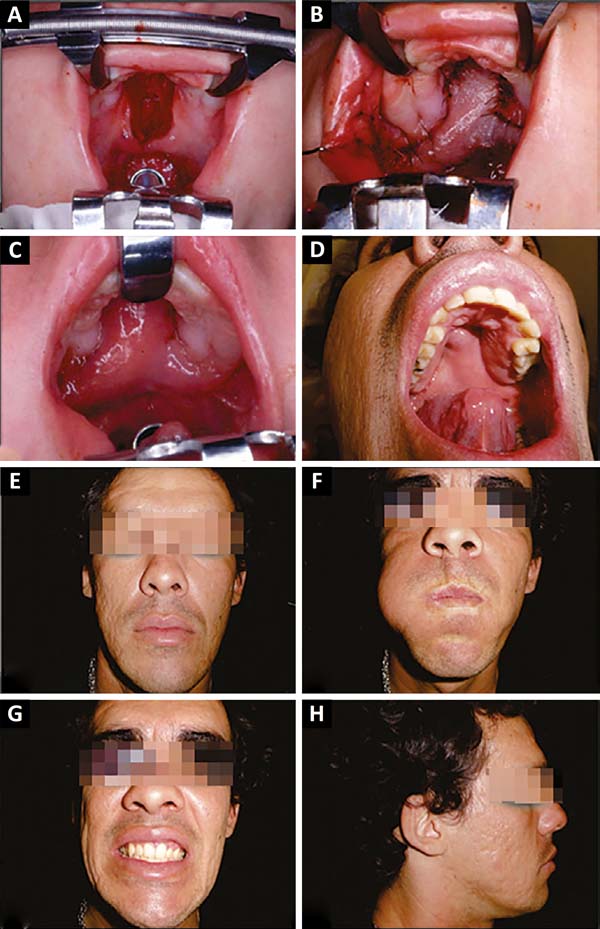

The patient in figure 9 A-B-C-D-E, a plastic surgeon, underwent lip surgery at 4 months (Millard’s technique) with 1.5 years of the palate with a Y buccinator flap, and rhinoplasty after puberty. He underwent only orthodontic treatment, had a normal bite and voice.

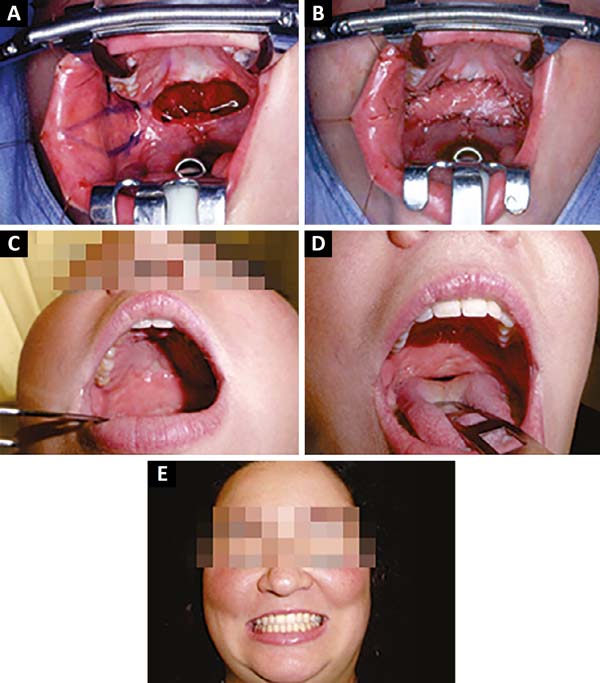

The patient in figure 10 A-B-C-D-E, a tourism businesswoman, underwent a secondary stretching after correction of the soft palate (incomplete post-foramen fissure) with the simple approach technique, resulting in fistula, which was corrected, and palate elongation. He underwent orthopedic, and speech and hearing treatments to attain normal voice and bite.

DISCUSSION

The buccinator muscle flap, besides its uses in fissures and fistulas, can be used in any situation in bloody intrabuccal areas, such as tumor resections, osteomyelitis, or traumatic losses. Two flaps can be used simultaneously, one for the nasal lining and the other for the oral mucosa. In case of failure of one, the other can still survive.

