Original Article - Year 2024 - Volume 39 -

Impact of plastic surgery on body composition after bariatric surgery

Impacto da cirurgia plástica na composição corporal pós-cirurgia bariátrica

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Obesity is characterized by excess weight resulting from the accumulation of body fat, characterized by a body mass index (BMI) equal to or above 30 kg/m2. Currently, bariatric surgery is considered the most effective method for controlling class III obesity (BMI>40 kg/m2) associated or not with comorbidities and for class II obesity (BMI>35 kg/m2) with comorbidities.

Method: This is an uncontrolled prospective cohort study and 30 patients will be required, with the primary outcome being the difference between the percentage of body fat before and after abdominal dermolipectomy in patients after bariatric surgery.

Results: 30 patients were included in the study, of which 24 completed postoperative control exams. When comparing the average percentage of total body fat, total, visceral, and peripheral fat, there was no statistically significant difference. Weight had a significant drop (p=0.024) and, as expected, there was also a statistically significant decrease in BMI (p=0.017).

Conclusion: Patients benefit due to weight loss, improvement in comorbidities, and increased self-esteem. However, many patients have the disadvantage of having extensive sagging skin and this has a major impact on their physical and emotional quality of life. We assessed the need for knowledge of body fat before and after post-bariatric plastic surgery, to improve previous results and provide the patient with possibilities to optimize the prevention of future diseases.

Keywords: Obesity; Overweight; Weight loss; Body contouring; Body mass index; Electric impedance; Bariatric surgery.

RESUMO

Introdução: A obesidade é caracterizada pelo excesso de peso proveniente do acúmulo de gordura corporal, caracterizada por um índice de massa corporal (IMC) igual ou acima de 30 kg/m2. Atualmente, a cirurgia bariátrica é considerada o método mais eficaz para o controle da obesidade classe III (IMC>40 kg/m2) associado ou não a comorbidades e para obesidade classe II (IMC>35 kg/m2) com comorbidades.

Método: Trata-se de um estudo de coorte prospectivo não controlado e serão necessários 30 pacientes, tendo como desfecho primário a diferença entre percentual de gordura corporal pré e pós-dermolipectomia abdominal nos pacientes pós-cirurgia bariátrica.

Resultados: Foram incluídos 30 pacientes para o estudo, das quais, 24 completaram os exames de controle pós-operatório. Quando comparadas as médias de percentual de gordura corporal total, gordura total, visceral e periférica, não houve diferença estatisticamente significativa. Já o peso teve uma queda significativa (p=0,024) e, como esperado, também houve diminuição estatisticamente significativa do IMC (p=0,017).

Conclusão: Os pacientes se beneficiam devido à perda de peso, melhora de comorbidades e autoestima elevada. Porém, muitos pacientes apresentam a desvantagem de ficar com extensa flacidez de pele e isso impacta muito na qualidade de vida física e emocional. Avaliamos a necessidade de conhecimento da gordura corporal pré e pós-cirurgia plástica pós-bariátrica, a fim de melhorar resultados prévios e proporcionar ao paciente possibilidades de otimizar a prevenção de doenças futuras.

Palavras-chave: Obesidade; Sobrepeso; Redução de peso; Contorno corporal; Índice de massa corporal; Impedância elétrica; Cirurgia bariátrica.

INTRODUCTION

Obesity is characterized by excess weight resulting from the accumulation of body fat, characterized by a body mass index (BMI) equal to or above 30 kg/m2. In Brazil, at the turn of 2002 to 2003, four in ten Brazilians were overweight. The latest information is that now there are six out of every ten Brazilians. In other words, around 96 million people are overweight in the country — that is, the result of their BMI indicates that they are in the overweight or obese range. If we focus exclusively on the percentage of adults with obesity, we will see that it more than doubled in the same period, going from 12.2% to 26.8%. There is no doubt: it is urgent to do something1.

The prevalence of overweight and obesity continues to increase around the world, and developed countries face a progressive increase in the number of people who are severely obese (defined as a body mass index of 40kg/m2)2. The body mass index used to define overweight, obesity and morbid obesity is 25.0 to 29.9, 30.0 to 39.9, and above 40 kg/m2, respectively3.

The prevalence of extreme or grade 3 obesity (BMI>40 kg/m2) has increased threefold in the US over the past four decades, and 3% of adults are classified as extremely obese. Recent reports also confirm an increase in prevalence rates in this population. One consequence of this demographic change is that it is now necessary to assess the body composition of extremely obese individuals, both in clinical practice and as part of research, to assess the effectiveness of different treatment programs4.

