Original Article - Year 2024 - Volume 39 -

Tactile and visual perception in radix augmentation with free fragmented cartilage in rhinoplasty

Percepção tátil e visual no aumento de radix com cartilagem fragmentada livre na rinoplastia

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Correction of the nasal radix dorsum relationship has been carried out for several years using the most varied techniques such as auricular, septal, or costal cartilage grafts, filling with hyaluronic acid, use of fascia and grafts and the use of diced cartilage, silicone, and hyaluronic acid. The use of fragmented cartilage is described in the literature and has gained popularity in recent years, due to its ease of use. The objective of this study is to describe our experience with the use of fragmented cartilage graft in radix augmentation, comparing the patient's visual and tactile perception and satisfaction.

Method: Observational study in patients undergoing rhinoplasty from January 2018 to June 2022, in surgeries in which the radix was increased with the use of minced cartilage graft.

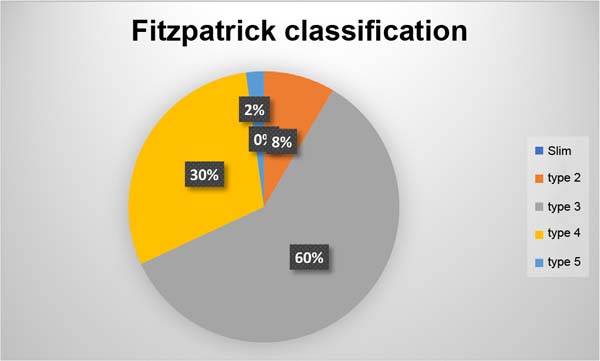

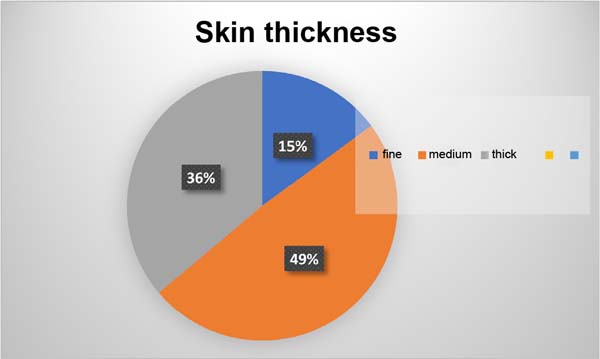

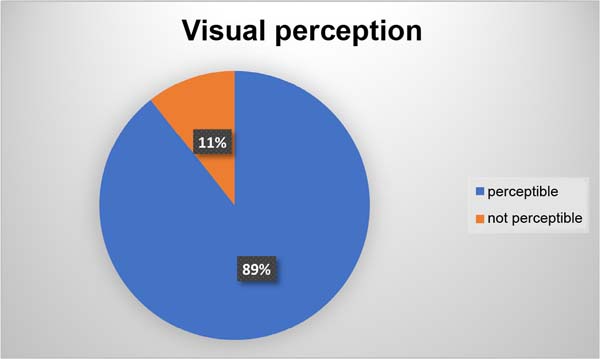

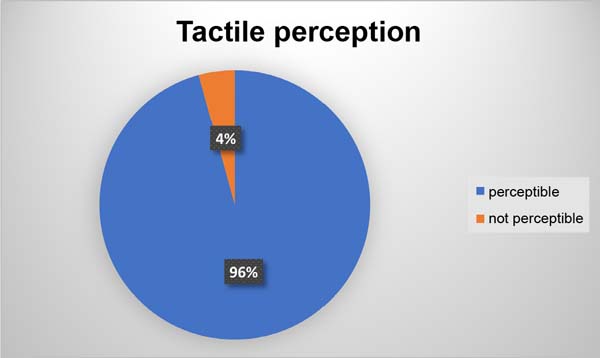

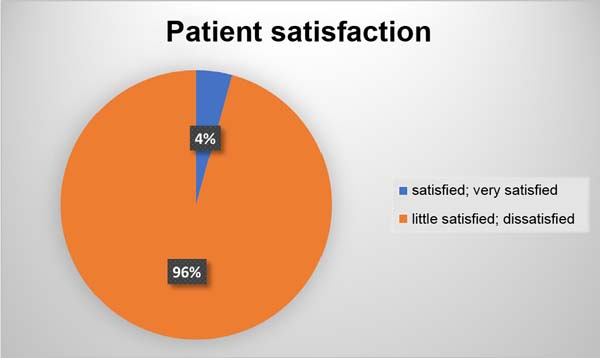

Results: Of the 47 patients, the majority were female (35, 74.4%), with a mean age of 34.6 years (18-44). As for skin type, Fitzpatrick type 3 (n=28, 59.5%) was the main one, with patients with medium-thickness skin being frequently found (n=23, 48.9%). Complications present were infection (1 case), migration of chopped cartilage (3 cases), and partial resorption (1 case). In the assessment of tactile perception, 42 patients (89.3%) perceived cartilaginous prominences on palpation and only 2 (4%) visually. Satisfaction was high in 45 (96%) patients.

Conclusion: Free minced cartilage can be used in the radix region with satisfactory results.

Keywords: Nose; Rhinoplasty; Face; Patient satisfaction; Nose deformities, acquired.

RESUMO

