Original Article - Year 2016 - Volume 31 -

The use of adhesion sutures to minimize the formation of seroma following mastectomy with immediate breast reconstruction

Estudo do uso de pontos de adesão para minimizar a formação de seroma após mastectomia com reconstrução imediata

ABSTRACT

INTRODUCTION: Breast cancer is the most common cancer among women in Brazil. With the advent of immediate breast reconstruction, several techniques with many benefits for patients were introduced, including the use of alloplastic materials. A seroma is a frequent complication in all surgical procedures, and several methods have been developed to prevent it, which include the use of vacuum suction drains and adhesion sutures, as proposed by Baroudi. This study aims to demonstrate the advantages of the use of adhesion sutures between subcutaneous tissue and the muscle flap in breast reconstruction using implants or expanders after mastectomy.

METHODS: Patients who underwent breast reconstruction using implants or expanders after mastectomy were followed up for 5 months . Patients were divided into a control group treated without adhesion sutures, and a Baroudi group treated with adhesion sutures.

RESULTS: A statistically significant difference was observed with the use of adhesion sutures, with a lower incidence of seroma, reduced drain permanence, less need to return to the clinic, and faster recovery. There was no increase in surgical complications.

CONCLUSION: The use of adhesion sutures in breast reconstruction is an effective option that reduces the occurrence of seroma and associated complications, resulting in faster recovery and return to normal activities.

Keywords: Mastectomy; Seroma; Postoperative complications; Drainage; Prostheses and implants.

RESUMO

INTRODUÇÃO: O câncer de mama é o tipo mais frequente de câncer entre as mulheres no Brasil. Com o advento das reconstruções mamárias imediatas, várias técnicas começaram a ser utilizadas. O uso de materiais aloplásticos é uma delas e, quando bem indicados, trazem inúmeros benefícios às pacientes. O seroma é uma complicação cirúrgica frequente e comum em todos procedimentos cirúrgicos, e, para preveni-lo, várias opções são conhecidas, como o uso de drenos de sucção a vácuo e os pontos de adesão propostos por Baroudi. Visamos demonstrar o benefício dos pontos de adesão entre o tecido subcutâneo resultante da mastectomia e o retalho muscular nas reconstruções mamárias com uso de próteses ou expansores.

MÉTODOS: Foram selecionadas pacientes submetidas à reconstrução mamária após mastectomia, com uso de próteses ou expansores num período de 5 meses. Foram formados dois grupos, sendo o grupo controle as pacientes em que não foram utilizados os pontos de adesão, e o grupo Baroudi composto pelas pacientes em que os pontos de adesão foram utilizados.

RESULTADOS: Encontramos um resultado estatisticamente significante no uso dos pontos de adesão, levando a menor ocorrência de seroma e tempo de permanência do dreno menor, bem como menor necessidade de retornos ao consultório e recuperação mais rápida. Não houve aumento das complicações cirúrgicas.

CONCLUSÃO: O uso dos pontos de adesão para reconstrução de mama é uma opção eficaz que reduz a ocorrência de seroma e as complicações associadas a ele, proporcionando uma retomada mais rápida às atividades habituais das pacientes.

Palavras-chave: Mastectomia; Seroma; Complicações pós-operatórias; Drenagem; Próteses e implantes.

According to data reported by the INCA (National Institute of Cancer), 57,120 new cases of breast cancer were expected in Brazil in 20141 (accounting for 22% of all types of cancer), with an estimated rate of 56.09 cases per 100,000 women; breast cancer was responsible for the deaths of 13,225 women in 20112. Excluding non-melanoma skin cancers, breast cancer is the most common cancer among women in Brazil and the second most common worldwide. Surgery is the primary treatment method, and both partial and total mastectomies can lead to complications, such as seroma, surgical wound dehiscence, or lymphedema.

Historically, breast reconstructions were delayed, as these were major surgeries that often influenced adjunctive treatment, thus delaying chemotherapy, due to either prolonged postoperative recovery or the high frequency of complications. Over time, the benefits of immediate breast reconstruction became apparent. The ability to perform breast reconstruction in combination with mastectomy reduces anesthetic exposure and treatment costs; combined with the postoperative advantages, these result in decreased reconstructive surgical time and an improved psychosocial experience for the patient.

