Original Article - Year 2024 - Volume 39 -

Non-melanoma skin cancer: A study on the epidemiological profile and flow at HC-UFMG

Câncer de pele não melanoma: Um estudo sobre o perfil epidemiológico e fluxo no HC-UFMG

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Keratinocyte, basal cell, and squamous cell carcinomas are the main types of

non-melanoma skin cancer (NMSC). Although they do not represent a high risk

of mortality, these neoplasms have a significant impact on public health,

causing aesthetic and functional damage, especially in areas constantly

exposed to the sun, such as the head, neck, and face. Surgery is an

established approach in the treatment of NMSC. The present study aims to

outline an epidemiological profile of patients undergoing surgery for the

treatment of NMSC by the plastic surgery service of the Hospital das

Clínicas of the Federal University of Minas Gerais (UFMG).

Method: A descriptive epidemiological study was carried out at the Borges da Costa

Outpatient Clinic of the Hospital das Clínicas of UFMG between March and

August 2023. A form was developed for data collection, covering variables

relevant to the epidemiological analysis.

Results: The sample of 26 patients had a mean age of 69 years, with a predominance of

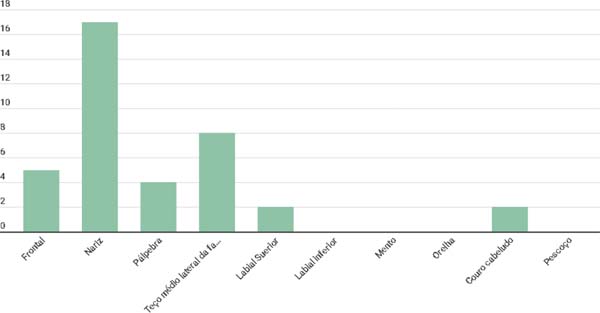

white patients (88.4%). The lesions were most frequent on the nose (53.8%),

lateral middle third of the face (20.5%), and forehead (12.8%). Regarding

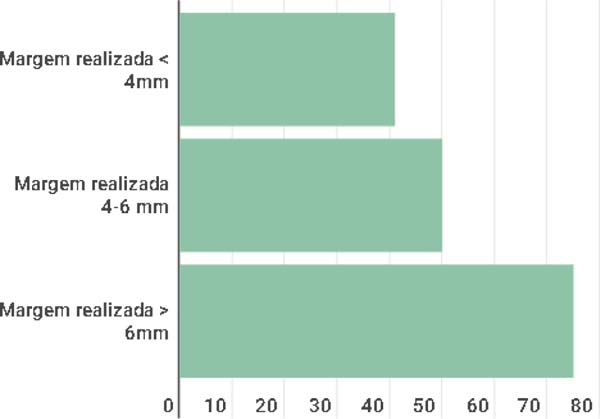

the margin, 55.8% had free margins, 41.1% had compromised margins, and 2.9%

had narrow margins.

Conclusion: The results highlight the need to systematize the care flow for patients with

NMSC, aiming at a more effective compilation and evaluation. In addition,

the epidemiological peculiarities of the patients treated could be

identified and evaluated through the proposed form, providing insights for

improvements in the care and management of non-melanoma skin cancer in the

hospital.

Keywords: Skin neoplasms, Carcinoma; basal cell; Plastic surgery procedures; Epidemiologic studies; Carcinoma; squamous cell

RESUMO

Introdução: Os carcinomas de queratinócitos, basocelular e espinocelular, são os principais tipos de câncer de pele não melanoma (CPNM). Embora não representem um alto risco de mortalidade, essas neoplasias têm um impacto significativo na saúde pública, causando prejuízos estéticos e funcionais, principalmente em áreas constantemente expostas ao sol, como a cabeça, pescoço e face. A cirurgia é uma abordagem estabelecida no tratamento do CPNM. O presente estudo tem como objetivo traçar um perfil epidemiológico dos pacientes submetidos à cirurgia para o tratamento de CPNM pelo serviço de cirurgia plástica do Hospital das Clínicas da Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais (UFMG).

Método: Realizou-se um estudo epidemiológico descritivo no Ambulatório Borges da Costa do Hospital das Clínicas da UFMG, entre março e agosto de 2023. Um formulário foi desenvolvido para a coleta de dados, abrangendo variáveis relevantes para a análise epidemiológica.

Resultados: A amostra de 26 pacientes apresentou uma média de idade de 69 anos, com predominância de pacientes brancos (88,4%). As lesões foram mais frequentes no nariz (53,8%), terço médio lateral da face (20,5%), e frontal (12,8%). Quanto à margem, 55,8% vieram com margens livres, 41,1% comprometidas e 2,9% com margens exíguas.

