Original Article - Year 2024 - Volume 39 -

Adaptation of endoscopic frontoplasty for patients with alopecia

Adaptação da frontoplastia endoscópica para pacientes com alopecia

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Aging of the upper third of the face is characterized primarily by eyebrow

ptosis, glabellar wrinkles, and deep transverse wrinkles. Endoscopic

frontoplasty is our treatment option of choice, but in cases of alopecia,

visible scars are not always acceptable to patients. We developed a

videoendoscopic approach with three incisions, two 3-cm temporal incisions,

and one 1-cm midline (sagittal) incision. This study aims to describe

subperiosteal frontoplasty through three incisions in patients with

frontotemporal alopecia, evaluating its applicability and efficacy.

Method: Twelve patients with alopecia, 10 males and two females, who underwent

frontoplasty through three incisions (two temporal incisions and one midline

incision), aged between 50 and 66 years, over 5 years, were retrospectively

evaluated.

Results: There were three complications: one case of insufficient correction of the

lateral portion of the eyebrow and two cases of recurrence of glabellar

wrinkles.

Conclusion: The endoscopic subperiosteal frontoplasty technique with only three incisions

proved to be a good alternative in the treatment of aging of the upper third

of the face in patients with alopecia, being effective, providing good

aesthetic results and low morbidity.

Keywords: Alopecia; Endoscopy; Esthetics; Face; Plastic surgery procedures

RESUMO

Introdução: O envelhecimento do terço superior da face se caracteriza basicamente pela ptose da sobrancelha, rugas glabelares e rugas transversais profundas. A frontoplastia endoscópica é a nossa escolha como opção de tratamento, porém, nos casos de alopecia, as cicatrizes aparentes nem sempre são aceitas por parte dos pacientes. Desenvolvemos a abordagem videoendoscópica com três incisões, sendo duas incisões temporais de 3cm e uma incisão na linha mediana (sagital) de 1cm. O objetivo deste estudo é descrever a frontoplastia subperiostal através de três incisões em pacientes com alopecia frontotemporal, avaliando sua aplicabilidade e eficácia.

Método: Foram avaliados retrospectivamente 12 pacientes com alopecia, sendo 10 do sexo masculino e dois do sexo feminino, submetidos a frontoplastia através de três incisões (duas incisões temporais e uma incisão na linha mediana), idade variando entre 50 e 66 anos, num período de 5 anos.

Resultados: As complicações foram três, sendo um caso de correção insuficiente da porção lateral da sobrancelha e dois casos de recidiva de rugas glabelares.

Conclusão: A técnica de frontoplastia endoscópica subperiostal com somente três incisões mostrou ser uma boa alternativa no tratamento do envelhecimento do terço superior da face em pacientes com alopecia, sendo efetiva, proporcionando bons resultados estéticos e baixa morbidade.

Palavras-chave: Alopecia; Endoscopia; Estética; Face; Procedimentos de cirurgia plástica.

INTRODUCTION

Facial aging is a gradual, complex, and multifactorial process. It is the result of changes in the quality, volume, and positioning of tissues.1-3 For educational purposes, the face is divided into three thirds or parts: upper third (frontal region), middle third (malar region and cheeks), and lower third (mandibular region).4 Plastic surgeons must have extensive technical and anatomical knowledge and aesthetic sensitivity to offer treatment options that address the face as a whole and can then work on all three parts of the face, addressing patients’ anxieties, expectations, and complaints.

Eyebrow ptosis, glabellar wrinkles, and deep, transverse wrinkles in the frontal region basically characterize aging of the upper third of the face.5 Surgical treatment of aging in this area can be performed using the classic open coronal frontoplasty (OCF) technique, limited incision temporal frontoplasty (TF), endoscopic frontoplasty (EF), and Gliding Brown Lifting (GBL)5-7.

Usually, in our daily practice, in a private clinic, we use EF to treat the frontal region, as described in a previous publication8, using five incisions in the scalp, one of them in the midline (sagittal), two in the sagittal (one on each side) with an extension of 1 cm, and two temporal incisions of 3 cm (these being coronal and lateral to the temporal fusion line - TL).