There are several options for immediate breast reconstruction; over time, the indications have been modified. For some time, use of autologous tissues such as the transverse rectus abdominis muscle (TRAM) flap or the latissimus dorsi was the first choice, but this may no longer be possible in certain patients. Women with a low body mass index (BMI), who do not have enough donor area to create musculocutaneous flaps, may prefer less complex reconstruction; some patients wish to avoid the added morbidity in the donor area, and the increased hospitalization and postoperative recovery time. Comorbidities also limit the use of autologous tissue. In these patients, the use of implants or expanders in breast reconstruction may be the best option.

Breast reconstruction with expanders or silicone implants is an excellent choice in appropriately selected patients. It can be performed immediately, and sometimes even in the same surgery. These techniques evolved significantly since the early 60s, with the introduction of silicone implants, until the 80s, with studies published by Radovan3. In addition to significant improvements in surgical technique, progress has been made by implant manufacturers, who began to produce implants made of the most sophisticated materials to provide better and more natural results, as well as lower rates of capsular contracture4.

When compared to other techniques, the possible advantages of breast reconstruction with implants include the relative ease of the technique, absence of skin changes such as color and texture absence of complications in the donor area of the flap, lesser scars, and faster postoperative recovery5.

The main limitation to the use of implants for immediate breast reconstruction is inadequate coverage of soft tissue. With the advent of skin-sparing and subcutaneous mastectomy, immediate breast reconstruction and the use of implants became the first option for selected patients4. After mastectomy, a plane is created below the pectoral muscle for the positioning of the implant. Additional procedures, such as the use of serratus muscle flaps and rectus abdominis fascia, could optimize the coverage of the implants.

Despite the great efficiency of these techniques, some local complications persist, and the incidence is generally higher in immediate reconstruction. These include a higher risk of seroma formation, skin necrosis, extrusion and exposure of the implant, and malfunction and leakage/deflation of the valve (the last three being related to the use of expanders).

An important morbidity factor is the appearance of a seroma at the mastectomy site; this is the most frequent complication. The incidence varies from 18 to 89% according to the literature6, even when a vacuum suction drain is used. The maintenance of a suction drain for long periods does not prevent the occurrence of seroma. Treatment can include repeated and painful puncture, causing great discomfort to the patient, in addition to the possibility of accidental perforation of the thoracic wall, leading to pneumothorax formation, or even of the implant.

In recent decades, different laminar or vacuum suction drains have been used in an attempt to prevent the formation of seromas, although several papers have described their occurrence during the postoperative period in surgeries with large detachments. An interesting solution to this problem was reported by Baroudi and Ferreira, and refers to the use of adhesion sutures in abdominoplasty and other dissections, thus eliminating dead space and the possibility of a seroma or hematoma7. The literature suggests that use of adhesion sutures between the subcutaneous tissue and detached flap might reduce the formation of seromas in surgery with large detachments8-13.

OBJECTIVE

The objective of this study is to evaluate the incidence of postmastectomy seroma with immediate reconstruction when adhesion sutures (Baroudi sutures) are used, by measuring vacuum suction drainage. Therefore, we studied the daily output of the drain and the incidence of seroma, comparing patients with and without adhesion sutures.

METHODS

This is a prospective cohort study conducted at the Plastic Surgery Service of the Daher Hospital in the city of Brasília, DF. The study period was 10 months, from August 2014 to May 2015, and the patients were divided into two groups according to whether or not adhesion sutures were used in breast reconstruction surgery.

The sample was intentionally not random and consisted of patients who underwent total mastectomy for breast cancer, with immediate reconstruction using an implanted prosthesis or temporary expander. A total of 44 surgeries (8 bilateral) were performed in 36 patients. All patients underwent mastectomy by the same team of breast surgeons and reconstruction by the same plastic surgery team.

Patients who underwent mastectomy followed by reconstruction using an implant (prosthesis, expander, or a latissimus dorsi flap with prosthesis) were included. Patients who underwent reconstruction with a TRAM flap and those who underwent late reconstruction were excluded.

This study followed the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

In the group that received adhesion sutures, a pectoralis major muscle flap, serratus flap, or rectus sheath were used to produce the plane for positioning of the implant. This was followed by closure of the muscle plane with Vicryl 2-0 interrupted sutures and approximation of the subcutaneous tissue to the muscle flap with adhesion sutures. The redundant tissue was then moved from the lateral to medial breast quadrants, and vacuum drainage was applied using a 6.4-mm drain.

In the control group, adhesion sutures were not placed between the redundant subcutaneous tissue and muscle flap. All patients were instructed to manage the drain postoperatively, maintaining the permanent vacuum and emptying the drain at the same time, once a day. They were also instructed to record the daily output until the time of drain removal. This occurred when the drain had a flow rate of less than 40 ml in 24 hours. The flow was measured using a standard graduated collection bag.