Conclusão: Os resultados destacam a necessidade de sistematização do fluxo assistencial para pacientes com CPNM, visando uma compilação e avaliação mais eficaz. Além disso, as peculiaridades epidemiológicas dos pacientes atendidos puderam ser identificadas e avaliadas através do formulário proposto, fornecendo insights para melhorias no atendimento e na gestão do câncer de pele não melanoma no hospital.

Palavras-chave: Neoplasias cutâneas; Carcinoma basocelular; Procedimentos de cirurgia plástica; Estudos epidemiológicos; Carcinoma de células escamosas.

INTRODUCTION

Of all malignant neoplasms diagnosed worldwide, non-melanoma skin cancer is the most common type in both sexes.1,2 It is not a serious tumor and has a low mortality rate, although it can cause deformities in the body.

According to the National Cancer Institute (INCA), in Brazil, the number of new cases of non-melanoma skin cancer expected for each year of the triennium 2023-2025 will be 101,920 in men and 118,570 in women, corresponding to an estimated risk of 96.44 new cases per 100,000 men and 107.21 new cases per 100,000 women. The state of Minas Gerais has an estimated rate of 112.74 cases per 100,000 men and 127.43 cases per 100,000 women. In 2020, there were 1,534 deaths from non-melanoma skin cancer in men; this value corresponds to a risk of 1.48/100,000 and 1,119 deaths in women, with a risk of 1.03/100,0003.

Despite their high prevalence, these tumors are rarely fatal, accounting for less than 0.1% of all cancer-related deaths. Squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) are biologically more aggressive, and neglected lesions can be fatal due to local extension or metastasis.4 On the other hand, basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is very rarely fatal. However, the impact of non-melanoma skin cancer on public health is high, and although it does not pose a major threat to life, it can cause significant aesthetic and functional damage to patients, as it most frequently appears on skin that is constantly exposed to the sun, in the head and neck region and especially on the face.5

They are more common in people with fair skin over the age of 40, with the exception of those who already have skin diseases. However, this age profile has been changing with the constant exposure of young people to the sun’s rays.3 Excessive and chronic exposure to the sun is the main risk factor for the development of non-melanoma skin cancers.

Other risk factors for all types of skin cancer include skin sensitivity to the sun (lighter-skinned people are more sensitive to ultraviolet radiation from the sun), immunosuppressive diseases, and occupational sun exposure. Immunocompromised patients (such as transplant recipients and patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, for example) are at greater risk of developing non-melanoma skin cancer because they have decreased carcinogenic control of the skin4.

The main types of non-melanoma skin cancer are keratinocyte carcinomas. Of these, approximately 75% are BCCs and 25% are SCCs. BCCs are clinically categorized as nodular, superficial, and infiltrative or sclerosing. Nodular BCCs are most common and present as raised, waxy papules or nodules with telangiectasias. Superficial BCCs are horizontally enlarging and appear thin, with erythematous plaques with variable scaling and telangiectasias. Sclerosing BCCs are ill-defined, indurated red or white plaques that may be slightly elevated or depressed and atrophic.5

The clinical presentation of SCC includes invasive SCC and SCC in situ (Bowen’s disease). Invasive SCC of the skin often presents as an erythematous, keratotic papule, plaque, or nodule occurring on a background of an actinic lesion. These lesions may show ulceration, and patients often describe a history of intermittent bleeding and a nonhealing wound. Actinic keratosis and Bowen’s disease (SCC in situ) are considered precursor lesions of SCC and often present as a well-demarcated erythematous, scaly plaque.6

The diagnosis of keratinocyte carcinomas predominantly involves clinical diagnosis, dermoscopy, and biopsy. Physicians familiar with the manifestations of BCC can often make a strong diagnostic hypothesis based on clinical examination alone. In this case, examination of the lesion with a dermatoscope can always assist in the clinical diagnosis of BCC7.

Although clinical and dermoscopic findings may strongly suggest the diagnosis, a histopathological examination is necessary to confirm the suspected diagnosis. This is also useful for evaluating perineural invasion, tumor differentiation, and tumor depth, which are important factors for tumor staging and prognosis. Thus, it can be said that histopathology is the gold standard for the diagnosis of non-melanoma skin cancer8.

Imaging is reserved for patients with clinically aggressive lesions to determine the extent of invasion or to help evaluate for distant metastases in the presence of clinical suspicion or clinically palpable adenopathy. It is important to recognize that SCC of the lip is considered an oral cancer and, therefore, requires careful clinical examination and may require radiographic evaluation of the lymphatic region.