Introdução: A correção da relação radix dorso nasal é realizada há vários anos utilizando as mais variadas técnicas como enxerto de cartilagem auricular, septal ou costal, preenchimento com ácido hialurônico, uso de fáscia e enxertos e uso de cartilagem picada em cubo, silicone e ácido hialurônico. O uso de cartilagem fragmentada é descrito na literatura e tem ganhado adeptos nos últimos anos, pela facilidade em ser realizado. O objetivo neste estudo é descrever nossa experiência com a utilização do enxerto de cartilagem fragmentado no aumento do radix comparando a percepção visual e tátil do paciente e sua satisfação.

Método: Estudo observacional em pacientes submetidos a rinoplastia no período de janeiro 2018 a junho de 2022, em cirurgias nas quais ocorreu o aumento de radix com o uso de enxerto de cartilagem picada.

Resultados: Dos 47 pacientes, a maioria era do sexo feminino (35, 74,4%), com média de idade de 34,6 anos (18-44). Quanto ao tipo de pele, Fitzpatrick tipo 3 (n=28, 59,5%) foi o principal, sendo encontrado frequentemente pacientes com pele de média espessura (n=23, 48,9%). Complicações presentes foram infecção (1 caso), migração de cartilagem picada (3 casos), e reabsorção parcial (1 caso). Na avaliação da percepção tátil 42 pacientes (89,3%) percebiam, à palpação, as proeminências cartilaginosas e na visual apenas 2 (4%). A satisfação foi elevada em 45 (96%) pacientes.

Conclusão: A cartilagem picada livre pode ser utilizada na região do radix com resultados satisfatórios.

Palavras-chave: Nariz; Rinoplastia; Face; Satisfação do paciente; Deformidades adquiridas nasais.

INTRODUCTION

Correction of the nasal radix dorsum relationship has been carried out for several years using the most varied techniques such as auricular, septal, or costal cartilage graft, filling with hyaluronic acid, use of fascia and grafts, and use of diced cartilage, silicone, and hyaluronic acid1-4.

The use of chopped cartilage in the dorsal region began shortly after the Second World War with the work of Gordon & Warren1 and Peer2. Soon after this period, the difficulty in establishing safe criteria to reduce local complications resulted in little use of this resource, and only in the 1990s, the technique was taken up by the work of Erol3-5, with “Turkish delight”, and reproduction by Guerrerosantos et al.6 and Daniel & Calvert7.

With the possibility of reproducibility of the technique described in several studies8-14, there is a description of chopped cartilage placed in planes on the nasal surface, whether or not using muscular fascia.

