Original Article - Year 2024 - Volume 39 -

Rectified Pulley Suture for the synthesis of tensioned skin wounds

Sutura em Polia Retificada para síntese de feridas de pele tensionadas

ABSTRACT

Introduction: The synthesis of tensioned skin wounds is an area that has been the subject of studies for the development of suturing techniques that are capable of performing the primary closure of these wounds with tension relief, ensuring adequate healing, and avoiding complications such as dehiscence, edema, bleeding, and infection.

Method: This research was a pilot study, being the first presentation of the Rectified Pulley Suture technique for the synthesis of tensioned skin wounds through prospective, double-blind monitoring of a series of cases of 8 patients randomly admitted to the surgical center of a high-complexity hospital in a mediumsized city.

Results: Rectified Pulley Suture is a versatile technique suitable for dealing with tensioned skin wounds, since intraoperatively it was able to close, by first intention, lesions measuring up to 6.5 centimeters and in different tensioned regions without the need for the use of more extensive techniques. complex, such as flaps, grafts, Z-plasty, and secondary intention closure. Furthermore, post-operatively, there was a reduction in POSAS scores, indicating a satisfactory healing process for both observers and the patient. It is also essential to mention that the most feared outcome in the follow-up of patients with tension wounds undergoing primary closure - dehiscence - was completely avoided.

Conclusion: The technique is simple, reliable, safe, and reproducible, with a short learning curve, so the Rectified Pulley Suture can be considered a new tool to be integrated into the surgical arsenal.

Keywords: Wound closure techniques; Surgical wound dehiscence; Cicatrix; Suture techniques; Surgical procedures, operative.

RESUMO

Introdução: A síntese de feridas de pele tensionadas é uma área que tem sido alvo de estudos para o desenvolvimento de técnicas de sutura que sejam capazes de realizar o fechamento primário dessas feridas com alívio de tensão, garantindo uma cicatrização adequada e evitando complicações como deiscência, edema, sangramento e infecção.

Método: Esta pesquisa tratou-se de um estudo piloto, sendo a primeira apresentação da técnica de Sutura em Polia Retificada para síntese de feridas de pele tensionadas através do acompanhamento prospectivo, duplo-cego, de uma série de casos de 8 pacientes randomicamente admitidos no centro cirúrgico de um hospital de alta complexidade de uma cidade de médio porte.

Resultados: A Sutura em Polia Retificada é uma técnica versátil e apta para lidar com feridas de pele tensionadas, uma vez que no intraoperatório conseguiu fechar por primeira intenção lesões de até 6,5 centímetros e de diferentes regiões tensionadas sem necessidade do uso de técnicas mais complexas, como retalhos, enxertos, zetaplastia e fechamento por segunda intenção. Além disso, no pós-operatório, houve redução dos escores da POSAS, indicando um processo de cicatrização satisfatório tanto para os observadores quanto para o paciente. É imprescindível mencionar, também, que o desfecho mais temido no seguimento dos pacientes com feridas tensionadas submetidos a fechamento primário - a deiscência - foi completamente evitado.

Conclusão: A técnica é simples, confiável, segura e reprodutível, com curta curva de aprendizagem, de forma que a Sutura em Polia Retificada pode ser considerada como uma nova ferramenta a ser integrada ao arsenal cirúrgico.

Palavras-chave: Técnicas de fechamento de ferimentos; Deiscência da ferida operatória; Cicatriz; Técnicas de sutura; Procedimentos cirúrgicos operatórios.

INTRODUCTION

Tensioned skin wounds are tissue continuity solutions resulting from extensive debridement or significant tissue loss, as occurs in the surgical excision of skin tumors or nevus, mainly in the scalp, chest, back, and extremities region1,2. The synthesis of these tension wounds is an area that has been the subject of studies for the development of suturing techniques that are capable of performing the primary closure of these wounds with tension relief, ensuring adequate healing and avoiding complications, such as dehiscence, edema, bleeding, and infection1.