However, the technique described above is limited in its indication for patients with frontotemporal androgenic alopecia (AGA) and/or long foreheads, as it causes visible scars that patients do not always accept. Therefore, we developed the treatment of the frontotemporal region through videoendoscopy with three incisions: two 3 cm temporal incisions and a 1 cm midline (sagittal) incision.

OBJECTIVE

This study aims to describe the subperiosteal EF technique through three incisions (two temporal incisions and one midline incision) in patients with frontotemporal alopecia, evaluating its applicability and efficacy.

METHOD

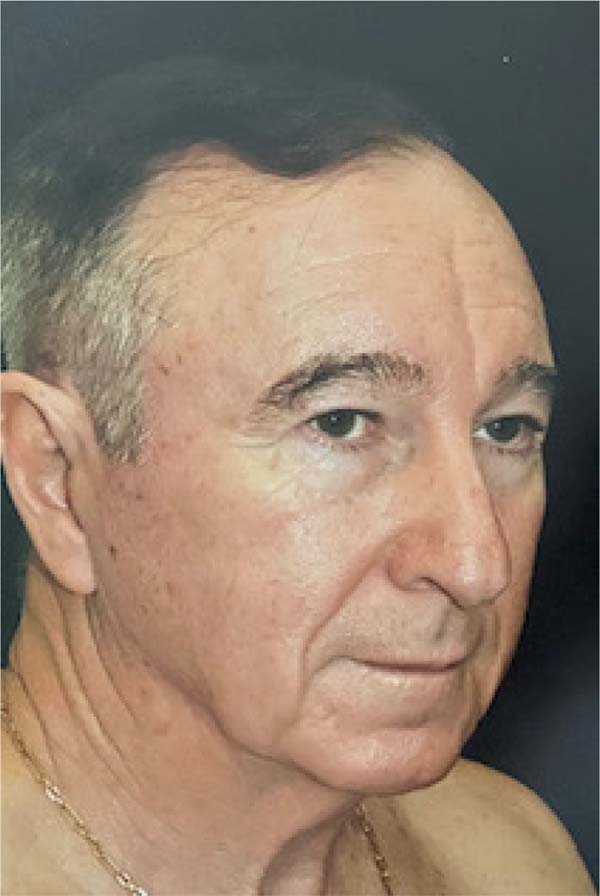

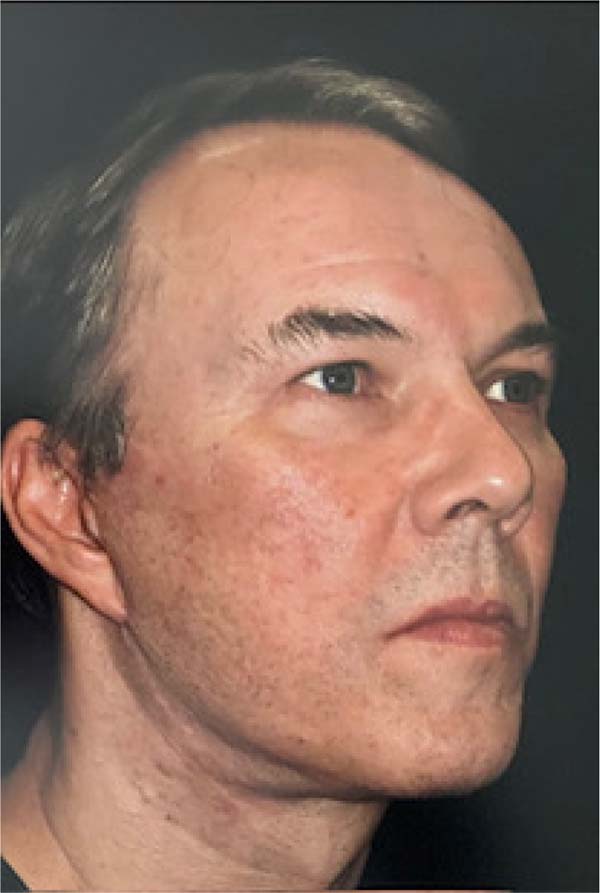

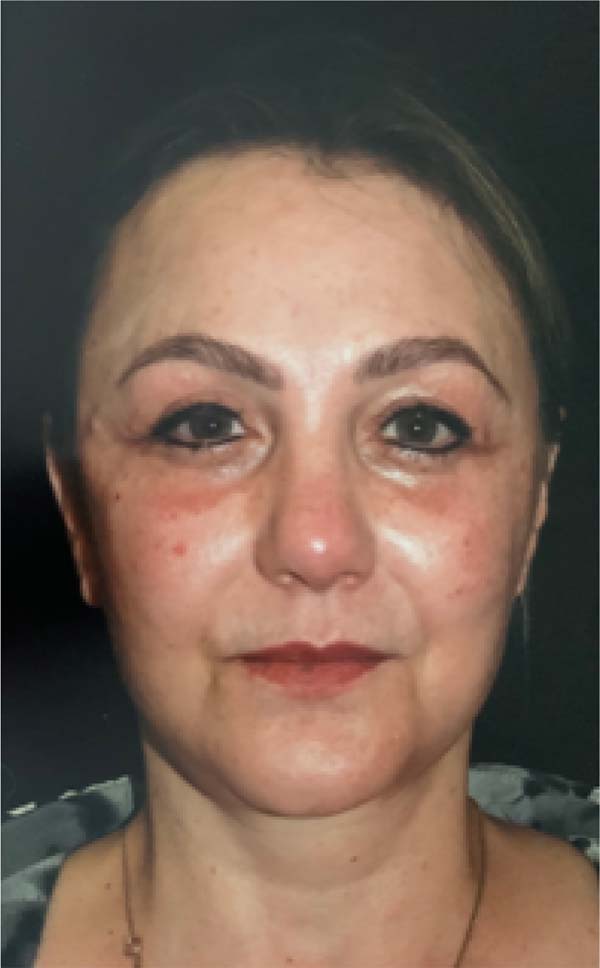

Twelve patients, 10 males and two females, who underwent EF through three incisions (two temporal incisions and one midline incision) in patients with frontotemporal alopecia, aged between 50 and 66 years, over 5 years, were retrospectively evaluated. The study was carried out in a private clinic in Curitiba, PR, between January 2019 and January 2023, approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Faculdade Evangélica Mackenzie do Paraná, number 6,500,820. Patients with previous frontoplasty surgery were excluded from the study.

