INTRODUCTION

Morel-Lavallée injury (LML) is a rare and potentially serious condition characterized

by an accumulation of fluid and necrotic tissue between the skin and underlying muscular

fascia caused by a shear force. Although it is an uncommon event, it is important

to recognize the signs and symptoms of the injury for early diagnosis and treatment.

The injury is often associated with high-energy trauma, such as car accidents, falls,

or sports injuries, and most commonly affects areas of bony prominence, such as the

thighs, hips, and lower back1. As it is an uncommon injury, there is little statistical data on its prevalence,

with an approximate ratio of 2:1 in men compared to women being stipulated, probably

due to the greater number of cases of polytrauma in men2, in addition to a prevalence of 8.3% of injury in the context of pelvic trauma3.

Accurate diagnosis of LML is crucial for adequate treatment and prevention of complications.

Diagnosis is typically made through physical examination, clinical history, and imaging

tests such as ultrasound (US) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). US can reveal

an anechoic image amidst a hyperechoic mass, while MRI can show a homogeneous hyperdense

lesion, located anterior to the muscular layer and posterior to the hypodermis. However,

it is important to emphasize that imaging findings are not specific and must be considered

together with the clinical history and physical examination for a correct diagnosis4.

OBJECTIVE

This article aims to report a successful case in the treatment of Morel-Lavallée lesion

in a secondary hospital, highlighting the surgical approach performed and the results

achieved.

CASE REPORT

A 36-year-old man with a history of falling from a motorcycle at high speed with an

exclusive injury to the right lower limb, presenting only abrasions on the right knee,

seeks care at the São Luiz Gonzaga Hospital, in São Paulo-SP, 3 days after the accident,

with the appearance of local edema, chills and phlogistic signs. Patient smoker, with

no other relevant history.

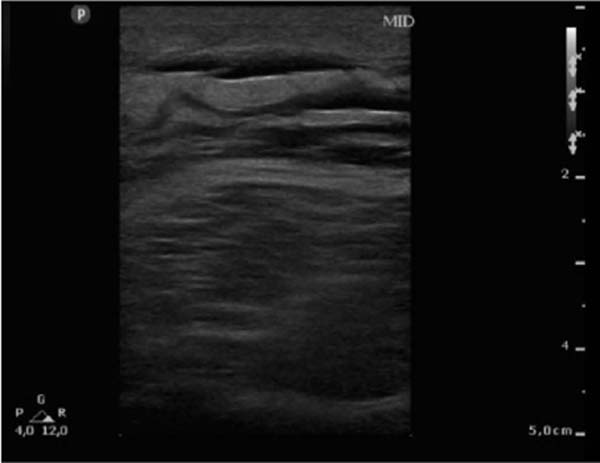

US of the right lower limb was performed, showing intact skin with thickened subcutaneous

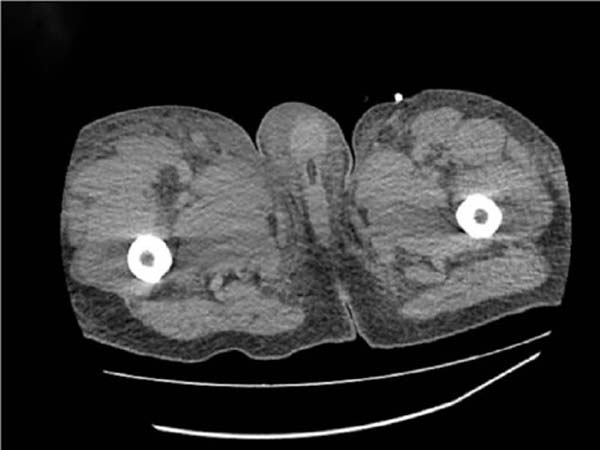

cellular tissue with a heterogeneous appearance throughout the right lower limb (Figure 1), in addition to a computed tomography (CT) showing the same changes (Figure 2).

Figure 1 - Ultrasonography of the right lower limb on the 4th day of hospitalization showing

thickened skin and subcutaneous adipose tissue, with a heterogeneous appearance and

with thin layers of liquid between them.

Figure 1 - Ultrasonography of the right lower limb on the 4th day of hospitalization showing

thickened skin and subcutaneous adipose tissue, with a heterogeneous appearance and

with thin layers of liquid between them.