Traditionally, “vertical mattress” (Donatti suture, or far-far-near-near) or “horizontal mattress” (U-shaped suture) sutures are used, both of which approximate the subcutaneous tissue and provide eversion of the edges, ensuring more adequate healing1. Furthermore, these sutures that involve the subcutaneous tissue have a lower incidence of incisional surgical site infection3. However, it is worth pointing out that both sutures can cause excessive tensile force at the edges of the wound, leading to tissue ischemia and a greater risk of dehiscence. Because of this, it is possible to apply these sutures only at the site of maximum wound tension, interspersing other discontinuous points in the rest of the wound4.

Despite being widely known and implemented, these traditional sutures have undergone adaptations that have brought new mechanical advantages for relieving tension when closing tensioned surgical wounds, such as the “pulley suture”5 (pulley suture or “far-near-near-far”), in which its 4 insertion points act as 4 pulleys, reducing tension by 25% at each point6, which, in addition to relieving tension and facilitating the approximation of the wound edges, also presented other reported advantages, such as better hemostasis during the procedure and general reduction in time and cost to perform the suture6,7.

Aware of these benefits of pulley sutures for closing tensioned skin wounds, other authors described adaptations with the pulley principle, such as: “tandem pulley stitch”8; “pulley set-back dermal suture”9; “modified winch stitch suture”10; and “double-butterfly”11.

However, to improve pulley suturing and further prevent the risk of wound dehiscence, the vast majority of these techniques have become complex, difficult to handle and apply, often requiring innovative instruments for complete implementation. In fact, when tying the knots and finalizing these complex sutures that deal with such tension, other techniques for tying the knots were created, such as the “double loop-dermal suture”12; and the “loma-linda loop”13. Still others require different materials and two surgical stages, such as “elastic sutures”14,15.

Thus, analyzing the current scenario, the literature shows that there are other suturing possibilities with additional advantages when applying the pulley principle. Given the new complex possibilities, the authors propose a simpler adaptation of the “pulley suture”, with a small learning curve, which still uses the principle of pulleys to relieve tension, combined with subcutaneous insertions to reduce the risk of incisional infection of the surgical site, adequate coaptation of the edges to provide an aesthetic scar, and ease of tying the knots to optimize intraoperative time, called “Rectified Pulley Suture”, that is, an improvement on the “pulley suture”.

OBJECTIVE

The authors, when analyzing the current panorama of suturing techniques already developed for tensioned skin wounds, used their theoretical-practical foundations to develop and improve a skin suture that uses the pulley principle, called Rectified Pulley Suture. This study aimed to describe the Rectified Pulley Suture and evaluate its versatility and applicability for closing tensioned skin wounds and, thus, integrating into the surgeon’s arsenal a new suturing technique that is easy to perform, fast, scientifically based, and safe, which in many cases can be an alternative to more complex techniques, such as other sutures and even flaps, grafts and Z-plasty.

METHOD

This is an observational study of the results of a series of prospective cases, approved by the Ethics and Research Committee of UniCesumar (CAAE 63832322.3.0000.5539), and carried out at the Surgical Center of the Oncology Department of Hospital Santa Rita, in Maringá-PR, upon declaration of authorization from the location.