Body composition and bioimpedance

Some physiological concepts are necessary for general understanding: total body water is the sum of intracellular and extracellular fluid. Total cell mass corresponds to intracellular water and visceral proteins. Fat-free mass corresponds to visceral proteins, total body water, and bone mineral. Therefore, what remains of this equation is body fat5.

Severe obesity is characterized by large changes in body compartments compared to overweight or non-obese people. In addition to increased adipose tissue mass, a general increase in total body hydration, and in particular an expansion of extracellular water volume (ECW) relative to intracellular water volume (ICW), generally accompanies this physiological state6. Bioimpedance analysis (BIA) is easy, non-invasive, relatively inexpensive, and can be performed on virtually any individual as it is portable. Data suggest that BIA works well in healthy individuals and patients with stable water and electrolyte balance with a validated equation that is age, sex, and race appropriate7.

Inbody Segmental Tetrapolar bioimpedance analysis allows the determination of fat-free mass (FFM), fat mass (FM), and total body water (TCA) in individuals without significant changes in fluids and electrolytes, when using appropriate population equations, age, or pathology and established procedures. According to the Brazilian Medical Association, segmental multifrequency bioimpedancemetry equipment that uses 8 electrodes is the most suitable for assessing body composition and can be considered the most accurate8.

Treatment

Currently, bariatric surgery is considered the most effective method for controlling class III obesity (BMI>40kg/m2) associated or not with comorbidities and for class II obesity (BMI>35kg/m2) associated with comorbidities. Monitoring body composition is very important for individuals undergoing bariatric surgery, as the ideal loss of body mass should be associated with a decrease in body fat mass and the maintenance of body fat-free mass in the short and long term after surgery3.

Ideally, weight loss should occur primarily due to the reduction in fat mass (FM), minimizing the loss of fat-free mass (FFM). The assessment of body composition plays an important role in the clinical assessment and monitoring of changes in FM and FFM during specific therapeutic regimens in obese individuals, as a way of determining the effectiveness of interventions concerning weight loss9.

Post-operative follow-up and plastic surgery

The greatest loss of fat mass occurs in the first 2 years of bariatric surgery. Patients benefit due to weight loss, improvement in comorbidities, and increased self-esteem. However, many patients have the disadvantage of having extensive sagging skin and this has a major impact on their physical and emotional quality of life. To correct this condition, there are several procedures that we call body contouring surgery, such as dermolipectomy to correct an apron abdomen, mammoplasty for sagging breasts; cruroplasty and brachioplasty to correct excess skin on the thighs and arms, respectively10.

In the literature, some questionnaires measure the functional effectiveness of plastic surgery. The BODY-Q proved to be an objective and safe measure to assess the quality of life of patients after post-bariatric surgery11. Other studies have proven the improvement in patients’ quality of life after post-bariatric surgery12.

Patients who underwent body contouring surgery after RYGB surgery maintained a significantly lower average weight up to 7 years of follow-up than those who did not have surgery13. Patients undergoing body-contouring surgery after laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding have significant improvement in long-term BMI control10. Another study showed that body contouring surgery can help these patients maintain weight loss, in addition to the proven benefits in quality of life and functionality14, 15.

OBJECTIVE

To analyze total body composition before and after plastic surgery in patients undergoing bariatric surgery, in addition to comparing the percentage of total body fat before and after plastic surgery in patients undergoing bariatric surgery.

Check body fat-free mass and visceral fat before and after plastic surgery after bariatric surgery.

METHOD

The work is an uncontrolled prospective cohort study.

Data collection was carried out at the Obesity and Metabolic Syndrome Surgery Service of the São Lucas Hospital of the Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio Grande do Sul (HSL/PUCRS), room 801.

Only women were chosen, as the majority of patients undergoing bariatric surgery are female.

The patients had their body composition assessed by segmental Tetrapolar Bioimpedance InBody 770 at the Bariatric and Metabolic Surgery and Plastic Surgery Clinic of the PUCRS Clinical Center (COM-PUCRS) before plastic surgery and 90 days after the procedure. The exams will be paid for by the COM-PUCRS service.

The procedure performed was dermolipectomy to correct the apron abdomen. The volume of the liposuction (if associated with the procedure), the absolute weight in grams of the tissue removed, which will be transformed into volume to add to the liposuctioned fat, and its percentage concerning the patient’s weight was measured.

Sample size

The body fat percentage (BFP) of a normal female person is 18 to 28%. The average of pre-plastic surgery patients is 34%, in a range of 29 to 40, which gives a standard deviation of 3.5. For an α=5% and a statistical power of 90%, 30 patients are needed to evaluate the minimum clinically relevant difference of 2.2 percentage points of BFP.