Operating Technique

The patient was in the supine position and received 1g of intravenous cefazolin under local anesthesia (lidocaine 2% 20ml + ropivacaine 1% 20ml + 160ml of saline solution + adrenaline 1:1000 IU) and sedation. The entire frontal region was infiltrated up to the eyebrows, glabellar region, and temporal fossa, extending to the zygomatic arch and prominence of the malar bone.

Three incisions were made in the scalp, one of them in the midline (sagittal) and two 3 cm temporal incisions (these being coronal and lateral to the temporal fusion line - TL) (Figure 1).

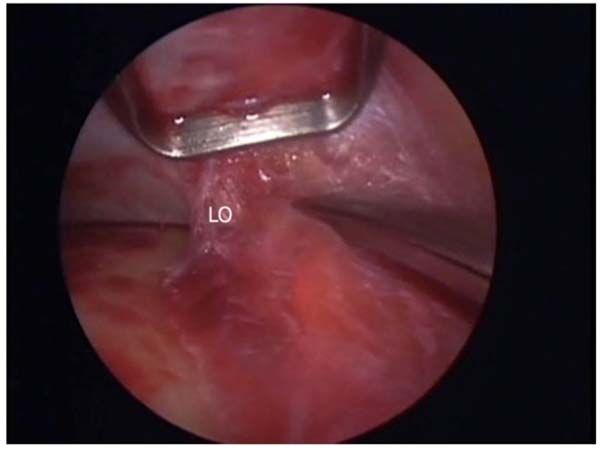

The dissection is subperiosteal with an inferior direction in the frontal region up to 2 cm above the orbital rim and laterally up to the TL; here, the periosteum is opened to gain access to the overlying anatomical structures. Laterally, in the temporal region, the dissection is performed below the posterior layer of the superficial temporal fascia and above the deep temporal fascia. The direction is also inferior until reaching the sentinel vein, the orbital ligament, the zygomatic temporal nerve (lateral and medial - sensitive), and the lateral canthal ligament (here, already in the supraperiosteal plane) (Figure 2).