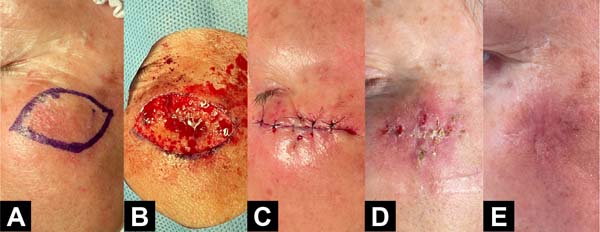

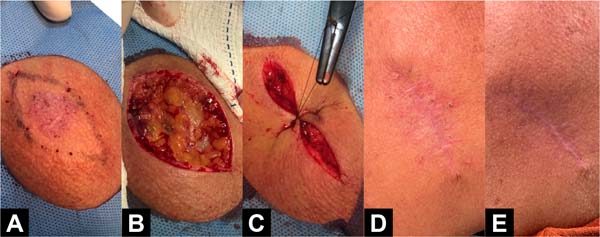

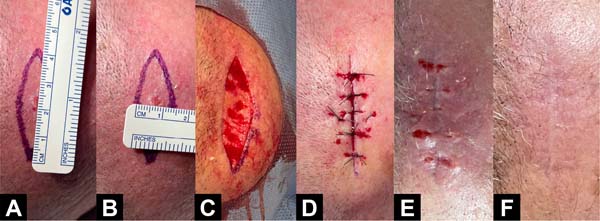

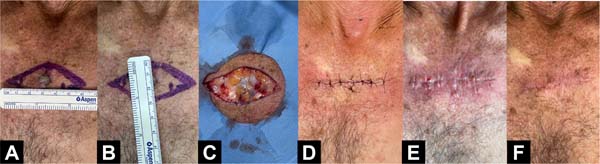

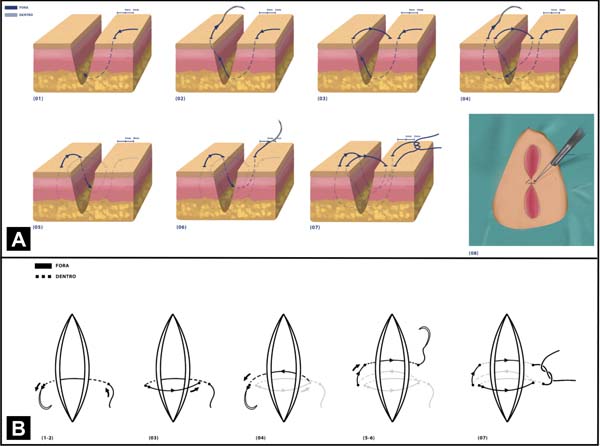

The Rectified Pulley Suture technique consists of 7 steps, which can be seen in Figure 1: 1) the needle is inserted approximately 8 millimeters (mm) from the edge of the wound (“far”); 2) the needle is taken to the opposite side of the wound and inserted approximately 4mm from the contralateral edge (“near”); 3) the needle is again brought to the initial edge, but this time it is inserted 4mm from the edge (“near”); 4) to complete the pulley, the needle is inserted 8mm from the contralateral (“far” edge); 5) the needle is then inserted again into the contralateral edge and 4mm from the edge (“near”), however, this time in a line parallel to the already formed pulley; 6) still in this parallel line, the needle is inserted approximately 4mm into the edge of the beginning of the technique (“near”); 7) creation of the double surgeon’s knot with the aid of a needle holder to complete the suture.

The addition of 2 new insertion points (steps 5 and 6, “near-near”) in a suture line parallel to the pulley construction line (steps 1, 2, 3, and 4; “far-near-near-far ”), when compared to the “pulley suture”, facilitates the distribution of tension throughout the wound, improves the coaptation of the edges and also facilitates the creation of a double surgeon’s knot without the need for specific surgical instruments or the contribution of an auxiliary doctor ( since the “start” and “end” of the technique are located on the same edge of the wound).

Patients randomly admitted over the period from 02/17/2023 to 04/24/2023 were recruited considering the following inclusion criteria: 1) adults over 18 years old, of both sexes, of all ethnicities, literate and non-literate -literate, without socioeconomic distinction; 2) adults capable of understanding the benefits, risks and consequences of study participation and capable of providing informed consent; 3) present skin wounds measuring 1-10 centimeters in areas of great tension, such as the back, chest, scalp, face, upper and lower limbs, capable of being subjected to primary closure.

Patients with keloids, hypertrophic scars, autoimmune or immunosuppressive diseases, or using corticosteroids, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, immunosuppressants, or who required other surgical techniques such as flaps, grafts, or Z-plasty were excluded. However, patients with poor nutritional status, smokers, alcoholics, or those with other non-infectious chronic diseases were not excluded from the study.

Those who met the inclusion criteria were invited to participate in the research and, upon signing the Informed Consent Form, underwent implementation of the Rectified Pulley Suture by a qualified surgeon, totaling 8 patients.