Inclusion criteria

As inclusion criteria, the following were defined: Women (18 to 60 years old), abdominal dermolipectomy as surgery performed, post-bariatric surgery patients who underwent treatment with Sleeve or gastric bypass, participation permitted by the attending physician, having read and agreed to participate voluntarily and have signed the Free and Informed Consent Form.

Exclusion criteria

Patients with the use of medications that alter body physiology, severe and decompensated psychiatric illness, and altered preoperative exams (blood count, TP/KTTP fasting blood glucose, and creatinine) were excluded from the study.

Data analysis

The data were entered into the Excel program and later exported to the IBM SPSS statistics version 20.0 program for statistical analysis. The normality of the variables was checked using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Quantitative variables were described by mean and standard deviation and compared using Student’s t-test for paired samples. The mean difference and its 95% confidence interval were presented. To evaluate the correlation between measurements, Pearson’s correlation coefficient was used, and simple linear regression was used to evaluate the variation in visceral fat according to variations in peripheral fat and percentage of total body fat. A significance level of 5% was considered for the comparisons established.

Scientific and ethical approvals

This project will be sent to the HSL Research Committee (CPC) and the Scientific Committee of the PUCRS School of Medicine (ESMED). It was then submitted and approved on Plataforma Brasil by the PUCRS Research Ethics Committee. It should be noted that the study is following Resolution No. 466/2012 of the National Health Council, which provides for Ethics in Research with Human Beings and Terms of Commitment in the Use of Data (TCUD).

It should be noted that the TCUD foresees the possibility of sharing data in the future to build an interinstitutional database that allows new analyses that increase the robustness of research by expanding the sample size. Furthermore, it includes the use of data by the main researchers for analysis with Artificial Intelligence for relevant detections on the topic and the development of new technologies.

RESULTS

Thirty patients were included, of which 6 did not undergo postoperative bioimpedance analysis, therefore, it was not possible to compare them with the preoperative period. Data were collected from 24 female participants, with a mean age of 43.5 years (standard deviation of 10.2 years). The average weight of the piece was 1696 grams (standard deviation of 929 grams).

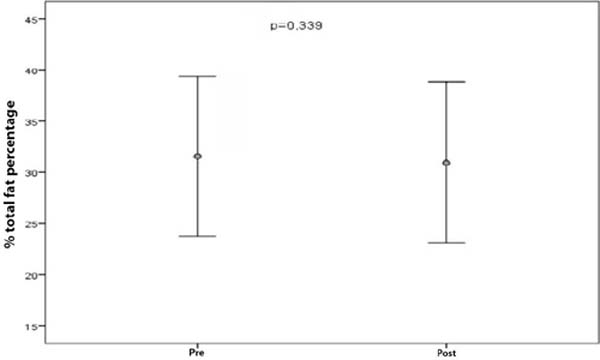

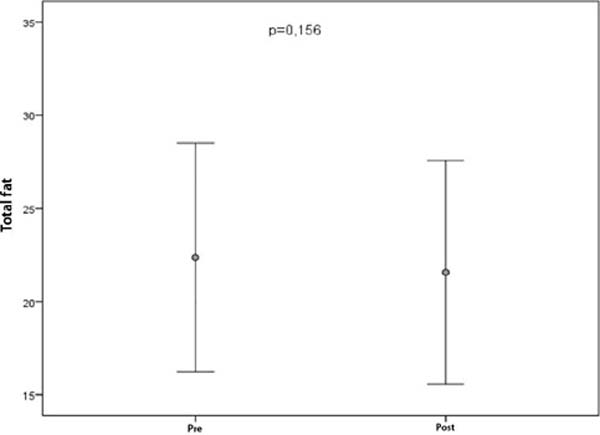

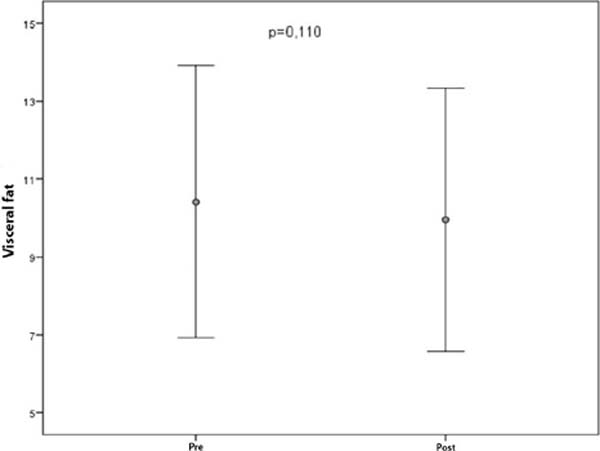

When comparing the average percentage of total body fat, total, visceral, and peripheral fat, there was no statistically significant difference. Weight dropped significantly (p = 0.024) and, as expected, there was also a statistically significant decrease in body mass index (p = 0.017) (Table 1).