The orbital ligament should be sectioned and released, with long Metzembaum scissors, as well as the entire TL, from lateral to medial until the two dissection planes communicate, the lateral (in the temporal region and below the superficial temporal fascia) and the central in the frontal region (subperiosteal). A Once the periosteum has been incised, the supraorbital and supratrochlear nerves are dissected and preserved, the muscles of the glabellar region are approached, and partial myectomy of the corrugator, depressor superciliaris, and procerus muscles is performed. Long-curved Kelly forceps are used here.

The flap is fixed in the temporal region by fixing the flap to the deep temporal fascia, as described by Knize5, using a 3.0 plastic Vycril thread with three stitches (Figure 3). The excess skin (redundant skin) of the flap that was pulled superoposteriorly is “accommodated” after its compensation; then, simple 4.0 nylon stitches are used to synthesize the scalp, and a micropore dressing is applied to the entire area of skin that was dissected.

RESULTS

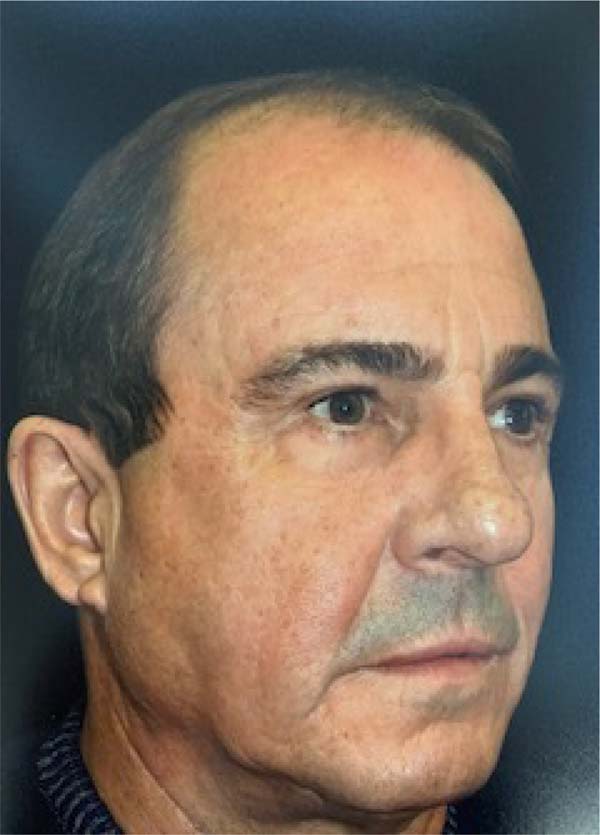

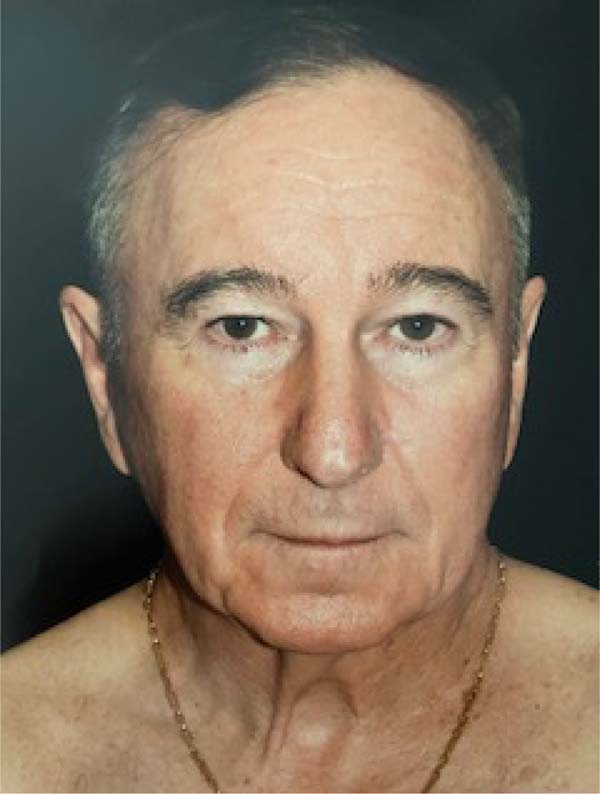

Twelve patients underwent surgery, 10 males and two females, with ages ranging from 50 to 66 years (Figures 4 to 19). There were three complications: one case of insufficient correction of the lateral portion of the eyebrow and two cases of recurrence of glabellar wrinkles (insufficient removal of muscles from the glabellar region). The complications occurred separately and not in association with a single patient.

DISCUSSION

Historically, most patients seeking cosmetic surgeries and procedures are women, but both lay, and scientific publications have highlighted the greater interest of men in this area. The reasons are many, but among them are the greater number of formerly obese patients - who have undergone bariatric surgery - and the search for improved self-esteem and quality of life, overcoming prejudices, and bringing more confidence9. North American studies show a 55% increase in the number of cosmetic surgeries in men between 1997 and 20189.

In the broader context of plastic surgery stakeholders, patients desire an improved appearance, as 79% of facial plastic surgeons reported in 2021, compared to 16% reported in 202010. Traditionally, the surgeries most sought after by men are gynecomastia, rhinoplasty, and hair transplant; currently, there is also interest in liposuction and facial surgery, and here, in particular, the demand for blepharoplasty associated with frontoplasty stands out9.

Eyebrow ptosis, glabellar wrinkles, and deep, transverse wrinkles in the frontal region basically characterize aging of the upper third of the face5. In our daily practice, in a private clinic, we use EF to treat the frontal region and adapt the concepts of Knize6,7, who carried out anatomical studies on the temporal fascia and the positioning of the branches of the supraorbital nerve.