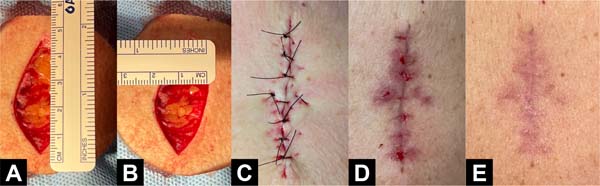

The technique was performed at the point of greatest tension in the wound (i.e., in the center), while the ends of the wound could be sutured with other discontinuous stitches, all of which used 3-0 monofilament nylon thread (Mononylon Ethilon; Ethicon ), which is a monofilament thread, non-absorbable, versatile, strong, capable of reducing tissue traction and with a lower risk of developing postoperative infection when compared to multifilament threads, as it presents greater biostability16. Photographs of the tensioned wounds were recorded throughout the technique implementation procedure, its immediate and postoperative results, as documentation and demonstration of the suture. The wounds were measured with a surgical ruler considering their largest and smallest dimensions.

Postoperatively, all patients were instructed on daily wound care (cleaning and maintaining dressings, use of simple analgesics), and on the following restrictions: the use of healing ointments, immunosuppressants, and steroidal anti-inflammatories was not permitted. or corticosteroids; as well as it was not allowed to scratch the area or even remove the stitches early on your own, as the removal of stitches took place between 2-3 weeks, together with the reevaluation of the wound.

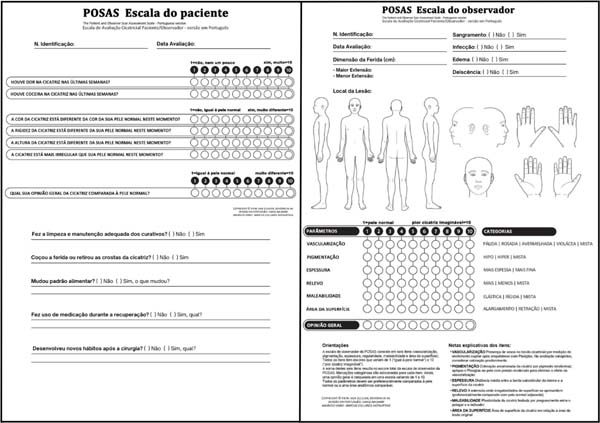

Then, to document the versatility and applicability of the Rectified Pulley Suture, the scarring process was assessed using the Patient and Observer Cicatricial Assessment Scale (POSAS) translated into Portuguese17 on two occasions: the first between 15° to the 21st day after implementing the technique (along with the removal of stitches), and the second between the 60th to 90th day.

POSAS uses subjective parameters in an objective manner and is considered a reliable, viable, consistent, valid, and innovative scale that, in addition to considering the observer’s opinion, gives weight to the patient’s opinion as an evaluator, having received the best evaluations in reviews18 ,19. POSAS includes two scales (patient and observer), shown in Figure 2, both of which contain 6 items that can be individually scored from 1 (scar similar to normal skin) to 10 (worst scar or sensation imaginable), whose final scores are each of the scales from the sum of the individual items ranges from 6 (reflecting normal skin) to 60 (worst imaginable scar).

Among the parameters evaluated on the observer scale are: vascularization, pigmentation, thickness, relief, malleability, and surface area. Among the items evaluated on the patient scale are: pain, itching, color, stiffness, thickness, and relief. Furthermore, both the observer and the patient can give a general opinion of the scar compared to normal skin, whose score also varies from 1 (same as normal skin) to 10 (worst imaginable scar). It is worth mentioning that the patient scale was filled out by the patients themselves with the help of a photograph when the wound could not be directly visualized, and non-literate patients received assistance with reading and recording. The observer scale was applied in a randomized, double-blind, and non-simultaneous manner17.

A patient identification questionnaire was also compiled regarding identification number (n), age, sex, ethnicity, origin, profession, monthly personal income, education, medications for continuous use and sporadic use, comorbidities, and lifestyle habits. Furthermore, in addition to the parameters of the observer’s scale and the questionnaire applied, other parameters and outcomes were noted regarding their presence (yes or no) such as infection and dehiscence, and graded as crosses (1+/4+) such as bleeding and edema. Also, to complement the patient’s scale, they were asked about cleaning and maintenance of dressings, handling the wound, changing eating patterns, developing new habits, and using medications post-operatively.