In cases of postoperative fistula, the tissues become fibrous, rigid, and retractable, making it impossible to obtain adequate, movable, and long palates with good function without the use of new tissues such as the flap described.

Irrigation of the buccinator muscle with its anterior pedicle can repair labial defects of the mucosa, traumatic wounds, or tumor post-resection sites21.

Using the flap leaves the nasal lining and flap sutures in different positions, making it difficult for new fistulas to appear.

The transposition of the flap and 180º rotation behind the maxillary tuberosity always leaves a cicatricial bridle that does not lead to functional consequences. It can be corrected at any time after the integration of the flap with a mini zetaplasty.

It was described in 1989 that the donor area of the flap was not modified, but one of the patients contacted (Figure 8F) presented a reduction in the extensibility of the cheek, without causing any oral function impairment or maxillo-mandibular alterations. His medical record indicated that the flap was wide, which can be seen in figure 8C, and that it was difficult to close the donor area.

In the original description, he commented on the lymphatic edema and the muscle volume, and that the massage caused by the movements of the tongue reduced it, which was verified to be true by the other patients contacted.

Maxillary growth was practically normal in the primary patients contacted, where the none of the palatal flaps were detached and only orthodontic treatment was required. One patient (Figure 6A-E) did not undergo any treatment, and the fissured side evolved with collapse of the arch on that side, which was already visible in the preoperative photograph in childhood.

As for speech, even those who did not receive speech therapy presented minimal changes in their voices22. This was demonstrated in 6 cases that were surgically treated using the described technique. The patient in figure 11A-B-C-D-E-F-G underwent surgery using the traditional techniques17,18 and had 27-year postoperative results, without maxillary orthodontic and orthodontic treatments, which were the standard treatment before the advent of the buccinator muscle flap. In addition to dental misalignment and hypodevelopment of the maxilla, he had great difficulty speaking due to nasal exhaust.

The attempt contact these patients started from the time of entry into plastic surgery residency at the Base Hospital of the State Medical School of São José do Rio Preto. The patient in figure 9A-B-C-D-E was attended to by the author from the first day of life.

Historically, the study of flaps started from a colloquial debate between friends, the author and Chem23, when the former manifested the impossibility of correcting palatal fistulas with a microsurgical flap from the pedicle artery of the foot pedicle owing to the difficulties that the technique presented for surgeons who did not perform microsurgery, as the author himself. He expressed the need to look for other solutions, complementing previous studies that sought to obtain better function and closure of the palate with minimum sequelae24-28.

CONCLUSION

Although statistically insignificant, the verification of cases over a mean period of 27 years shows that the 6 patients contacted had normal or near-normal maxillary growth and almost normal speech even without adequate phono-audiological treatment. One patient had poor extensibility of the cheek because the flap was too wide.

REFERENCES

1. Bozola AR, Gasques JA, Carriquiry CE, Cardoso de Oliveira M. The bucinator musculomucosal flap: anatomic studyand clinical application. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1989;84(2):250-7. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00006534-198908000-00010

2. Bozola AR, Cardoso de Oliveira M, Sanches VM, Gasquez JAL, Marchi MA, Kurimori MS. Uso do retalho miomucoso de músculo bucinador na correção de fissuras palatinas. Rev Soc Bras Cir Plast. 1986;1(1)7-13.

3. Goss CM, ed. Gray' Anatomy of the Human Body, 28th ed. Philadelphia: Lea&Febiger, 1966. p. 388-390.

4. Charp A. Muscles peauciers do cou et de latete. Poirier P, Charpy A, eds. Traité d' Anatomie Humaine, Volume 2. Paris: Masson; 1901. p. 355-63.

5. Romanes GJ, ed. Cunningham's Textbook of Anatomy. 10th ed. London: Oxford University Press, 1964. 874 p.

6. Bourgery J, Jacob NH. Traite complet de l'anatomie de l'homme. Volume 4. Paris: Delaunay, 1851. p. 75-6, 80-1.

7. Patten MB. In: Schaeffer JP, ed. Morris' Human Anatomy. 10th ed. Philadelphia: Blakiston;1942. P. 611-23.

8. Paturet G. Traite d'anatomie humaine. Volume. 3. Paris: Masson; 1958. p. 288, 316-7.

9. Hollinshead WH. Textbook of Anatomy. New York: Hoeber; 1962. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF02616407

10. Poirer P. Angeoilogie. In: P Poirier P, Charpy A, eds. Traité d' Anatomie Humaine, Volume 2. Paris: Masson; 1901. p. 674-8.