Figure 2 - Computed tomography of the lower limbs on the 4th day of hospitalization showing diffuse

skin and subcutaneous edema without loss of continuity.

Figure 2 - Computed tomography of the lower limbs on the 4th day of hospitalization showing diffuse

skin and subcutaneous edema without loss of continuity.

Right at the beginning of hospitalization, the condition worsened, with fever, nausea,

increased edema, and tissue necrosis, requiring antibiotic therapy guided by blood

culture (piperacillin/tazobactam + oxacillin) associated with escharotomy and debridement

of the devitalized tissue in the surgical center after 4 days of hospitalization and

again after 19 days (Figure 3).

Figure 3 - Debridement of the lesion in the operating room.

Figure 3 - Debridement of the lesion in the operating room.

In the fourth week, debridement of the devitalized tissue was repeated in a surgical

center under spinal anesthesia, this time associating a vacuum dressing on the lesion

for 48 hours without success in stabilizing the local infectious condition. It was

decided to escalate antibiotic therapy to meropenem and polymyxin B for 13 days in

conjunction with simple daily washing and dressing changes associated with new debridement

of the devitalized and infected tissue weekly for two weeks.

In the sixth week, with control of the infectious condition, a suture was performed

with inversion of the edges, elastic suture on viable tissues in the thigh (Figure 4), and debridement on the other injured tissues (Figures 5 and 6), with the removal of the elastic suture after 7 days. Hemoglobin levels were maintained

above 10 g/dl throughout treatment, with transfusion support of 9 packed red blood

cells in total.

Figure 4 - Postoperative appearance of elastic suture.

Figure 4 - Postoperative appearance of elastic suture.

Figure 5 - Injury to the right leg.

Figure 5 - Injury to the right leg.

Figure 6 - Injury to the right thigh.

Figure 6 - Injury to the right thigh.

With success in reducing the wound’s bloody bed, a dressing change was scheduled every

3 days with silver sulfadiazine and new debridement in the surgical center weekly.

In the ninth week, a partial skin graft was performed on the ankle and dorsum of the

right foot with the donor area on the left thigh, followed by a partial skin graft

on the right thigh after another two weeks due to the lack of complete closure of

the lesion after the elastic suture due to size of the lesion (Figure 7).

Figure 7 - Partial skin graft on the right thigh.

Figure 7 - Partial skin graft on the right thigh.

During hospitalization, motor physiotherapy was performed on alternate days to maintain

the functionality of the lower limb. The patient presented complete resolution of

the condition after 3 months, with continued hospitalization for another month to

undergo physiotherapy for social reasons, being discharged after 4 months of hospitalization,

walking without assistance, with the graft integrated without dehiscence (Figure 8).

Figure 8 - 30 days postoperative of partial skin grafting on the right thigh and right leg.

Figure 8 - 30 days postoperative of partial skin grafting on the right thigh and right leg.

DISCUSSION

Treatment of LML is highly individualized, taking into account the extent of the lesion,

the presence of associated complications, and the patient’s response to initial therapy.

Therapeutic options can range from conservative approaches to more invasive interventions,

depending on the severity and evolution of the injury.

In less severe injuries, drainage of the accumulated fluid is often performed through

image-guided percutaneous aspiration or the use of closed drains, aiming to remove

the fluid and establish an environment conducive to healing. Surgical debridement

is a more invasive therapeutic option that may be indicated in cases of extensive

necrotic tissue, the presence of abscesses, or persistent infection. Complete removal

of devitalized and contaminated tissue is essential to promote adequate healing and

avoid subsequent infectious complications5, 6.

The case reported illustrates this therapeutic approach well. The patient suffered

the trauma, presenting only abrasions on the right knee initially, but developed local

edema, phlogistic signs, and fever after three days. Ultrasonography and computed

tomography confirmed the diagnosis of LML. The patient progressed to sepsis, requiring

targeted antibiotic therapy and multiple surgical debridements to remove the necrotic

tissue. During hospitalization, the complexity of management included the use of vacuum

dressings, changing antibiotics, and repeated debridement, demonstrating the importance

of an aggressive, individualized, and multimodal approach to complicated cases.

After surgical debridement, the use of vacuum dressings plays a key role in stabilizing

the lesion and progression to granulation tissue. These dressings help reduce seroma

formation, promote tissue adhesion, minimize the risk of secondary infection, and

promote healing by secondary intention7.