Data relating to POSAS were gathered, tabulated, and analyzed based on the Observer Total Score (OTS), Observer General Opinion Score (OOS), Patient Total Score (PTS), and Patient General Opinion Score (POS), based on the information collected in the patient identification questionnaire, to produce data compilation tables and descriptive analysis, to document the favorable and unfavorable outcomes of the suturing technique17.

RESULTS

The sample consisted of 8 patients who underwent excision of skin tumors in different tension regions, both non-melanoma cancer and melanoma. Among them, there were 4 men and 4 women, all of white ethnicity, aged 52 to 76 years, with an average age of 65 years. Regarding the location of the wounds, they were all different, including the sternal, brachial, back of the hand, tibial, dorsal, scalp, and malar region of the face (different regions were chosen to demonstrate versatility). Regarding the size of the wounds, they ranged from 3.4 to 6.5cm in the largest diameter (average of 5.0cm) and from 1.4 to 5.0cm in the smallest diameter (average of 2.5cm). The complete demographic profile is listed in Table 1.

| n | Age | Sex | Ethnicity | Wound Location | Dimensions (cm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 55 | Masculine | White | Malar Left | 3.4 x 2.0 |

| 2 | 64 | Feminine | White | Back Face Left Arm | 6.5 x 5.0 |

| 3 | 52 | Feminine | White | Right Medial Tibial Surface | 5.8 x 2.0 |

| 4 | 73 | Masculine | White | Left Back | 6.0 x 2.5 |

| 5 | 63 | Masculine | White | Posterior Left Parietal Scalp | 4.0 x 1.4 |

| 6 | 64 | Masculine | White | Sternal | 6.0x 2.8 |

| 7 | 76 | Feminine | White | Dorsal Face Right hand | 4.2x 2.5 |

| 8 | 74 | Feminine | White | Side Face Left arm | 4.2x 1.6 |

Abbreviation: n=patient identification number in the study.

In the first assessment, concerning the observer scale, the OTS, calculated from the average between the scores of observers 1 and 2, ranged from 16.0 to 35.5 points (average of 22.5); the OOS, also calculated from the average of the observers’ scores, ranged from 2.5 to 6.5 points (average of 4.0). Regarding the patient scale, the PTS ranged from 8.0 to 35.0 points, with an average of 21.6. The POS ranged from 1.0 to 8.0 points (average of 3.9). Regarding outcomes, no patient presented dehiscence of the stitches; only two patients (4 and 7) had surgical site infections; four reported mild bleeding in the first postoperative days (1, 3, 5, and 7); and three presented edema (1, 4 and 7), two of which reported considerable edema (4 and 7). The individual scores and outcomes of the first assessment can be seen in Table 2.

| n | OTS OTS1 OTS2 OTSm |

OOS OOS1 OOS2 OOSm |

PTS | POS | S | I | E | D | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 21 | 22 | 21.5 | 4 | 3 | 3.5 | 14 | 3 | 1+ | No | 1+ | No |

| 2 | 18 | 18 | 18 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 16 | 3 | 0 | No | 0 | No |

| 3 | 34 | 37 | 35.5 | 7 | 6 | 6.5 | 32 | 8 | 2+ | No | 0 | No |

| 4 | 19 | 15 | 17 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 8 | 1 | 0 | Yes | 3+ | No |

| 5 | 13 | 19 | 16 | 2 | 3 | 2.5 | 18 | 2 | 1+ | No | 0 | No |

| 6 | 24 | 25 | 24.5 | 5 | 4 | 4.5 | 30 | 4 | 0 | No | 0 | No |

| 7 | 26 | 28 | 27 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 35 | 5 | 1+ | Yes | 3+ | No |

| 8 | 20 | 21 | 20.5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 20 | 5 | 0 | No | 0 | No |

OTS1=Total Score of Observer 1; OTS2=Total Score of Observer 2; OTSm=Average of Total Observer Scores; OOS1=Observer 1’s General Opinion Score; OOS2=Observer 2’s General Opinion Score; OOS=Average of Observers’ General Opinion Scores; PTS=Total Patient Score; POS=Overall Patient Opinion Score; S=Bleeding; I=Infection; E=Edema; D=Dehiscence.