From then on, Knize6,7 proposed the temporal frontoplasty technique with limited incisions associated with the treatment of glabellar wrinkles through the upper blepharoplasty incision. This technique has the advantage of avoiding the section of the supraorbital nerve branches. The EF, in turn, allows wide dissection of the flap, maximization of the image with easy identification of noble anatomical structures, such as nerves and muscles, allows good repositioning of the eyebrow, avoids hypoesthesia of the scalp and has a lower chance of alopecia8.

It is estimated that 80% of men and 50% of women may develop AGA during their lifetime. AGA is characterized by a reduction in hair thickness, length, and pigmentation; in women, it is more common in the pre-menopausal phase but with maintenance of the previous hairline (Ludwig pattern). In men, alopecia tends to be bicoronal with a vertex pattern, exposing the frontotemporal transition11.

Taking these characteristics into account, we thought of adapting the EF to avoid median scars (usually two) that should be positioned in the alopecia region and that tend not to be well accepted by patients. The use of the five classic incisions in the scalp8 was left aside in order to avoid visible scars. We, therefore, opted for only three access routes: one in the median line (sagittal - where the camera with the light source is placed) and two 3 cm temporal incisions (these are coronal and lateral to the TL).

It is very important to emphasize that it is through the median scars that the glabellar region is accessed, and with the use of forceps and specific material, the hypertrophic muscles that form the wrinkles in this region are treated.8 From the moment in which these access routes are not available, only the two temporal incisions remain, which are distant from the lower frontal region and which, also due to the convex shape of the frontal bone, have great technical difficulty in performing the partial myectomy of the corrugator and procerus muscles.

The subperiosteal dissection plane used in this study, which was proposed in the 1990s by Isse & Ramirez8, presents less bleeding and is below the plane through which the supratrochlear and supraorbital nerve branches pass. In other words, it is safer and has lower morbidity8. The flap is fixed with sutures in the temporal region, whose function is to stabilize the flap until it heals and adheres and not to pull it excessively upwards because fixation under tension causes recurrence. Therefore, it is worth emphasizing the need for wide dissection of the TL, in addition to all release of the periosteum along its adhesion areas (described by Mendelson)12.

