Original Article - Year 2016 - Volume 31 - Issue 2

The impact of care actions on the perception of the quality of the Single Health System (SUS), Brazil: a cross-sectional study

O impacto de ações assistenciais na percepção da qualidade do Sistema Único de Saúde (SUS), Brasil: um estudo transversal

ABSTRACT

INTRODUCTION: Non-melanoma skin cancer is the most prevalent cancer in Brazil. Surgical resection is one of the pillars of management, and care actions, such as surgical task forces, are one way to reduce treatment waiting time.

METHODS: In this research, we conducted a cross-sectional study with 40 patients; 20 of whom were treated by a surgical task force and 20 were controls. Epidemiological data were collected in addition to answers to nine questions related to the quality of the Single Health System (SUS in Portuguese).

RESULTS: A significant difference was observed in responses related to the waiting time for surgery in the SUS (p < 0.05).

CONCLUSION: One can observe an improvement in the perception of patients, with regard to the SUS, when included in care actions.

Keywords: Skin Cancers; Plastic Surgery; Public Health; Brazil.

RESUMO

INTRODUÇÃO: O tumor de pele não melanoma é o câncer mais frequente no Brasil. A ressecção cirúrgica é um dos pilares do manejo e ações assistenciais como mutirões de cirurgias são formas de reduzir o tempo de espera por tratamento.

MÉTODOS: Nesse trabalho, conduziu-se um estudo transversal com 40 pacientes, 20 deles participantes de mutirão e 20 controles. Coletaram-se dados epidemiológicos, além de nove perguntas relacionadas à qualidade do Sistema Único de Saúde (SUS).

RESULTADOS: Observou-se diferença significativa entre as respostas relacionadas ao tempo de espera por cirurgias no SUS (p < 0,05).

CONCLUSÃO: Pode-se verificar melhora na impressão dos pacientes em relação ao SUS quando incluídos em ações assistenciais.

Palavras-chave: Neoplasias cutâneas; Cirurgia plástica; Saúde pública; Brasil.

Non-melanoma skin cancer is the most prevalent cancer in Brazil, in both sexes, and was responsible for more than 180,000 new cancer cases in 20141. Early detection is critical to proper treatment, given the possibility of sequelae that treatment of advanced lesions can generate2. Moreover, individuals with a personal history of skin cancer have an increased risk of new lesions, and up to 40% of patients with a history of skin cancer develop other cancers within a period of five years3. Surgical resection is one of the pillars of treatment, and the frequent facial commitment makes plastic surgery a player in the healing of these patients4.

Research performed by the Datafolha institute, with 2418 people, indicates that the attendance by the Single Health System (SUS in Portuguese) has a negative image for 87% of the Brazilian population5. The most critical points are related to access, and to the waiting time for primary care (including surgeries). With regard to the quality of service, 70% of those who sought the services of the SUS claimed to be dissatisfied. Add to that the fact that 57% of the population believes that health in Brazil should be treated as a priority by the Federal Government, and one can see that the image of health care is currently going through a delicate phase.

Care actions, such as surgical task forces, are used as tools by service providers to reduce waiting lists in a longstanding, overloaded system. However, the impact that these efforts have on the image of the Single Health System, and the potential that events of this nature have as an opinion modifier, is not known.

OBJECTIVE

The objective of this study was to evaluate the difference in the perception of patients treated surgically for skin cancer by routine procedures or in surgical task forces, regarding the quality of care in the Single Health System.

METHODS

A cross-sectional study was conducted with 40 patients, 20 of whom were treated by surgical task forces for skin cancer surgeries, performed by the Residency of Plastic Surgery at the Hospital Nossa Senhora da Conceição, on May 16, 2015, in the city of Porto Alegre, RS. The other 20 patients were selected sequentially from the waiting list of surgeries of the same service, during the months of June and July 2015. The inclusion criteria for both arms were patients with pre-operative resectable skin lesions, and the cognitive state to understand the questionnaires. Patients who could not understand the questions, did not reply in entirety, or who refused to participate in the study were excluded.