Cartilage graft is commonly used to augment the nasal dorsum, either as full cartilage or with chopped cartilage. The radix region is one of the main beneficiaries of the use of cartilage in this region, which allows for a back with greater harmony and visual beauty. According to McKinney & Sweis15, the ideal radix height is three-quarters of the nasal length or nasal projection. According to Taş13, the use of chopped cartilage graft in the dorsal region is a way to establish a beautiful and smooth back.

OBJECTIVE

In this study, we analyzed the use of a minced cartilage graft to increase the height of the nasal radix. The use of fragmented cartilage is described in the literature and this technique has gained followers in recent years. The objective is to describe our experience with the use of fragmented cartilage graft to augment the back, comparing visual and tactile perception with patient satisfaction.

METHOD

The study was carried out on patients undergoing rhinoplasty from January 2018 to June 2022, at the Hospital Centro Estadual de Reabilitação e Readaptação Dr. Henrique Santillo, in Goiânia, GO, in surgeries in which the radix was increased with the use of minced cartilage graft, with patients being evaluated 6 months postoperatively.

As exclusion criteria, patients under 18 years of age, with rheumatological comorbidities, and diseases that destroy cartilage such as leishmaniasis, leprosy, and Wegener’s granulomatosis were established.

The study was approved by the hospital’s internal ethics committee and platform Brasil CAEE 30798120.6.0000.5082 and the data were tabulated in Excel 23 (Microsoft®), collecting the following information: age, sex, Fitzpatrick classification, skin thickness, the origin of the graft, complications, tactile perception of the graft and visual perception of the graft and satisfaction with the result.

RESULTS

Forty-seven patients who underwent radix augmentation with minced cartilage were studied. Of these, 35 (74.4%) were female and 12 (25.6%) were male, with a mean age of 34.6 years (18-44).

Regarding Fitzpatrick skin type, they were type 2 (n=4, 8.5%), type 3 (n=28, 59.5%), type 4 (n=14, 29.8%) and type 5 (n =1, 2.2%), with thin skin (n=7, 14.9%), medium skin (n=23, 48.9%) and thick skin (n=17, 36.2%) (Figures 1 and 2).

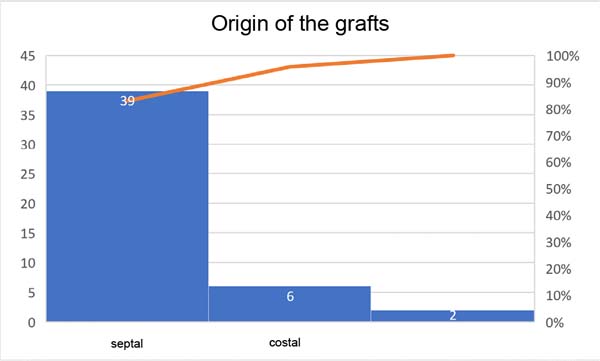

The origin of most grafts was from septal cartilage (n=39, 83%), costal cartilage (n=6, 12.8%), and auricular cartilage (n=2, 4.2%) (Figure 3).

Complications present were infection (1 case), migration of chopped cartilage (3 cases), and partial resorption (1 case).

In the assessment of tactile perception, 42 patients (89.3%) noticed cartilaginous prominences on palpation, but this did not bother them (Figure 4).

In the visual assessment, only 2 patients noticed the irregularity and local scraping was performed with resolution (Figure 5).

Of the patients studied 45 reported satisfaction with the result (very satisfied and satisfied) (Figure 6).