Regarding complications, they were low in number, and there were no serious cases, such as injury to the temporal branch of the facial nerve, similar to data in the literature and also corroborated in our previous study8. This technique, although it allows good visualization of the anatomical structures of the glabella, does not allow effective treatment of the muscles of the glabellar region. However, it can be a good surgical alternative in patients with AGA, with complaints of aging of the upper third of the face, and who present ptosis of the tail of the eyebrow and less intense glabellar wrinkles.

The limitation of this study is the lack of comparison of the results with other frontotemporoplasty techniques under direct vision and without the use of a video endoscope, as described by Knize5,6 and Jacono1,8. And also the small sample size, although proportional to other studies in the area8.

CONCLUSION

The endoscopic subperiosteal frontoplasty technique with only three incisions has shown to be a good alternative in the treatment of aging of the upper third of the face in patients with alopecia, being effective, providing good aesthetic results and low morbidity.

REFERENCES

1. Jacono AA. A Novel Volumizing Extended Deep-Plane Facelift: Using Composite Flap Shifts to Volumize the Midface and Jawline. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2020;28(3):331-68.

2. Warren R, Gartstein V, Kligman AM, Montagna W, Allendorf RA, Ridder GM. Age, sunlight, and facial skin: a histologic and quantitative study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25(5 Pt 1):751-60.

3. Shaw RB Jr, Kahn DM. Aging of the midface bony elements: a three-dimensional computed tomographic study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;119(2):675-81; discussion: 682-3.

4. Coleman SR, Grover R. The anatomy of the aging face: volume loss and changes in 3-dimensional topography. Aesthet Surg J. 2006;26(1S):S4-9.

5. Knize DM. Limited-incision forehead lift for eyebrow elevation to enhance upper blepharoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1996;97(7):1334-42.

6. Knize DM. Limited incision foreheadplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999;103(1):271-84.

7. Viterbo F, Auersvald A, O’Daniel TG. Gliding Brow Lift (GBL): A New Concept. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2019;43(6):1536-46.

8. Graça L, Araújo LR, Graça ACM. Frontoplastia Endoscópica Subperiostal com Fixação Temporal por Fios de Sutura. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2022;37(1):3-8.

9. Lem M, Pham JT, Kim JK, Tang CJ. Changing Aesthetic Surgery Interest in Men: An 18-Year Analysis. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2023;47(5):2136-41.

10. American Academy of Facial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. AAFPRS Announces Annual Survey Results: Demand for Facial Plastic Surgery Skyrockets as Pandemic Drags On. Self-Improvement Surge Spills into Aesthetics in a Big Way with 40 Percent Increase in Facial Plastic Surgery in 2021 [Accessed 2022 Jul 2]. Available from: https://www.aafprs.org/Media/Press_Releases/2021%20Survey%20Results.aspx

11. Piraccini BM, Alessandrini A. Androgenetic alopecia. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2014;149(1):15-24.

12. Mendelson B, Wong CH. Changes in the facial skeleton with aging: implications and clinical applications in facial rejuvenation. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2012;36(4):753-60.

1. Clínica Privada, Cirurgia Plástica, Curitiba,

PR, Brazil

2. Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Paraná,

Escola de Medicina, Curitiba, PR, Brazil

3. Faculdade Evangélica de Medicina Mackenzie do

Paraná, Comitê de Ética em Pesquisa, Curitiba, PR, Brazil

Lincoln Graça Neto Rua Angelo Sampaio, 2029, Curitiba, PR, Brazil. Zip Code: 80420-160, E-mail: lgracaneto@hotmail.com

Artigo submetido: 22/11/2023.

Artigo aceito: 27/07/2024.

Conflicts of interest: none.

Read in Portuguese

Read in Portuguese

Read in English

Read in English

PDF PT

PDF PT

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to Cite

How to Cite

Mendeley

Mendeley

Pocket

Pocket

Twitter

Twitter