The questionnaires administered to the patients were developed by the research team, and the following data were collected: age, previous history of skin cancer, waiting time since the referral to Plastic Surgery, and site affected. The nine questions, related to the quality of care, were as follows: (1) What do you think of using surgical task forces in the treatment of skin cancer? (2) What do you think of surgical task forces as a way of improving the SUS? (3) What do you think of the waiting time for surgery, in general, in the SUS? (4) What do you think of the waiting time for surgery of skin cancer in the SUS? (5) How do you see the structure (rooms, offices) provided by the SUS? (6) What do you think of the doctors that attend in the SUS? (7) What do you think of the results of surgeries performed in the SUS? (8) What do you think of the manner of referral to specialists in the SUS? (9) How do you see the quality of the Single Health System service?

Objective responses were collected with the use of a Likert scale, with possible answers being "Very bad," "Bad," "Fair," "Good," and "Very good." The sample size was calculated by taking into account the number of patients participating in the surgical task force and adding the same number of controls. Analysis of surgery waiting times was performed by the Mann-Whitney U test. The comparison of the answers to the questionnaire of the two groups was performed using the chi-square test, with a significance of p < 0.05. All patients signed a Free and Informed Consent Form, and the study was conducted in accordance with the precepts of the Helsinki Declaration of the World Medical Association.

RESULTS

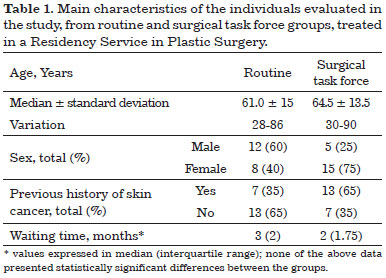

The clinical characteristics of the sample surveyed are presented in Table 1, and none of the data presented a statistically significant difference between the surgical task force and routine groups. Note that the waiting time between referral to surgery and the procedure also did not differ between the two groups.

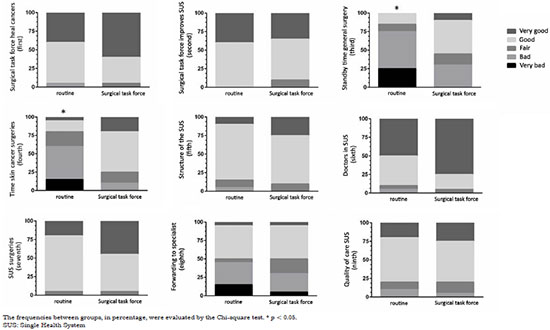

With regard to the questions administered, a statistically significant difference was observed between the answers to the third and fourth questions. In question number three (What do you think of the waiting time for surgery, in general, in the SUS?), the following distribution was recorded (surgical task force/routine): very bad 0/5; bad 6/10; fair 3/2; good 9/3; very good 2/0 (p = 0.024). In the fourth question (What do you think of the waiting time for surgery of skin cancer in the SUS?), the following distribution was recorded (surgical task force/routine): very bad 0/3; bad 2/9; fair 3/4; good 11/3; very good 4/1 (p = 0.007). The other questions showed no statistically significant differences between groups, and their distribution is represented in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Responses of patients from the routine or collective initiative groups in accordance with the modified Likert scale.

DISCUSSION

One of the main factors that lead to the dissatisfaction of patients with the SUS is the waiting time for primary care5. The achievement of care actions - such as a surgical task force - aims to reduce this time, increasing the possibilities of treatment for patients affected by malignant skin cancers and, consequently, improve their prognosis.

Analysis of the data obtained with the study reveals the impact on the perception of patients on the SUS, when included in care actions similar to those performed herein. When comparing both groups, with similar waiting time for surgeries, there is a divergence of opinion about this same time for surgeries in the SUS (questions 3 and 4).

Of the patients included in the surgical task force, combining the two questions, 65% were satisfied with the waiting time (very good and good), whereas 67.5% of those not included in the surgical task force were dissatisfied (very bad and bad). Therefore, the change in the perception of waiting time, through the care action, is evident. It is important to mention that one limitation of the study, and possible source of bias, was that the data collection was performed by members of the Plastic Surgery service, which may have influenced the responses in both arms of the study.

Taking into account the increase in the incidence of skin cancer6 and the consequent increase in treatment costs7, programs that allow its early diagnosis and treatment, such as the aforementioned care actions as well as educational and surveillance programs, are an added value for the reduction in costs of the public health system. For this, we have the availability of different medical specialties trained and empowered to manage this cancer8, in addition to the low cost of the various types of treatment available, regardless of the specialty which will attend the patient9.