In the second assessment, in relation to the observer’s scale, the OTS ranged from 14.0 to 23.5 points (average of 17.4; reduction of 5.1 points or -9.4% in relation to the first meeting); the OOS ranged from 2.0 to 4.5 points (average of 3.3, reduction of 0.7 points or -7.8% in relation to the first assessment). In relation to the POSAS patient scale, the PTS ranged from 8.0 to 35.0 points, with an average of 15.8, and a reduction of 5.8 points or -10.7% in relation to the first encounter. The POS varied from 1.0 to 6.0 points (average of 3.0, reduction of 0.9 points or -9.9% in relation to the first assessment). Patients who presented any of the unfavorable outcomes in the first evaluation had complete resolution and no new complications. The remaining patients also did not present new outcomes. The scores and individual outcomes of the second assessment can be seen in Table 3.

| n | OTS OTS1 OTS2 OTSm |

OOS OOS1 OOS2 OOSm |

PTS | POS | S | I | E | D | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 21 | 15 | 18 | 4 | 3 | 3.5 | 22 | 2 | 0 | No | 0 | No |

| 2 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 10 | 2 | 0 | No | 0 | No |

| 3 | 21 | 26 | 23.5 | 4 | 5 | 4.5 | 19 | 5 | 0 | No | 0 | No |

| 4 | 18 | 16 | 17 | 4 | 3 | 3.5 | 8 | 1 | 0 | No | 0 | No |

| 5 | 12 | 15 | 13.5 | 2 | 3 | 3.5 | 8 | 2 | 0 | No | 0 | No |

| 6 | 18 | 14 | 16 | 3 | 2 | 2.5 | 12 | 2 | 0 | No | 0 | No |

| 7 | 21 | 18 | 19.5 | 4 | 3 | 3.5 | 12 | 4 | 0 | No | 0 | No |

| 8 | 17 | 19 | 18 | 4 | 3 | 3.5 | 35 | 6 | 0 | No | 0 | No |

OTS1=Total Score of Observer 1; OTS2=Total Score of Observer 2; OTSm=Average of Total Observer Scores; OOS1=Observer 1’s General Opinion Score; OOS2=Observer 2’s General Opinion Score; OOS=Average of Observers’ General Opinion Scores; PTS=Total Patient Score; POS=Overall Patient Opinion Score; S=Bleeding; I=Infection; E=Edema; D=Dehiscence.

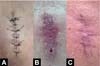

Photographic examples of the implementation of the Rectified Pulley Suture and the postoperative scar evolution are shown in Figures 3 to 10.

DISCUSSION

Although the research has limitations, such as short time for sample selection and monitoring, small sample size, impossibility of microscopic analysis of healing, lack of control group, impossibility of comparative analysis of the technique with other threads or in relation to other suturing techniques in the same study, it fulfilled its objective of presenting the technique and demonstrating its versatility and applicability in different contexts of resolving tension skin wounds.

This statement can be validated when considering the positive evolution of the scores, in which the reduction in the average score of all scores in the second evaluation (Table 3) in relation to the first (Table 2) demonstrates improvement in the healing process and suture suitability in Rectified Pulley, taking into account the analysis of observers and the patient, since the values closer to 1, the closer they are to normal skin and the best outcome imaginable.

Observers noted that the technique is simple, reliable, safe, and reproducible, with a short learning curve, so the Rectified Pulley Suture can be considered a new tool to be integrated into the arsenal of medical students, general practitioners, and surgeons. specialists, since techniques such as “pulley set-back dermal suture”9, “double-butterfly”11, “double loop-dermal suture”12 and the “loma-linda loop”13 have proven to be difficult to apply and have a long learning curve.

These results and observations regarding the Rectified Pulley Suture were consistent with the results of Kannan et al.7, who demonstrated a mechanical advantage of tension relief, ease of approximation of the wound edges, better hemostasis during the procedure, general reduction in time and the cost of creating the technique and reducing POSAS scores throughout the healing process using a suture with the pulley principle. Furthermore, it was noticed that the more pulleys were inserted, the greater the tension relief throughout the wound, further increasing the mechanical advantage for wounds with little tissue to approach the edges, something that was also noted in patients 3 and 4 7,8,10.