11. Salmon M. Les Artères de la Peau. Paris: Masson; 1936. p. 106-7.

12. Rhoton AL, Lineweaver W. Quoted by Freeman BS. In: Converse JM. Reconstructive Plastic Surgery, Volume 3. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1977. p. 1777.

13. McCormack LJ, Cauldwell EW, Anson BJ. The surgical anatomy of the facial nerve with special reference to the parotid gland. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1945;80:620.

14. Le Quang C. Le plexus génien du nerf facial. Ann Chir Plast Esthét. 1976;21:5-15.

15. Hovelacque A. Anatomie des nerfs craniens et rachidiens et du système grand sympatique chez l'homme. Paris: Doin; 1927. 185 p.

16. Bozola AR, Gasquez JAL. Retalhos In: Hochberg J, ed. Bucinador. Cap 24, 419/457. São Paulo: Medsi 1990. p. 419-57.

17. Von Langenbeck BRK. Operation der angeborenen totale spaltung des harten gaumens nach einer neue methode. Dtsch Klinik. 1861;13:231.

18. Veau V. Division Palatine, Anatomie, Chirurgie, Phonetique. Paris: Masson; 1931.

19. Furlow LT Jr. Cleft palate repair by double opposing Z-plasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1986;78(6):724-38. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00006534-198678060-00002

20. Millard DR Jr. The primary camouflage of the unilateral harelip. In: Skoog T, Ivy RH, eds. Transactions of the 1st International Congress of Plastic Surgery. 1955; Stockholm, Sweden. Baltimore, Willians & Wilkins; 1957. p. 160-6.

21. Gomes, PRM, Rosique RG, Rosique MJF, Mélega JMA. Retalho anterior de músculo bucinador para correção de fístula oronasal com acesso intra-oral. Rev Bras Cir Craniomaxilofac. 2008;11(4):168-71.

22. Raposo do Amaral CA. Uso do retalho miomucoso do músculo bucinador bilateral para o tratamento de insuficiência velofaríngea: avaliação preliminar. Rev Bras Cir Plast. 2013;28(3):455-61.

23. Chem RC, Franciosi LFN. Dorsalis pedis free flap to close extensive palate fistulae. Microsurgery. 1983;4(1):35-9. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/micr.1920040111

24. Guerrero-Santos J, Altamirano JT. The use of lingual flaps in repair of fistulas of the hard palate. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1966;38(2):123-8. PMID: 5913181 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00006534-196608000-00007

25. Culf N, Chong JK, Cramer LM. Different Surgical Approach to Secondary Velopharyngeal Imcompetence. In: Georgiade HG, Hagerty FF, eds. Symposium on Manegement of Cleft Lip and Palate and Associated Deformities. St. Louis: Mosby; 1974.

26. Jackson IT. Closure of secondary palatal fistulae with intra-oral tissue and bone grafting. Br J Plast Surg. 1972;25(2):93-105. PMID: 4554003 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0007-1226(72)80028-6

27. Kaplan EN. Soft palate repair by levator muscle reconstruction and a buccal mucosal flap. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1975;56(2):129-36. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00006534-197508000-00002

28. Maeda K, Ojimi H, Utsugi R, Ando S. A T-shaped musculomucosal buccal flap method for cleft palate surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1987;79(6):888-96. PMID: 3588727 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00006534-198706000-00006

1. Hospital de Base, Faculdade Estadual de

Medicina de São José do Rio Preto, São José do Rio Preto, SP,

Brazil.

Corresponding author: Antonio Roberto

Bozola

Av. Brigadeiro Faria Lima, 5416 - Vila São Pedro

São José do

Rio Preto, SP, Brazil Zip Code 15090-000

E-mail: ceplastica@hotmail.com

Article received: November 24, 2017.

Article accepted: February 19, 2018.

Conflicts of interest: none.

Read in Portuguese

Read in Portuguese

Read in English

Read in English

PDF PT

PDF PT

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to Cite

How to Cite

Mendeley

Mendeley

Pocket

Pocket

Twitter

Twitter