The patients had outpatient follow-up. The drain was removed by the medical team. The presence of seroma and need for puncture drainage were evaluated weekly or as needed.

The statistical analysis was performed with Student's t test, the chi-squared test, or Fisher's exact test, as appropriate.

RESULTS

The data recorded included age, BMI, type of reconstruction, breast size, presence of comorbidities (hypertension, diabetes, hypothyroidism, and smoking), and the use of preoperative chemotherapy.

The groups were homogeneously distributed according to age. The average age was 54.04 years (standard deviation [SD] 11.6) in the control group, and 48.90 years (SD 10.08) in the group with adhesion sutures, with p of 0.214. The average BMI was 23.55 kg/m2 (SD 2.99) in the control group, and 25.01 kg/m2 (SD 2.81) in the group with adhesion sutures, with p of 0.103.

The correlation between the incidence of seroma and the use or nonuse of Baroudi's technique, and the patient comorbidities are shown in Table 1. The values are expressed as mean and SD for normally distributed data and compared by Student's t-test. Categorical data are presented as the number of patients and were compared by the chi-squared or Fisher's exact test, as appropriate. The only comorbidity related to the occurrence of seroma that was statistically significant was hypertension, with a p of 0.031. The other comorbidities evaluated in the sample were not statistically significant (Table 1).

Patients reconstructed using implants were more likely to form a seroma than those reconstructed with expanders or a latissimus dorsi flap, with p of 0.013.

The variables studied were drain permanence time, occurrence of seroma or other complications (necrosis, minor or major infection, dehiscence, and capsular contracture), number of postoperative returns, and need for surgical reintervention.

The number of returns to the clinic was statistically significant (p = 0.001). A total of 124 returns were recorded for patients in the control group, and 77 for the group with adhesion sutures.

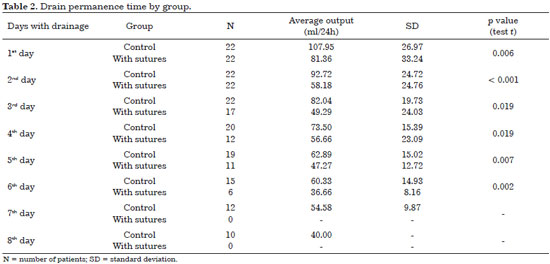

The average daily drain output until removal (standardized as flow below 40 ml/24 h) is shown in Table 2. The drain remained longer in the control group than in patients with adhesion sutures (6.45 days vs. 4.9 days, respectively). The average daily output and drain permanence time for the groups studied are shown in Table 2.

We observed 3 cases of seroma in the group with adhesion sutures and 9 in the control group (Figure 1). This difference was statistically significant, with p of 0.042.

Figure 1. Seroma occurrence in the different groups.

Other complications included hematomas, surgical wound dehiscence, minor infections (resolved with oral antibiotics and local care), and nipple-areolar complex necrosis. The latter occurred in 5 cases in the control group, but none in the Baroudi group, with p of 0.018. Capsular contractures were not observed during the study. Complications are shown in Table 3 (categorical data are presented as the number of patients and were compared by the chi-squared test). Excluding seroma, none of the complications observed were directly correlated with the objective of this study.

DISCUSSION

Seroma is characterized by the presence of serous fluid accumulation in the dead space between areas detached during surgery. Treatment may include puncture and aspiration, or even surgery. The formation of a seroma is evident on clinical examination, with bulging and tissue fluctuance, and can be confirmed by ultrasound.

The origin of the tissue fluid is multifactorial, and includes drainage from lymphatic and blood vessels that normally drain interstitial fluids. A statistically significant risk factor in our series was the presence of hypertension (p = 0.031). As reported by Meeske et al.14, high blood pressure can be a risk factor for the occurrence of seroma because increased blood flow might increase lymphatic flow to the tissues.

In addition, the size of the dissected area may facilitate the accumulation of secretions. The composition of seroma fluid is very similar to that of lymph, with respect to total protein, lactate dehydrogenase, and cholesterol, which are present at high levels when compared to their levels in blood. The number of leukocytes in the seroma fluid is low, but there is a high percentage of neutrophils, both from blood and lymph.

Many strategies have been used to minimize or prevent seroma, including external pressure, positioning of preventive drains, and use of talc. Treatment may include prolonged or repeated drainage, fibrin glue, sclerotherapy with tetracycline hydrochloride, diuretics, and adhesion sutures7,13,15-17.