Furthermore, it is necessary to pay attention to local and general factors that negatively interfere with the healing process, and which can predispose to the main complications: bleeding, edema, infection, and dehiscence. Local factors are related to the condition of the wound and how it is treated surgically. General factors, on the other hand, are related to the patient’s clinical conditions20-22.

In line with this, the infection observed in patient 4 can be, at least in part, justified by the smoking habit, which negatively influences the healing process through vasoconstriction, tissue ischemia, reduced inflammatory response, impaired bactericidal mechanisms, and alteration of the metabolism of collagen, increasing the likelihood of dehiscence and surgical site infection23,24.

Furthermore, the occurrence of edema associated with infection reinforces that the Rectified Pulley Suture was able to handle tension beyond that expected intraoperatively. In the case of patient 7, there was a greater risk of infection and dehiscence, since the surgical wound had distant edges, which did not follow Kraissl’s skin tension lines25 and, even with tissue flaccidity, contained little tissue for approximation. Furthermore, the hand is a region of great exposure and mobility which, combined with incorrect wound hygiene and inadequate maintenance of dressings reported by the patient and companion, resulted in infection with crusted formation. Even with this adverse outcome, the Rectified Pulley Suture distributed the tension and contributed to adequate healing2.

In general, the evolution of the scores of all patients shows that the suture is capable of promoting significant improvement in wounds in different regions and patients of different sexes, ages, and comorbidities. Furthermore, it provided additional advantages for those who, for some reason, did not have the same care with sutures, dressings, or health conditions.

CONCLUSION

The Rectified Pulley Suture is a versatile technique, with the ability to deal with tensioned skin wounds, since intraoperatively it was able to nearby first intention lesions with dimensions of up to 6.5cm in the largest diameter and in different tensioned regions without the need for use of more complex techniques, such as flaps, grafts, Z-plasty, and secondary intention closure. Furthermore, post-operatively, there was a reduction in POSAS scores, which indicates a satisfactory healing process and good evolution for both observers and the patient.

It is also essential to mention that the most feared outcome in the follow-up of patients with tension wounds undergoing primary closure - dehiscence - was completely avoided in our sample, even though other outcomes that further increase the risk of dehiscence were present, such as infection, edema, and bleeding. The possibility of dealing with these complications and remaining intact is more relevant than their absence, which suggests the Rectified Pulley Suture as a safe technique in the face of the adverse outcomes of tensioned skin wounds.

REFERENCES

1. Singh R, Hawkins W. Sutures, ligatures and knots. Surgery (Oxford). 2020;38(3):123-7. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.mpsur.2020.01.003

2. Tazima MFGS, Vicente YAMVA, Moriya T. Biologia da ferida e cicatrização. Medicina (Ribeirão Preto Online). 2008;41(3):259-64. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.11606/issn.2176-7262.v41i3p259-264

3. Okubo S, Gotohda N, Sugimoto M, Nomura S, Kobayashi S, Takahashi S, et al. Abdominal skin closure using subcuticular sutures prevents incisional surgical site infection in hepatopancreatobiliary surgery. Surgery. 2018;164(2):251-6. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2018.04.002

4. Hochberg J, Meyer KM, Marion MD. Suture choice and other methods of skin closure. Surg Clin North Am. 2009;89(3):627-41. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.suc.2009.03.001

5. Hitzig GS, Sadick NS. The pulley suture. Utilization in scalp reduction surgery. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1992;18(3):220-2. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1524-4725.1992.tb02802.x

6. Yang DJ, Venkatarajan S, Orengo I. Closure pearls for defects under tension. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36(10):1598-600. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1524-4725.2010.01690.x

7. Kannan S, Mehta D, Ozog D. Scalp Closures With Pulley Sutures Reduce Time and Cost Compared to Traditional Layered Technique-A Prospective, Randomized, Observer-Blinded Study. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42(11):1248-55. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/dss.0000000000000890

8. Lee CH, Wang T. A novel suture technique for high-tension wound closure: the tandem pulley stitch. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41(8):975-7. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/dss.0000000000000422

9. Kantor J. The pulley set-back dermal suture: an easy to implement everting suture technique for wounds under tension. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72(1):e29-30. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2014.09.001