The prognosis depends on the type of tumor and the treatment established. Risk factors associated with recurrence and metastasis include lesion size > 2 cm in diameter, location in the central part of the face or ears, long duration of the lesion, incomplete excision, aggressive histological type, or perineural or perivascular involvement9.

The following treatment options are available: curettage, electrocoagulation, conventional surgery, topical or intralesional agents, radiotherapy, Mohs micrographic surgery, cryotherapy, photodynamic therapy, and systemic therapies. The therapeutic approach depends on the stage, the clinicopathological pattern of the lesion, and the patient’s clinical conditions10.

According to the 2023 National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines11,12, conventional surgery is the first-line treatment for low-risk non-melanoma skin cancer (NMSC); in addition, radiation therapy is an important adjuvant therapy. For patients with high-risk BCCs and SCCs, first-line therapy consists of Mohs micrographic surgery and complete circumferential and deep margin excision (CCPDMA).

In the SUS, the main flow is based on the therapeutic options of conventional surgery and radiotherapy. In this sense, some therapeutic options useful in the treatment of NMSC, such as Mohs micrographic surgery and the CCPDMA excision technique, have little space in the SUS Network, mainly due to their high cost. Such options are extremely relevant for the treatment, mainly of high-risk NMSC, in addition to being able to be used with the objective of obtaining a better aesthetic result in numerous cases.

Therefore, with so many variations and aspects of treatment, a constant epidemiological evaluation of the types of NMSC and outcomes becomes of fundamental importance, as well as a systematization of the care of these patients in search of better therapeutic options and better outcomes.

OBJECTIVE

To develop an epidemiological profile of patients with NMSC who underwent surgery at the plastic surgery service of the Hospital das Clínicas of the Federal University of Minas Gerais (HC-UFMG) in Belo Horizonte.

METHOD

The research project consists of carrying out a descriptive epidemiological study of patients with suspected or diagnosed non-melanoma skin cancer undergoing surgical treatment at the Borges da Costa Outpatient Clinic of the Hospital das Clínicas of UFMG during the period from April 2023 to August 2023.

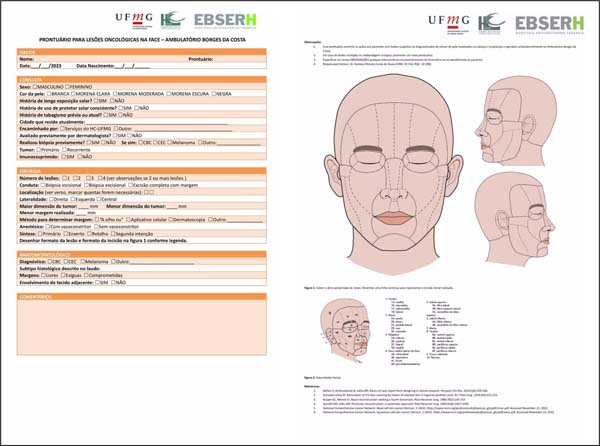

After a literature review, variables were considered for stratification and defining conduct in these patients, in addition to modifications made in order to adapt the practice of HC-UFMG. Among the variables, data such as date of birth, sex, sun exposure, immunosuppressed patient, topography of the lesion, surgical conduct adopted, margin performed, and margin compromise, among others, are included.

From this, a form model (Figure 1) was developed for data collection in the field, which was used to collect all variables contained in the epidemiological analysis.

The data were stored in the form of tables to relate the variables of interest. We then obtained the results necessary to perform prevalence calculations. These data were organized in the form of tables and subjected to statistical analysis.

This study has the following Certificate of Presentation of Ethical Appreciation (CAAE): 71468522.0.0000.5125. It was submitted on 06/23/2023.

RESULTS

In the analyzed group of 26 people, the average age of the patients treated was 69 years. In total, 9 (34.6%) were male and 17 (65.3%) were female. All were considered candidates for surgical treatment of a suspected or diagnosed NMSC lesion on the face. Of these, 88.4% were white, 3.8% were black, and 7% were light brown.

Regarding risk factors, it was identified that 88.4% of patients had a history of long-term sun exposure, but only 19.2% had a history of regular sunscreen use. In addition, 21.4% had a history of smoking, and 7.8% of patients were immunosuppressed. Among the patients included in the study, 100% were from Minas Gerais, 38.4% from Belo Horizonte, and 26.9% were patients referred from some service of HC-UFMG, with the remainder coming from external referrals.