The literature suggests that adhesion sutures between the subcutaneous tissue and the aponeurosis of subjacent muscle might reduce the formation of seroma in abdominoplasties7-9,11-13,18. The use of vacuum suction drainage in combination with adhesion sutures, while closing the detachment, reduces dead space and allows the superior flap to remain in contact with the inferior surface. This facilitates adherence and reduces seroma formation13,15.

The development of a postoperative seroma increases morbidity, with the need for repeated puncture and the possibility of pneumothorax, besides the risk of infection and perforation of the implant. The maintenance of suction drains for long periods does not avoid the appearance of seroma19.

Stehbens20 attributed secretion or seroma formation after mastectomy to closed vacuum drainage. This was considered an impediment to healing, favoring the accumulation of secretions. Therefore, fixation of the cutaneous flap of the mastectomy to the thoracic wall was recommended, in order to reduce the dead space.

In another study, Juaçaba and Juaçaba21 compared two groups of patients who underwent mastectomy and cutaneous flap fixation to the thoracic wall. Vacuum drainage was used in only one group. The drain proved unnecessary, as secretion accumulation was similar in both groups.

Pogson et al.22 searched the global literature to determine the advantages and disadvantages of techniques used to treat seroma in mastectomy patients. The conclusion was that mechanical reduction of dead space with adhesion sutures and delaying shoulder physiotherapy reduced the incidence of seroma. Removal of the suction drain 48 hours after surgery, regardless of the volume drained, did not increase the rate of seroma formation.

Another study23 showed no significant differences with respect to postoperative complications, especially seroma, between two groups of mastectomy patients; closure of dead space was performed in the first group without the use of a drain, and the surgical wound was simply closed in the second group, with use of vacuum drainage.

In our experience, the rate of seroma formation was higher when adhesion sutures were not used between the muscle flap and redundant subcutaneous tissue (40% vs. 13%). This corroborates the findings of other studies. The decreased number of cases with seroma formation may be related to the use of adhesion sutures, as widely reported in the literature for other surgical sites. Moreover, the use of adhesion sutures statistically significantly reduced the daily drain output and permanence time (6.45 days in the control group vs. 4.9 days in the group with adhesion sutures).

Another frequent complication is restriction of arm movement and delay in recovering range of motion. Mastectomy patients usually require physical therapy due to the contractures of the shoulder girdle caused by surgical trauma, radiotherapy, extreme positioning of the upper limb during surgery, potential retraction, muscle-tendon and joint injuries, and fear of pain, among other factors.

There is no consensus on the ideal range of motion of the shoulder in the first postoperative days. Some authors suggest that movement should be limited to flexion and abduction of 40° in the first two postoperative days, 45° on the third day, flexion to 45-90° degrees and abduction to 45° on the fourth day, and free movement from the seventh day on. Other authors suggest that the movement should be limited to 90° in the first 15 days after surgery. Some authors still suggest total movement restriction during the first five to seven days. This limitation aims to minimize the lymphatic complications caused by axillary dissection24-27.

The decrease in shoulder range of motion affects over 50% of women with mastectomies in the postoperative period. This interferes with their quality of life, causing functional limitations and work constraints28. Sugden et al.29 reported that half of the women who underwent lymphadenectomy associated with mastectomy or quadrantectomy due to breast cancer had limitation of at least one shoulder movement 18 months after surgery. Nagel et al.30 describes shoulder movement restriction in 24% of women who underwent axillary emptying.

Rietman et al.31, in a systematic review, found that women had difficulty performing activities of daily living after breast cancer surgery. One-fifth reported difficulty with upper body dressing, 18% with hooking a bra, and 72% with closing a zipper on the back; 16% could not lift their hands to the top of the head and 29% had difficulty lifting weight. In general, these limitations tend to resolve by 42 days after surgery28.

Our patients always started therapy on the seventh postoperative day, and were instructed to limit the range of motion of the upper limbs to 90º until the 15th postoperative day. In general, all recovered movement without limitations after a postoperative period of 60 days with the aid of physical therapy. Only 6 patients (27%) (4 in the control group and 2 in the group with adhesion sutures) among the 44 studied had a slight delay in recovery after the 30th postoperative day. This was in agreement with the data in the literature, but not statistically significantly different from our findings. This delay in recovery seems to be related to the technique used for reconstruction, even though we know that the presence of seroma delays full recovery. Therefore, this delay limits comfort and limb mobility on the affected side.