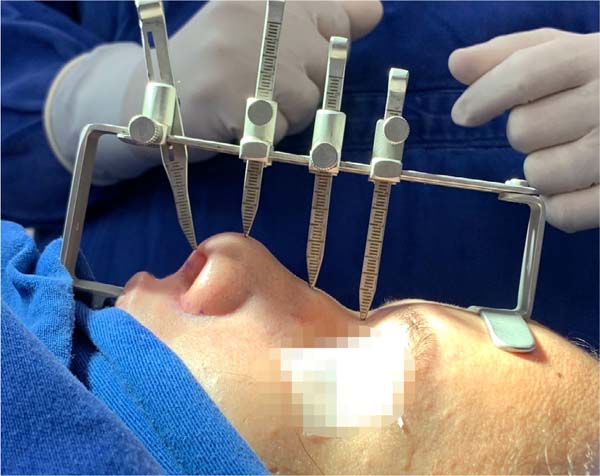

Figures 7 to 13, demonstrate the procedures for preparing the cartilage, its introduction into the radix, and visualization of the result.

DISCUSSION

The first experiments described by Gordon & Warren1 served to validate the technique, showing that the cartilage survived by occupying the space in which it was inserted. From this, several uses were initiated in hernioplasty16, reconstruction of the costal wall17, nose and face18,19 and hip20. The difficulty in reproducing the technique with mastery ended up leaving it forgotten, only being rescued by Erol decades later.

The initial work described by Erol used Surgicel or fascia to house chopped cartilage grafts, in what is known as Turkish delight3. The versatility of sizes and thickness, as well as its use in primary and secondary surgeries, allowed the dissemination of this technique21.

Grafts in the nasal region are part of modern rhinoplasty, being part of reorganizing the structure and improving the shape. The ease of including chopped cartilage without the need for a more rigid fixation such as a Kirschner wire or screw facilitates its use and the possibility of shaping the back due to the malleability of the graft is a superior advantage to the use of an onlay graft.

Vidal et al.12 describe the importance of using chopped cartilage graft in the point, back, and radix relationship, highlighting the importance of using an appropriate technique by detaching an area restricted only to the volume to be grafted, introducing the graft through a syringe 1ml with the tip removed and microporation immediately upon insertion of the graft for adequate molding. In our experience, we agree with these statements and that we can use the syringe developed by Erol instead of the 1ml syringe without harm, in addition to the possibility of a tunnel above the periosteum or perichondrium for insertion of the chopped cartilage.

The perception of cartilage irregularity to the touch is described in other studies21,22, however, this study found that it is not visually perceptible and presents interesting results. Ma et al.23 describe that fragmentation with pieces of cartilage smaller than 0.5 mm reduces the visibility of irregularities, corroborating the results of this study.

The use of onlay cartilage on the radix region may present curves that distort the symmetry of the region or even be perceived as asymmetry and mobilization on palpation. The use of chopped cartilage presents tactile perception, but generally without visual changes. Currently, the use of chopped cartilage can be associated with the use of platelet-rich plasma that creates a continuous and unified structure, which can be a solution for both tactile perception and avoiding migration.

The study has limitations such as the follow-up being only 6 months, which can invariably present a higher rate of local resorption in the long term. The region studied is limited to the radix. Being an observational study, it presents biases related to its elaboration such as selection or information, as well as the possible presence of confounding factors.

CONCLUSION

The study demonstrated that free minced cartilage can be used in the radix region with satisfactory results, presenting a low rate of visual perception when compared to tactile perception, without negatively influencing the satisfaction of the result.

REFERENCES

1. Gordon SD, Warren RF. Autogenous Diced Cartilage Transplants to Bone: An Experimental Study. Ann Surg. 1947;125(2):237-40.

2. Peer LA. Diced cartilage grafts. Arch Otolaryngol. 1943;38(2):156-65.

3. Erol OO. The Turkish delight: a pliable graft for rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;105(6):2229-41.

4. Erol ÖO. Chopped cartilage graft wrapped with Surgicel in nose surgery (plasticine-like graft). In: Third European Association of Plastic Surgeons (EURAPS) Meeting; 1992 May 14-16; Pisa, Italy.

5. Erol ÖO. Chopped Cartilage Graft Wrapped with Surgicel in Nose Surgery (Plasticine-like Graft). In: 11th Biennal Congress of the International Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgery. 1992 Feb 29-Mar 4; Guadalajara, Mexico.