CONCLUSION

Given the increase in spending proportional to the degree of progression of the disease10, we can conclude that care actions, such as that promoted in our service, included in a set of educational actions and possible surveillance programs of skin cancer, can strongly contribute to the reduction of expenses of the Single Health System, as well as the improvement of the perception of this system in the eyes of patients.

COLLABORATIONS

GB Analysis and/or data interpretation; statistical analysis; final approval of the manuscript; conception and design of the study; completion of operations and/or experiments; writing of the manuscript or critical review of its contents.

FAZ Completion of operations and/or experiments.

KGDR Completion of operations and/or experiments.

RC Completion of operations and/or experiments.

LSS Completion of operations and/or experiments; writing of the manuscript or critical review of its contents.

MDV Completion of operations and/or experiments.

AHPN Completion of operations and/or experiments.

VSL Final approval of the manuscript; conception and design of the study; completion of operations and/or experiments.

REFERENCES

1. Instituto Nacional de Câncer José Alencar Gomes da Silva (Brasil). Estimativa 2014. Incidência de Câncer no Brasil. Coordenação de Prevenção e Vigilância. Rio de Janeiro: INCA; 2014. 124p.

2. Rogers-Vizena CR, Lalonde DH, Menick FJ, Bentz ML. Surgical treatment and reconstruction of nonmelanoma facial skin cancers. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;135(5):895e-908e. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0000000000001146

3. Karagas MR, Stukel TA, Greenberg ER, Baron JA, Mott LA, Stern RS. Risk of subsequent basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma of the skin among patients with prior skin cancer. Skin Cancer Prevention Study Group. JAMA. 1992;267(24):3305-10. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.1992.03480240067036

4. Bath-Hextall F, Bong J, Perkins W, Williams H. Interventions for basal cell carcinoma of the skin: systematic review. BMJ. 2004;329(7468):705. PMID: 15364703 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.38219.515266.AE

5. Datafolha, Conselho Federal de Medicina, Associação Paulista de Medicina. Opinião dos brasileiros sobre o atendimento na área da saúde. Julho de 2014. [Acesso 15 Abr 2016]. Disponível em: http://portal.cfm.org.br/images/PDF/apresentao-integra-datafolha203.pdf

6. Wysong A, Linos E, Hernandez-Boussard T, Arron ST, Gladstone H, Tang JY. Nonmelanoma skin cancer visits and procedure patterns in a nationally representative sample: national ambulatory medical care survey 1995-2007. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39(4):596-602. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/dsu.12092

7. Guy GP Jr, Machlin SR, Ekwueme DU, Yabroff KR. Prevalence and costs of skin cancer treatment in the U.S., 2002-2006 and 2007-2011. Am J Prev Med. 2015;48(2):183-7.

8. Romero PC, Kinney MA, Taylor SL, Levender MM, David LR, Goldman ND, et al. Nonmelanoma skin cancer treatment training varies across different medical specialists. J Dermatolog Treat. 2013;24(3):215-20. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/09546634.2012.671916

9. Chirikov VV, Stuart B, Zuckerman IH, Christy MR. Physician specialty cost differences of treating nonmelanoma skin cancer. Ann Plast Surg. 2015;74(1):93-9. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/SAP.0b013e31828d73f0

10. Mudigonda T, Pearce DJ, Yentzer BA, Williford P, Feldman SR. The economic impact of non-melanoma skin cancer: a review. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2010;8(8):888-96.

1. Hospital Nossa Senhora da Conceição, Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil

2. Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil

Institution: Hospital Nossa Senhora da Conceição, Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil.

Corresponding author:

Guilherme Barreiro

Av. Borges de Medeiros, 3200, Ap 1802 - Praia de Belas

Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil Zip Code 90110-150

E-mail: plasticabarreiro@gmail.com

Article received: September 14, 2015.

Article accepted: April 10, 2016.

Conflicts of interest: none.

Read in Portuguese

Read in Portuguese

Read in English

Read in English

PDF PT

PDF PT

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to Cite

How to Cite

Mendeley

Mendeley

Pocket

Pocket

Twitter

Twitter