Adhesion (Baroudi) sutures used between subcutaneous tissue and the pectoralis major muscle flap in breast reconstruction after mastectomy are important and effective tools for decreasing the occurrence of postoperative complications, including seroma and its comorbidities.

The technique is easily and rapidly performed, has a low rate of complications, and provides statistically significant results, such as reduction in daily drainage and earlier drain removal.

The decreased occurrence of seroma leads to a reduced number of returns to the clinic, thus resulting in lower costs, reduced exposure to secondary invasive procedures, and more rapid recovery, as well as an earlier return to usual activities.

COLLABORATIONS

MCC Planning and study design; review of critical content; performance of experiments; analysis and/or data interpretation; final approval of the manuscript.

IRJ Planning and study design; review of critical content; performance of experiments; analysis and/or data interpretation; final approval of the manuscript.

RQL Critical review of content.

CMA Critical review of content.

LGM Critical review of content.

LMCD Critical review of content.

DASS Critical review of content.

MCAG Critical review of content.

JCD Critical review of content.

FTM Statistical analysis.

REFERENCES

1. Instituto Nacional de Câncer José Alencar Gomes da Silva (Brasil). Estimativa 2014. Incidência de Câncer no Brasil. Coordenação de Prevenção e Vigilância. Rio de Janeiro: INCA; 2014. 124p.

2. Sistema de Informações sobre Mortalidade - SIM - DATASUS [Acesso 10 Abr 2016]. Disponível em: http://tabnet.datasus.gov.br/cgi/sim/Consolida_Sim_2011.pdf

3. Radovan C. Breast reconstruction after mastectomy using the temporary expander. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1982;69(2):195-208. PMID: 7054790 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00006534-198202000-00001

4. Roostaeian J, Pavone L, Da Lio A, Lipa J, Festekjian J, Crisera C. Immediate placement of implants in breast reconstruction: patient selection and outcomes. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;127(4):1407-16. PMID: 21460648 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0b013e318208d0ea

5. Beasley ME. Two-stage expander/implant reconstruction: Delayed. In: Spear SL, ed. Surgery of the Breast: Principles and Art. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1998.

6. Ribeiro LFJ, Freitas Júnior R, Moreira MAR, Queiroz GS, Esperidião MD, Santos DL. Drenagem pós-esvaziamento axilar por câncer de mama: procedimento indispensável? Femina. 2006;34(7):455-60.

7. Baroudi R, Ferreira CA. Seroma: how to avoid it and how to treat it. Aesthet Surg J. 1998;18(6):439-41. PMID: 19328174 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1090-820X(98)70073-1

8. Baroudi R, Ferreira CA. Contouring the hip and the abdomen. Clin Plast Surg. 1996;23(4):551-72.

9. Pollock H, Pollock T. Progressive tension sutures: a technique to reduce local complications in abdominoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;105(7):2583-6. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00006534-200006000-00047

10. Rios JL, Pollock T, Adams WP Jr. Progressive tension sutures to prevent seroma formation after latissimus dorsi harvest. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;112(7):1779-83. PMID: 14663220 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.PRS.0000090542.68560.69

11. Pollock T, Pollock H. Progressive tension sutures in abdominoplasty. Clin Plast Surg. 2004;31(4):583-9. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cps.2004.03.015

12. Nahas FX, Ferreira LM, Ghelfond C. Does quilting suture prevent seroma in abdominoplasty? Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;119(3):1060-4.

13. Rossetto LA, Garcia EB, Abla LF, Neto MS, Ferreira LM. Quilting suture in the donor site of the transverse rectus abdominis musculocutaneous flap in breast reconstruction. Ann Plast Surg. 2009;62(3):240-3. PMID: 19240517 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/SAP.0b013e318180c8e2

14. Meeske KA, Sullivan-Halley J, Smith AW, McTiernan A, Baumgartner KB, Harlan LC, et al. Risk factors for arm lymphedema following breast cancer diagnosis in Black women and White women. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;113(2):383-91. PMID: 18297429 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10549-008-9940-5

15. Di Martino M, Nahas FX, Barbosa MV, Montecinos Ayaviri NA, Kimura AK, Barella SM, et al. Seroma in lipoabdominoplasty and abdominoplasty: a comparative study using ultrasound. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;126(5):1742-51. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181efa6c5

16. Boggio RF, Almeida FR, Baroudi R. Pontos de adesão na cirurgia do contorno corporal. Rev Bras Cir Plast. 2011;26(1):121-6. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1983-51752011000100022

17. Kulber DA, Bacilious N, Peters ED, Gayle LB, Hoffman L. The use of fibrin sealant in the prevention of seromas. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997;99(3):842-9. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00006534-199703000-00034

18. Arantes HL, Rosique RG, Rosique MJF, Mélega JMA. Há necessidade de drenos para prevenir seroma em abdominoplastias com pontos de adesão? Rev Bras Cir Plast. 2009;24(4):521-4.