| Measurements | Pre | Post | Difference (CI 95%) | p* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % of body fat total | 31.4±7.81 | 30.95±7.86 | −0.59 (−1.83 to 0.66) | 0.339 |

| Total fat | 22.38±6.15 | 21.57±6.00 | −0.80 (−1.94 to 0.33) | 0.156 |

| Visceral fat | 10.42±3.49 | 9.96±3.38 | −0.46 (−1.03 to 0.11) | 0.110 |

| Peripheral fat | 21.14±5.93 | 20.40±5.89 | −0.74 (−1.86 to 0.38) | 0.183 |

| Weight | 70.91±7.19 | 69.36±7.17 | −1.55 (−2.88 to 0.22) | 0.024 |

| Body Mass Index | 27.00±2.39 | 26.40±2.60 | −0.60 (−1.09 to 0.12) | 0.017 |

Interpretation: For example, the average total body fat percentage was 31.54% before surgery and decreased to 30.95%. It fell by an average of 0.59, and with 95% confidence, the average difference is a number that goes from −1.83 (the negative sign shows that it decreased) to an increase of 0.66 (because the upper limit of the range has a positive sign). So, the average variation could be a decrease and could even be a small increase. There was no significant difference (because p is greater than 0.05).

Of 13 patients with visceral fat greater than or equal to 10, 3 (23.1%) had visceral fat below 10.

In the following mean and error bar graphs, where the circle represents the mean and the bar represents the standard deviation, the results of the comparison of measurements before and after surgery are presented (Figures 1 and 2).

When evaluating the correlation between the change in peripheral and visceral fat, this correlation was statistically significant, direct, and strong (r=0.89; p<0.001). For a variation of 1 unit of peripheral fat, visceral fat varies by 0.46 units. When evaluating the correlation between the change in the percentage of total and visceral fat, this correlation was statistically significant, direct, and strong (r=0.84; p<0.001). For a variation of 1 unit, the percentage of total body fat varies by 0.38 units in visceral fat (Figure 3).

DISCUSSION

Obesity is currently a globally prevalent disease and its treatments are increasingly refined and optimized. Bariatric surgery is one of the fastest-growing procedures today, and even without large studies, post-bariatric plastic surgery brings excellent aesthetic and restorative benefits to the health of these patients.

Some studies show that post-obesity surgery plastic surgery helps maintain weight loss in the long term. The reasons for this are not known, but we believe that plastic surgery provides reasons for patients to continue taking care of themselves or that the profile of the patient who undergoes reconstructive surgery is more prone to postoperative care15. Concerning quality of life, several studies highlight the importance that reconstructive surgery has in improving both self-esteem and health in this group of patients11.

In the present study, we were able to observe that patients who underwent dermolipectomy lost more weight and, consequently, lowered their muscle mass indexes, which is compatible with the removal of dermoadipose tissue during the procedure. This corroborates the initial hypothesis and we know that only the surgical procedure can perform this correction of excess tissue.

In relation to the percentage of body fat, peripheral fat, visceral fat, and total fat, although not statistically significant, there was a reduction in absolute numbers. The reason for not alternating more values may be related to weight regain, which occurs mainly after 2 years of bariatric surgery15. Another issue may be stopping physical activities due to the postoperative period. This issue can be better elucidated with longer postoperative follow-up or other studies that better evaluate these parameters.

Finally, we were able to observe that there is a direct, strong, and statistically significant correlation between the percentage of body fat and visceral fat, in addition to the same happening with peripheral fat and visceral fat. This shows that the patient who loses the most peripheral fat loses the most visceral fat, which is the fat related to various diseases and health problems. This correlation opens up the possibility of new studies to evaluate another benefit of reconstructive plastic surgery, which is its clinical impact on bariatric patients.

CONCLUSION

In the present study, we can conclude that the percentage of body fat did not change significantly before and after plastic surgery. However, there is a decrease in this percentage of fat, and even though it is not statistically significant, it is directly proportional to the decrease in visceral fat, which is the fat that most impacts our health. With this, we can say that post-bariatric plastic surgery, among many benefits, has a positive impact on the body composition of patients.