In more serious situations, where there is significant involvement of the underlying

muscle tissue, surgery may be necessary to remove the necrotic tissue and repair the

muscle injuries8. In these cases, tissue reconstruction can be performed using skin grafts, muscle

flaps, or primary closure techniques, depending on the extent of the injury and the

patient’s characteristics9, 10. These procedures aim to restore the structural and functional integrity of the affected

region, allowing adequate recovery of muscle function.

Our patient’s treatment included several of these strategies, culminating in skin

grafts and elastic suturing for functional recovery. Physiotherapy was essential for

rehabilitation, allowing the patient to regain full functionality of the affected

limb. The recovery process was prolonged, with hospital discharge after four months

of hospitalization, highlighting the need for multidisciplinary and prolonged management

to optimize clinical results.

CONCLUSION

The case presented highlights the crucial importance of rapid diagnosis and early

surgical management of Morel-Lavallée lesions. Promptness in identifying this type

of injury is essential to avoid serious complications and promote a more effective

recovery.

Surgical intervention with debridement of devitalized tissues in a surgical environment

emerges as a key element to limit the progression of the lesion, prevent secondary

infections, and promote healthy healing, with subsequent application of partial skin

grafts as necessary.

Furthermore, the multidisciplinary approach is a vital aspect of this process, evidenced

by close collaboration with a motor physiotherapy team. The integration of rehabilitation

strategies from the initial phases of treatment is essential to optimize motor function

and accelerate the patient’s recovery.

REFERENCES

1. Palacio EP, Stasi GGD, Lima EHRT, Mizobuchi RR, Durigam Júnior A, Galbiatti JA. Resultados

do tratamento cirúrgico da lesão de Morel-Lavallée. Rev Bras Ortop. 2015;50(2):148-52.

2. Dodwad SN, Niedermeier SR, Yu E, Ferguson TA, Klineberg EO, Khan SN. The Morel-Lavallée

lesion revisited: management in spinopelvic dissociation. Spine J. 2015;15(6):e45-51.

3. Nickerson TP Zielinski MD, Jenkins DH, Schiller HJ. The Mayo Clinic experience with

Morel-Lavallée lesions: establishment of a practice management guideline. J Trauma

Acute Care Surg. 2014;76(2):493-7.

4. van Gennip S, van Bokhoven SC, van den Eede E. Pain at the knee: the Morel-Lavallée

lesion, a case series. Clin J Sport Med. 2012;22(2):163-6. DOI: 10.1097/JSM.0b013e318246ee33

5. Singh R, Rymer B, Youssef B, Lim J. The Morel-Lavallée lesion and its management:

A review of the literature. J Orthop. 2018;15(4):917-21. DOI: 10.1016/j.jor.2018.08.032

6. Greenhill D, Haydel C, Rehman S. Management of the Morel-Lavallée Lesion. Orthop Clin

North Am. 2016;47(1):115-25. DOI: 10.1016/j.ocl.2015.08.012

7. Camargo PAB, Bertanha M, Moura R, Jaldin RG, Yoshida RA, Pimenta REF et al. Uso de

curativo a vácuo como terapia adjuvante na cicatrização de sítio cirúrgico infectado.

J Vasc Bras. 2016;15(4):312-6.

8. Nakajima T, Tada K, Nakada M, Matsuta M, Tsuchiya H. Two Cases of Morel-Lavallée Lesion

Which Resulted in a Wide Skin Necrosis from a Small Laceration. Case Rep Orthop. 2020;2020:5292937.

DOI: 10.1155/2020/5292937

9. Monte ALR. Tratamento das lesões por desenluvamento cutâneo traumático. Rev Bras Cir

Plást. 2012;27(3 Suppl.1):89.

10. Badjate DM, Jain D, Phansopkar P, Wadhokar OC. A Physical Therapy Rehabilitative Approach

in Improving Activities of Daily Living in a Patient With Morel-Lavallée Syndrome:

A Case Report. Cureus. 2022;14(9):e29523. DOI: 10.7759/cureus.29523

1. Santa Casa de Misericórdia de São Paulo, São Paulo, SIP Brazil

2. Hospital São Luiz Gonzaga, São Paulo, SP Brazil

Corresponding author: Bruno Losi Zacharias R. Dr. Cesário Mota Júnior, 112, Vila Buarque, São Paulo, SP, Brazil. Zip Code: 01221-010.

E-mail: bruno_zaka@hotmail.com