19. Bezerra FJF, Moura RMG. Utilização da "Técnica de Baroudi-Ferreira" no fechamento da área doadora do retalho do músculo latíssimo do dorso. Rev Soc Bras Cir Plast. 2007;22(2):103-6.

20. Stehbens WE. Postmastectomy serous drainage and seroma: probable pathogenesis and prevention. ANZ J Surg. 2003;73(11):877-80. PMID: 14616557 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1445-2197.2003.02832.x

21. Juçaba RC, Juçaba SF. Mastectomia radical modificada com drenagem por sucção à vácuo versus sem drenagem. Rev Bras Mastol. 2003;13(2):71-4.

22. Pogson CJ, Adwani A, Ebbs SR. Seroma following breast cancer surgery. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2003;29(9):711-7. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0748-7983(03)00096-9

23. Coveney EC, O'Dwyer PJ, Geraghty JG, O'Higgins NJ. Effect of closing dead space on seroma formation after mastectomy-a prospective randomized clinical trial. Eur J Surg Oncol. 1993;19(2):143-6.

24. Gerber LH, Hoffman K, Chaudhry U, Augustine E, Parks R, Bernard M, et al. Rehabilitation management: restoring fitness and return to functional activity. In: Harris JR, Lippman ME, Morrow M, Osborne CK, eds. Disease of the breast. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Linppicott Wilians & Wilkins; 2000. p.1001-7.

25. Camargo MC, Marx AG. Reabilitação física no câncer de mama. São Paulo: Roca; 2000.

26. Dawson I, Stam L, Heslinga JM, Kalsbeek HL. Effect of shoulder immobilization on wound seroma and shoulder dysfunction following modified radical mastectomy: a randomized prospective clinical trial. Br J Surg. 1989;76(3):311-2. PMID: 2655815 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/bjs.1800760329

27. Flew TJ. Wound drainage following radical mastectomy: the effect of restriction of shoulder movement. Br J Surg. 1979;66(5):302-5. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/bjs.1800660503

28. Silva MPP, Derchain SFM, Rezende L, Cabello C, Martinez EZ. Movimento do ombro após cirurgia por carcinoma invasor da mama: estudo randomizado prospectivo controlado de exercícios livre versus limitados a 90° no pós-operatório. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet. 2004;26(2):125-30. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0100-72032004000200007

29. Sugden EM, Rezvani M, Harrison JM, Hughes LK. Shoulder movement after the treatment of early stage breast cancer. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 1998;10(3):173-81. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0936-6555(98)80063-0

30. Nagel PH, Bruggink ED, Wobbes T, Strobbe LJ. Arm morbidity after complete axillary lymph node dissection for breast cancer. Acta Chir Belg. 2003;103(2):212-6. PMID: 12768866 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00015458.2003.11679409

31. Rietman JS, Dijkstra PU, Hoekstra HJ, Eisma WH, Szabo BG, Groothoff JW, et al. Late morbidity after treatment of breast cancer in relation to daily activities and quality of life: a systematic review. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2003;29(3):229-38. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1053/ejso.2002.1403

1. Sociedade Brasileira de Cirurgia Plástica, São Paulo, SP, Brazil

2. Hospital Daher Lago Sul, Brasília, DF, Brazil

3. Sociedade Brasileira de Anestesiologia, Brasília, DF, Brazil

Institution: Hospital Daher Lago Sul, Brasília, DF, Brazil.

Corresponding author:

Ismar Ribeiro Júnior

Av. Pau Brasil, Lote 20, Apt 2402-2, 20

Aguas Claras, DF, Brazil Zip Code 71926-000

E-mail: ismarjr@gmail.com

Article received: November 29, 2015.

Article accepted: April 10, 2016.

Conflicts of interest: none.

Read in Portuguese

Read in Portuguese

Read in English

Read in English

PDF PT

PDF PT

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to Cite

How to Cite

Mendeley

Mendeley

Pocket

Pocket

Twitter

Twitter