Regarding the evaluation by a dermatologist prior to the plastic surgery consultation, it was identified that only 38.4% were evaluated by this specialist before arriving at the service. Furthermore, of the total number of patients analyzed, 38.4% had not had a previous biopsy. Of those who had a prior biopsy, 93.3% were BCC, and 6.6% were SCC.

Regarding the topographic distribution of lesions on the face, we identified that the main affected region was the nose (53.8%), followed by the middle lateral third of the face (20.5%) and forehead (12.8%) (Figure 2).

Regarding the type of lesion to be surgically treated, 69.4% were primary lesions, 25.0% were lesions with compromised margins, and 5.5% were recurrent lesions. In total, 39 lesions were resected, and an average of 1.5 lesions were surgically treated per patient. The approach involved complete excision with margins in 83.7% of patients, excisional biopsy in 13.5% of patients, and incisional biopsy in 2.7% of patients.

Among the methods used to determine the margin, 65.7% were “by eye,” and 34.2% were using a ruler. In 100% of the surgical approaches, an anesthetic with a vasoconstrictor was used. In 51.4% of the lesions, the synthesis was with a graft; in 31.4%, the synthesis was primary; and in 17.1%, the synthesis was with a flap. Regarding the surgical approach, 62.5% were the primary approach, and 37.5% were reapproaching. The largest dimension measured of the removed tumors was 20.4 mm, with the average margin being 3.70 mm.

Regarding the anatomopathological results of the reported lesions, 86.1% of the results showed BCC, 5.5% showed actinic keratosis, 5.5% showed SCC, and 2.7% showed unchanged skin. Regarding the margin, 55.8% had free margins, 41.1% had compromised margins, and 2.9% had narrow margins. Regarding lesion infiltration, 5.8% of the lesions were affecting the adjacent tissue.

DISCUSSION

Regarding the age group involved in the onset of non-melanoma skin cancer, according to INCA data from 2022, it occurs mainly from 40 years of age and in people with fair skin, which was compatible with the present study, which found that 88.4% of the patients identified had white skin and an average age of 69 years, with the youngest patient being 42 years old. This is mainly related to the long period of sun exposure due to photoaging and the occurrence of genetic mutations in skin cells13.

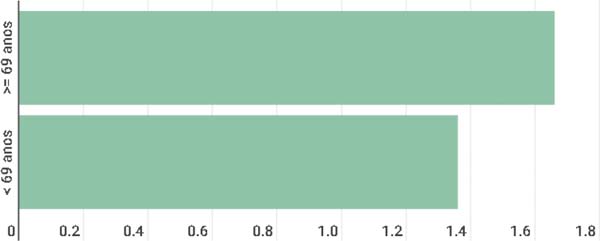

It was observed in the present study that age correlates with the incidence of multiple lesions since patients under 69 years of age tended to have a lower number of lesions (1.36 lesions/patient), and patients over 69 years of age tended to have a higher number (1.66 lesions/patient) (Figure 3).

Regarding the established flow, it was possible to observe in the present study that the average margin was 3.70 mm in patients treated at the Plastic Surgery Service of HC-UFMG. This data contrasts with the NCCN recommendation for BCC and SCC of a margin of at least 4 mm for low-risk NMSC11,12. Another point observed was that in approximately 65.7% of surgical approaches, the method of choice for defining the margins was “by eye” without the use of a precise numerical method for defining margins.

The guideline also states that flaps should not be used until the free margin has been established, with primary synthesis, synthesis by secondary intention, and grafts being acceptable in this case; however, it was shown that in the service in question, in 17.1% of the approaches, the flap had been used as a form of reconstruction of the lesion, and of these, only 40% came with free margins after the procedure.

The present study revealed that patients did not have a well-established risk stratification, which consequently led to them being treated in a generalized manner. Furthermore, the data collected for the research in question were poorly recorded in the institution’s medical records. These gaps in the service indicate the need for a well-established protocol for managing NMSC in the hospital.

It was identified that 5.5% of the lesions were recurrent, that is, the occurrence of a new lesion in the same topography as a lesion previously considered cured. Despite the low value, it is still a considerable number since there are surgical methods available that aim to reduce recurrence, such as Mohs micrographic surgery, when compared to conventional surgical excision, but it is known that this is still a method that is not widely available in the SUS14.

The anatomopathological results are in line with those recommended by the NCCN11,12 since a direct relationship was observed with the recommended minimum margin of 4-6 mm and the eventual outcomes in relation to margin compromise, as observed in Figure 4 which in lesions with margins smaller than 4 mm, 41.1% had free margins, in those with margins between 4-6 mm, 50.0% had free margins, and in lesions with margins > 6 mm, 75.0% of the results identified free margins.