6. Guerrerosantos J, Trabanino C, Guerrerosantos F. Multifragmented cartilage wrapped with fascia in augmentation rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;117(3):804-12. DOI: 10.1097/01.prs.0000200068.73092.5d

7. Daniel RK, Calvert JW. Diced cartilage grafts in rhinoplasty surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;113(7):2156-71.

8. Guerrerosantos J. Temporoparietal free fascia grafts in rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1984;74(4):465-75.

9. Elahi MM, Jackson IT, Moreira-Gonzalez A, Yamini D Nasal augmentation with Surgicel-wrapped diced cartilage: a review of 67 consecutive cases. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;111(3):1309-18.

10. Daniel RK. Diced cartilage grafts in rhinoplasty surgery: current techniques and applications. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;122(6):1883-91.

11. Daniel RK. The role of diced cartilage grafts in rhinoplasty. Aesthet Surg J. 2006;26(2):209-13.

12. Vidal MA, Kokiso D, Vidal BP, Andrade Filho AML. Cartilagem fragmentada para aumento do radix nasal. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2015;30(1):2-7.

13. Taş S. Ultra Diced Cartilage Graft in Rhinoplasty: A Fine Tool. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2021;147(4):600e-6e. DOI: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000007794

14. Kreutzer C, Hoehne J, Gubisch W, Rezaeian F, Haack S. Free Diced Cartilage: A New Application of Diced Cartilage Grafts in Primary and Secondary Rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;140(3):461-70. DOI: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000003622

15. McKinney P, Sweis I. A clinical definition of an ideal nasal radix. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;109(4):1416-8; discussion 1419-20. DOI: 10.1097/00006534-200204010-00033

16. Simms GF, Irwin RC. Diced heomologous cartilage in hernioplasty. J Med Soc N J. 1952;49(9):406-7.

17. Brodkin HA, Peer LA. Diced cartilage for chest wall defects. J Thorac Surg. 1954;28(1):97-102.

18. Erdelyi R. Diced cartilage in plastic surgery. Acta Chir Orthop Traumatol Cech. 1960;27:521-8.

19. Limberg AA Jr. The use of diced cartilage by injection with a needle. 1. Clinical investigations. Plast Reconstr Surg Transplant Bull. 1961;28:523-36.

20. Lemperg R. Studies of autologous diced costal cartilage transplant. II. With special regard to morphological changes and 35S-sulphate uptake in vitro after transplantation to the hip joint. Acta Soc Med Ups. 1967;72(3):141-72.

21. Erol OO. Long-Term Results and Refinement of the Turkish Delight Technique for Primary and Secondary Rhinoplasty: 25 Years of Experience. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016;137(2):423-37. DOI: 10.1097/01.prs.0000475755.71333.bf

22. Souza GMC, Costa SM, Penna WCNB. Enxerto de cartilagem picada injetável para rinoplastia: método e experiência do Hospital Felício Rocho. Rev Bras Cir Craniomaxilofac. 2012;15(1):17-20.

23. Ma JG, Wang KM, Zhao XH, Cai L, Li X. Diced Costal Cartilage for Augmentation Rhinoplasty. Chin Med J (Engl). 2015;128(19):2679-81.

1. CRER - Centro Estadual de Reabilitação e Readaptação, Goiânia, GO, Brazil

2. Instituto Arruda Cirurgia Plástica, Goiânia, GO, Brazil

Corresponding author: Fabiano Calixto Fortes Arruda Rua T50 n 723 Setor Bueno Goiânia, GO, Brazil, Zip Code: 74215-200, E-mail: arrudafabiano@hotmail.com

Article received: April 4, 2023.

Article accepted: December 5, 2023.

Conflicts of interest: none.

Read in Portuguese

Read in Portuguese

Read in English

Read in English

PDF PT

PDF PT

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to Cite

How to Cite

Mendeley

Mendeley

Pocket

Pocket

Twitter

Twitter