REFERENCES

1. Associação Brasileira para o Estudo da Obesidade e Síndrome Metabólica (ABESO). Obesidade e Sobrepeso. São Paulo: ABESO; 2020. Disponível em: https://abeso.org.br/conceitos/obesidade-e-sobrepeso/

2. Beato GC, Ravelli MN, Crisp AH, de Oliveira MRM. Agreement Between Body Composition Assessed by Bioelectrical Impedance Analysis and Doubly Labeled Water in Obese Women Submitted to Bariatric Surgery: Body Composition, BIA, and DLW. Obes Surg. 2019;29(1):183-9.

3. Agha-Mohammadi S, Hurwitz DJ. Nutritional deficiency of post-bariatric surgery body contouring patients: what every plastic surgeon should know. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;122(2):604-13.

4. Das SK, Roberts SB, Kehayias JJ, Wang J, Hsu LK, Shikora SA, et al. Body composition assessment in extreme obesity and after massive weight loss induced by gastric bypass surgery. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2003;284(6):E1080-8.

5. Kyle UG, Bosaeus I, De Lorenzo AD, Deurenberg P, Elia M, Gómez JM, et al., Composition of the ESPEN Working Group. Bioelectrical impedance analysis--part I: review of principles and methods. Clin Nutr. 2004;23(5):1226-43.

6. Kyle UG, Bosaeus I, De Lorenzo AD, Deurenberg P, Elia M, Manuel Gómez J, et al., ESPEN. Bioelectrical impedance analysis-part II: utilization in clinical practice. Clin Nutr. 2004;23(6):1430-53.

7. Mulasi U, Kuchnia AJ, Cole AJ, Earthman CP. Bioimpedance at the bedside: current applications, limitations, and opportunities. Nutr Clin Pract. 2015;30(2):180-93.

8. Associação Médica Brasileira (AMB). Diretrizes da Avaliação da composição corporal. São Paulo: AMB. Disponível em:_https://diretrizes.amb.org.br/_DIRETRIZES/Avaliação_da_Composição_ Corporal_por_Bioimpedanciometria_(BIA)_aut_autores_/O<%20Meu%20Catalogo/files/assets/common/downloads/publication.pdf

9. Nicoletti CF Camelo JS Jr, dos Santos JE, Marchini JS, Salgado W Jr, Nonino CB. Bioelectrical impedance vector analysis in obese women before and after bariatric surgery: changes in body composition. Nutrition. 2014;30(5):569-74.

10. Wiser I, Avinoah E, Ziv O, Parnass AJ, Averbuch Sagie R, Heller L, et al. Body contouring surgery decreases long-term weight regain following laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding: A matched retrospective cohort study. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2016;69(11):1490-6.

11. Barone M, Cogliandro A, Salzillo R, Tambone V, Persichetti P Patient-Reported Satisfaction Following Post-bariatric Surgery: A Systematic Review. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2018;42(5):1320-30.

12. Zuelzer HB, Baugh NG. Bariatric and body-contouring surgery: a continuum of care for excess and lax skin. Plast Surg Nurs. 2007;27(1):3-13.

13. Balagué N, Combescure C, Huber O, Pittet-Cuénod B, Modarressi A. Plastic surgery improves long-term weight control after bariatric surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;132(4):826-33.

14. de Zwaan M, Georgiadou E, Stroh CE, Teufel M, Köhler H, Tengler M, et al. Body image and quality of life in patients with and without body contouring surgery following bariatric surgery: a comparison of pre- and post-surgery groups. Front Psychol. 2014;5:1310.

15. Smith OJ, Hachach-Haram N, Greenfield M, Bystrzonowski N, Pucci A, Batterham RL, et al. Body Contouring Surgery and the Maintenance of Weight-Loss Following Roux-En-Y Gastric Bypass: A Retrospective Study. Aesthet Surg J. 2018;38(2):176-82.

1. Hospital São Lucas da PUCRS, Division of Obesity and Metabolic Syndrome, Porto

Alegre, RS, Brazil

2. Hospital São Lucas da PUCRS, Division of Plastic Surgery, Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil

3. Hospital Geral, Division of Surgery, Caxias do Sul, RS, Brazil

Corresponding author: Matheus Piccoli Martini Av. Ipiranga, 6690 - Partenon, Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil. Zip Code: 90610-001. E-mail: martini_matheus@hotmail.com

Read in Portuguese

Read in Portuguese

Read in English

Read in English

PDF PT

PDF PT

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to Cite

How to Cite

Mendeley

Mendeley

Pocket

Pocket

Twitter

Twitter