10. Casparian JM, Rodewald EJ, Monheit GD. The “modified” winch stitch. Dermatol Surg. 2001;27(10):891-4. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1524-4725.2001.01107.x

11. Breuninger H. Double butterfly suture for high tension: a broadly anchored, horizontal, buried interrupted suture. Dermatol Surg. 2000;26(3):215-8. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1524-4725.2000.09190.x

12. Pollhammer MS, Duscher D, Schmidt M, Aitzetmüller MM, Tschandl P, Froschauer SM, et al. Double-Loop Dermal Suture: A Technique for High-Tension Wound Closure. Aesthet Surg J. 2016;36(4):NP165-7. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/asj/sjv230

13. Young PA, Zumwalt JR. The Loma Linda loop: A closure technique for high-tension wounds. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86(2):e45-e46. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2021.08.025

14. Fraga DS, Pretto AL, Silva YPD. Sutura elástica: uma opção no tratamento de extensas perdas cutâneas. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2019;34(1):148-50. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5935/2177-1235.2019RBCP0023

15. Santos ELN, Oliveira RA. Sutura elástica para tratamento de grandes feridas. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2012;27(3):475-7. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/S1983-51752012000300026

16. Sofii I, Kalembu RS, Fauzi AR, Makrufardi F, Makhmudi A. TGF-β expression on different suturing technique for abdominal skin wound closure in rats. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2021;67:102521. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amsu.2021.102521

17. Linhares CB, Viaro MSS, Collares MVM. Portuguese translation of Patient and Observer Scar Assessment Scale (POSAS). Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2016;31(1):95-100. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5935/2177-1235.2016rbcp0014

18. Durani P, McGrouther DA, Ferguson MW. Current scales for assessing human scarring: a review. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2009;62(6):713-20. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bjps.2009.01.080

19. Choo AMH, Ong YS, Issa F. Scar Assessment Tools: How Do They Compare? Front Surg. 2021;8:643098. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3389/fsurg.2021.643098

20. Armstrong DG, Boulton AJM, Bus SA. Diabetic Foot Ulcers and Their Recurrence. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(24):2367-75. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/nejmra1615439

21. Mills JL Sr, Conte MS, Armstrong DG, Pomposelli FB, Schanzer A, Sidawy AN, et al.; Society for Vascular Surgery Lower Extremity Guidelines Committee. The Society for Vascular Surgery Lower Extremity Threatened Limb Classification System: risk stratification based on wound, ischemia, and foot infection (WIfI). J Vasc Surg. 2014;59(1):220-34.e1-2. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jvs.2013.08.003

22. Jones CM, Rothermel AT, Mackay DR. Evidence-Based Medicine: Wound Management. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;140(1):201e-16e. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/prs.0000000000003486

23. Sørensen LT. Wound healing and infection in surgery: the pathophysiological impact of smoking, smoking cessation, and nicotine replacement therapy: a systematic review. Ann Surg. 2012;255(6):1069-79. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/sla.0b013e31824f632d

24. Turan A, Mascha EJ, Roberman D, Turner PL, You J, Kurz A, et al. Smoking and perioperative outcomes. Anesthesiology. 2011;114(4):837-46. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/aln.0b013e318210f560

25. Bland KI, Büchler MW, Csendes A, Garden J, Sarr MG, Wong J. General Surgery: Principles and international practice. New York: Springer-Verlag; 2009.

1. Universidade Unicesumar, Curso de Medicina, Maringá, PR, Brazil

2. Hospital Santa Rita, Departamento de Oncologia, Maringá, PR, Brazil

Corresponding author: Marcos Fernando Tudino Av. Guedner, 1610, Bloco 06, Faculdade de Medicina, Maringá, PR, Brazil, Zip code: 87050-390, E-mail: marcosfernandotudino@gmail.com

Article received: August 8, 2023.

Article accepted: February 4, 2024.

Conflicts of interest: none.

Read in Portuguese

Read in Portuguese

Read in English

Read in English

PDF PT

PDF PT

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to Cite

How to Cite

Mendeley

Mendeley

Pocket

Pocket

Twitter

Twitter