CONCLUSION

This study allowed us to understand the epidemiological profile of patients treated and monitored by the Plastic Surgery Service at the Hospital das Clínicas of UFMG from March to August 2023. In order to propose measures to improve the flow of patients with NMSC in the hospital in question, the following stood out: the importance of systematizing the care flow for better compilation and evaluation of patients with NMSC within the institution and the epidemiological particularities of the patients treated at the service could be traced and evaluated with the application of the proposed form.

It is also concluded that the epidemiological model and surgical quality indicators found in this project can be used not only for the Borges da Costa Outpatient Clinic of the Hospital das Clínicas of UFMG but by other hospitals to direct efforts to improve hospital quality and morbidity of patients with NMSC.

These improvements include improved patient flow with a better recording of biopsy topography, better recording of the number of recurrences, and better recording of possible important variables for risk stratification of lesions that may interfere with the management and morbidity of these patients. Therefore, better organization of patient and lesion data is expected, data that are routinely lost in patients treated by multiple professionals without the use of an integrated protocol between dermatology, outpatient surgery and plastic surgery in the hospital.

REFERENCES

1. Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(6):394-424.

2. Ferlay J, Colombet M, Soerjomataram I, Dyba T, Randi G, Bettio M, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality patterns in Europe: Estimates for 40 countries and 25 major cancers in 2018. Eur J Cancer. 2018;103:356-87.

3. Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Instituto Nacional de Câncer (INCA). Incidência de Câncer no Brasil: Estimativa 2023. Rio de Janeiro; INCA; 2022 [Internet]. Disponível em: https://www.inca.gov.br/sites/ufu.sti.inca.local/files/media/document/estimativa-2023.pdf

4. Chapalain M, Baroudjian B, Dupont A, Lhote R, Lambert J, Bagot M, et al. Stage IV cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: treatment outcomes in a series of 42 patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34(6):1202-9.

5. Costa CS. Epidemiologia do câncer de pele no Brasil e evidências sobre sua prevenção. Diagn Tratamento. 2012;17(4):206-8.

6. Brandt MG, Moore CC. Nonmelanoma skin cancer. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2019;27(1):1-13.

7. Altamura D, Menzies SW, Argenziano G, Zalaudek I, Soyer HP, Sera F, et al. Dermatoscopy of basal cell carcinoma: morphologic variability of global and local features and accuracy of diagnosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62(1):67-75.

8. Madan V, Lear JT, Szeimies RM. Non-melanoma skin cancer. Lancet. 2010;375(9715):673-85.

9. Custódio G, Locks LH, Coan MF, Gonçalves CO, Trevisol DJ, Trevisol FS. Epidemiology of basal cell carcinomas in Tubarão, Santa Catarina (SC), Brazil between 1999 and 2008. An Bras Dermatol. 2010;85(6):819-26.

10. Laranjeira FF, Nunes AGP, Oliveira HM, Machado G, Moreira LF, Corleta OC. Fatores prognósticos de recidiva no carcinoma basocelular da face. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2019;34(Suppl.1):37-9.

11. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines ®) Squamous Cell Skin Cancer [Internet]. 2023. [cited 2023 Oct 14]. Available from: https://www.nccn.org

12. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines ®) Basal Cell Skin Cancer [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2023 Oct 14]. Available from: https://www.nccn.org

13. Machado Filho CDS, Andrade FL, Odo LM, Paschoal LHC, Gouveia NC, Kurita VJ. Neoplasias malignas cutâneas: estudo epidemiológico. Arq Med ABC. 2002;26(3):10-7.

14. Brito JAGSM, Lopes LS, Rodrigues ALG, Brito CVB. Utilização da cirurgia de Mohs no tratamento de neoplasias Malignas não melanocíticas da pele. Medicina (Ribeirão Preto). 2021;54(3):e-170517.

1. Hospital das Clínicas, Universidade Federal de

Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil

Nathan Joseph Silva Godinho Av. Prof. Alfredo Balena, 190 - Santa Efigênia, Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil., Zip Code: 30130-100, E-mail: nathanjoseph.sg@gmail.com

Artigo submetido: 05/02/2024.

Artigo aceito: 26/07/2024.

Conflicts of interest: none.

Read in Portuguese

Read in Portuguese

Read in English

Read in English

PDF PT

PDF PT

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to Cite

How to Cite

Mendeley

Mendeley

Pocket

Pocket

Twitter

Twitter